In a career spanning more than three decades, writer-director Bernard Rose has had the good fortune of developing films and telling stories that hold a deeply personal attachment for him. From his Beethoven film, IMMORTAL BELOVED, to his numerous adaptations of the works of Leo Tolstoy, to one of my favorite horror films, CANDYMAN, he has embraced the opportunity to tell the stories and explore the lives and works of some history's most creative minds, as well as some of his heroes (Candyman notwithstanding, of course).

This weekend, American Cinematheque is hosting a retrospective of Rose's work, which will include screenings of PAPERHOUSE, IMMORTAL BELOVED, MR. NICE, IVANSXTC, THE KREUTZER SONATA, BOXING DAY, CANDYMAN, and a sneak peek of his latest film, an adaptation of Mary Shelley's FRANKENSTEIN.

I had to opportunity to speak with the director and discuss his storied and varied career in advance of the event.

Horrorella: Congratulations on the upcoming retrospective - it sounds like a great program and opportunity for fans to be able to take in some of your films.

Bernard: For me, it's especially nice to be able to show the three Tolstoy films together because they were kind of conceived as a sort of trilogy. And during the course of the films, you actually see Danny Huston age like 11 years.

Horrorella: When they were conceived, did you intend for Danny to be starring in all of them, or was that just the way it fell together?

Bernard: It's kind of what happened, but I think one of the interesting things about the way Tolstoy writes is that the central character is always a version of Tolstoy. So there's a kind of commonality about different characters in different Tolstoy stories that's actually kind of a fun thing to do to have the same actor play them all in the different novellas, you know?

Horrorella: It seems like it would be a great way to bring a synchronicity to the series. How did the project hit its genesis and where did it come from?

Bernard: The first time I really came into contact with Tolstoy was when I was researching my Beethoven movie, IMMORTAL BELOVED. I had actually read the story "The Kreutzer Sonata" mostly because, you know, it had the title of a Beethoven piece of music in it and I was curious to see what Tolstoy thought of Beethoven. And there was this very funny description of the effect of music on people's emotions in "The Kreutzer Sonata", which I ended up stealing and putting into Beethoven's mouth in the scene where he hears The Kreutzer Sonata in IMMORTAL BELOVED. It's is actaully this thing where Tolstoy talks about how if you hear a marching band, you march, if you hear a Mass, you take Communion, if you hear a waltz, you waltz. So what emotion is he supposed to have when he's listening to The Kreutzer Sonata? And he's very disturbed by it. And of course, Tolstoy's answer to the emotion he's interpreting Beethoven is intending in The Kreutzer Sonata is a sexual thing. Which, of course, it is. And that's the basis of the novella.

But I think that Tolstoy's point is that the emotions that are in Beethoven aren't off the mark. I think that a lot of the emotions in music are sexual anyway. There's always been this whole thing about rock and roll and this whole thing about dancing and this whole combination of music and sex are all all very closely intertwined, i think, and he was sort of freaked out by that. And obviously people have been over the years.

I was interested in Tolstoy as an author, and I thought there was something really powerful and interesting in the way he writes - it's so visceral. And after that, I read ANNA KARENINA, which is of course, his most famous book, and decided to make an adaptation of it, which I did. I went to Russia to do that film for Warner Bros. in the nineties, and during the preproduction of that movie, we were in Moscow, and I asked if I could go to Tolstoy's farm, which is about 300 kilometers south of Moscow. In the nineties, you could never just travel freely around Russia. But the people that I was with had high-level contacts so we were able to go.

So they took me - and you realize why they don't give you permission to travel more than 300 kilometers outside of Moscow - there's a freeway, basically, like any freeway anywhere, but then when it gets to 300 kilometers from the city, the road disappears. Literally. There's no road suddenly. It's just forest. It suddenly becomes very very wild. Very remote.

So I was at the farm and we looked around the house and it was quite wonderful and this guy was at the house and asked, "Do you want to visit Tolstoy's grave?" So I sad, "yes, sure." And instead of just saying "It's back there" or "it's behind the house" - Tolstoy wasn't buried in the graveyard because he had pissed off the Orthodox Church so much - he gave me a map. And it was a couple of miles walk to it. So I went on my own. And you'd walk up this path and through this wood, and on the back of the map, they had printed the passage from WAR AND PEACE where Pierre walks through the wood and has a sort of spiritual experience through the wood. And you look at it, and you realize, this is exactly where Tolstoy used to walk in the woods.

Horrorella: Cool!

Bernard: And you go there and you come - this is where it gets really cool - you come to the middle of this clearing in the woods, right? And it's this beautiful, Russian silver birch wood, and you're in the middle of this clearing and the floor of the forest is all kind of mossy and green and it's almost like somebody has cut a little circle out of the trees there and you think, "wait a minute...where's the grave?" and you realize there's no grave. And in the middle of this clearing in the woods, there's a slight kind of mound in the ground. That's it. That's where Tolstoy's buried. And you know, I went there, and I was completely on my own. It was very scary.

Horrorella: It sounds beautiful at the same time though - just an incredible experience.

Bernard: It was. It was wonderful, actually.

I think although there were all sorts of good things about the experience of doing ANNA KARENINA that came out about it, in the end my feeling about the movie as it was finally completed was that it was it was profoundly and fundamentally a failure in the same way that all the versions of Anna Karenina are a failure, because the problem is that they always start off fine - when she's starting the affair with Vronsky and she's leaving her husband - that's fine, but that whole crisis point with her being in trouble with society...all that, you're only half way through the book. The book goes on for hundreds of pages after that, which people always end up cutting or getting bogged down in in film adaptations and missing the point of the book.

It ends up being a film about a woman who kills herself because she's jilted in love, when that's not Tolstoy's point at all. Tolstoy's making a much much bigger point in the novel which is that she kills herself because she made this man into her god, as it were, as opposed to finding it within herself. It's actually a very modern and profound idea that's in the book, and that really didn't work in my adaptation, which also really got butchered in the editing too.

Horrorella: On that subject, since you've worked so frequently in adaptations, how do you try to go through that process and remain true to the source material, while also still making either any necessary changes or any changes that will put your mark on the story? What's the balancing act to that?

Bernard: I think it's very very hard. And it gets harder when you deal with a novel as good as Anna Karenina. Obviously, all novels are hard, but that one is harder than most. There were all sorts of problems in trying to make it as a commercial movie, but I think there was a fundamental thing that was wrong with the project and the movie and all movies of Anna Karenina - it's that they're just too short. Even when the film was longer - it had a lot of footage cut out of it - it really should have been 10-15 hours minimum, I think, to actually capture what's in the novel. Which, of course, you could have done as a large scale TV show, you know, and it has been done that way. But I felt very dissatisfied with the whole thing at the end of it.

Another problem is if you recreate 19th century Russia and shoot it where we did, it's all so visually overwhelming that that's what you end up seeing, you know? And the whole point about Tolstoy is the interior life of his characters and their emotional directness and I thought, really, the way to do this properly, would be to get rid of all the studio trappings, number one. Number two, to basically take much shorter works so you didn't have to cut stuff and so you could even expand it where you need it to, rather than compress it.

And that's what I did with IVANSXTC - setting it in Los Angeles rather than setting it in Russia and getting rid of all the value stuff of a large scale movie and getting rid of all the stuff that I felt was actually a barrier to understanding what Tolstoy was trying to say.

So that was the idea behind doing IVANSXTC and that worked much better and I carried on and then I went back to THE KREUTZER SONATA, which is what got me involved in Tolstoy in the first place. And then I did BOXING DAY, which I think is, in some ways, my favorite of all my films.

Horrorella: How so? Why is that one your favorite?

Bernard: It's based on the story "Master and Man " It's about a guy who is going to buy a wood and he's in a hurry to conclude the deal over Christmas, and he heads off with his servant in a sleigh into the forest and they get stuck and they have to survive. And it's all about which one of them is going to make it and one of them is this patrician, arrogant guy, and the other is this little serf. And I did it with a guy a and his driver in a limousine. They get stuck in Colorado, in the mountains and they lose their GPS signal and they can't get help an they have to spend the night in the car and it's actually a really good movie.

Horrorella: Music has always played a pivotal role in your films. From having the very memorable, beautiful scores by Philip Glass or being the focus of the films like in IMMORTAL BELOVED and THE DEVIL'S VIOLINIST. Where does that attraction come from and how do you feel that music fits into both the stories and the production of your films?

Bernard: I'm a musician myself - I'm a classical pianist. I've always been very involved with music, and actually I started my career in the music business. I made music videos in the early 80's. I did them for UB40 and Frankie Goes to Hollywood and all that. And that was sort of how I started my career as a filmmaker was doing that stuff.

I've always been involved in music of different kinds and it has always been really important to me, and that's why I wanted to make a film about Beethoven. Beethoven's Sonatas are such an important kind of literature of piano music. The incredible kind of sweeping, novelistic work - I still play them a lot and get a lot out of them. And every time you play them, you find something new.

When you have a composer like Beethoven, obviously, he's never been obscure. He's always been one of the top composers of all time. But people also have a slightly stodgy impression of him. He's a bust on a piano - it's not like he's a real human being.

And Beethoven's always been such an awkward figure. When you read about him - even in the 19th century, they always tried to make their heroes, any artist, heroic and romantic. It was hard with Beethoven, because he was an awkward fucker, you know? He was deaf and he was angry and he was bad-tempered - nobody really liked him.

It's what makes him an interesting subject for a film. And I was always a huge fan as a kid of the films that Ken Russell made about composers. I think they were really inspiring. Particularly, I loved his film about Tchaikovsky, THE MUSIC LOVERS. It's a fantastic film. It reclaims Tchaikovsky as a serious music lover. People think of Tchaikovsky. as a guy who wrote a Christmas show, you know? But Tchaikovsky's symphonies are as serious as Beethoven's. There's as musically good. and he's probably the greatest orchestrator of all time, actually.

Horrorella: And it's also interesting to just dive into it from a historical perspective because when you get a figure as large as Beethoven, everyone just kind of recognizes him as a brilliant composer, and the majority of the populace just leaves it at that. So being able to flesh out his story into a very humanistic, understandable, relatable tale, it's something that kind of makes the story all the more special because the audience is able to relate to this giant legend.

Bernard: Yeah, and you know, I think the music is very relatable. And the reason we still listen to Beethoven is not because somebody tells us to, but because it's really powerful. I mean, if you go to any performance of the 9th Symphony, I defy you not to be moved. It's an experience. But you know, it's also an experience that demands a bit of concentration and work - Beethoven is not simple music. It's the epitome of the idea of a kind of elevated music that actually has a philosophical and emotional and spiritual content as a finer part from its pleasure capacity as tunes, you know?

Horrorella: Switching gears a little to your horror work - CANDYMAN is one of my very very favorite horror films. And one of the main reasons for that is that it takes the concept of a very traditionally-structured legend and plunks it down in the middle of a very modern, very urban setting. And it's a thread that Clive Barker loosely included in the original work, but how did you decide to develop it the way you did and bring that front and center and make it the core of the film?

Bernard: Well, Clive's story was set in Liverpool. And I decided early on when I was developing it that the film would be much better done in the U.S. And I went to Chicago on a research trip to see where it could be done and I was shown around by some people from the Illinois Film Commission and they took me to Cabrini Green, which was the housing project in the movie. And I spent some time there and I realized that this was an incredible arena for a horror movie because it was a place of such palpable fear. And rule number one when you're making a horror movie is set it somewhere frightening. And the fear of the urban housing project, it seemed to me, was actually totally irrational because you couldn't really be in that much danger. Yes, there was crime there, but people were actually afraid of driving past it. And there was such an aura of fear around the place and I thought that was really something interesting to look into because it's sort of a kind of fear that's at the heart of modern cities. And obviously, it's racially motivated, but more than that - it's poverty motivated.

Horrorella: Did you find it fearful or threatening yourself while you were there?

Bernard: Yes it was, but I also met people who lived there. The first time I went there, I went there with the people from the Film Commission, and we had cops there and things like that. But I actually met some people who lived there and went back later, and when I went back, I thought, yeah, you could definitely get in trouble there but honestly, most likely not, unless you went looking for it, you know? And that to some degree, the fear was exaggerated. And the reasons for that were interesting.

That's one of the things I love about the horror genre. I love that it's a vehicle for people's anxieties. It's a very interesting view into what's going on. I know the whole thing about NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD is sort of reflecting the Vietnam War. We've had a lot of of interesting zombie movies - whenever there's war, people are interested in zombie movies because it's like a kind of retribution. And you know, the anxieties of society are very apparent in what they choose for their horror films.

Horrorella: Yeah. And I think it's fascinating to review horror films throughout the decades and to see how it reflected culture at that time - from the Vietnam era to the post-9/11 era with Eli Roth's HOSTILE films and the way they highlight America's xenophobia at that time. It's fascinating to see collectively how a populace's fears can be exhibited through the art that they are making.

Bernard: It is. And I think that's why horror films have a tendency to last much better than other genres because we still watch THE EXORCIST. Not just academically - people watch it for the same reason they watched it back in 1973 - they watch it to get frightened.

And I also think that one of the things about horror films is that everyone forgets is that if you actually frighten somebody with something supernatural - my definition of a horror film is strictly that t has to have a supernatural element. To me, SILENCE OF THE LAMBS is not a horror film. It's a police procedural thriller. But a horror film has to have a supernatural element and if you make someone afraid of something supernatural, you essentially make them believe it and in that sense, you're giving them a supernatural experience in a way that's more powerful than the one they can experience in real life. And that's especially true with a film like THE EXORCIST. It bolsters their belief systems in a weird way.

Horrorella: I've also found Candyman to be a particularly fascinating character because he's simultaneously terrifying and nightmarish - very very much a boogeyman, but at the same time, he's very alluring in a way. Can you talk a little bit about how you and Tony Todd worked to craft that character and to make him what was?

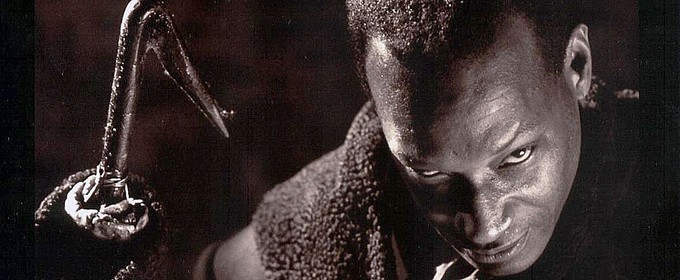

Bernard: The idea always was that he was kind of a romantic figure. And again, romantic in sort of the Edgar Allen Poe sense - it's the romance of death. He's a ghost, and he's also the resurrection of something that is kind of unspoken or unspeakable in American history, which is slavery, as well. So he's kind of come back and he's haunting what is the new version of the racial segregation in Chicago.

And I think there's also something very seductive and very sweet and very romantic about him, and that's what makes him interesting. In the same way there is about Dracula. In the end, the Boogeyman is someone you want to surrender to. You're not just afraid of. There's a certain kind of joy in his seduction. And Tony was always so romantic. Tony ties him in so elegantly and is such a gentleman. He was wonderful.

Horrorella: He adds this great sense of refinement to him while scaring the crap out of you. There's kind of this push-pull of being drawn to him and simultaneously finding him terrifying.

So would you ever have an interest in directing horror again?

Bernard: Well, I did a Frankenstein film too, which I'm actual very proud of. And it's actually an unusual take on the Mary Shelley book. It's set in contemporary Los Angeles. And I had never actually read the Mary Helley book before, and when I did, two things really impressed me. One is that how modern it still feels. Unlike a lot of science fiction - because it is a scifi book, as well as a horror book - a lot of science fiction becomes dated because the real technology overtakes it, but at the very beginning of industrialization and science, she intuited that the aim of science would be to create artificial life. That's still our goal and it's very much where people are headed now. In 200 years, people haven't achieved it, and that's why her book is still relevant.

And the other thing I loved about the book that I've never seen portrayed in any version of the story was that the monster educates himself and he sounds like Lord Byron, basically. He's very educated and he's upset that the way he's being treated because he feels like he has this delicate, refined, romantic spirit, and he's treated like shit because he's a sub-human. So I wanted to make a film from the monster's point of view. So in the film, he just wakes up in the laboratory and doesn't know who he is or how he got there or what happened to him. He's a perfect creature. And he's been made in a 3D printer. He's been created - he's not been made out of body parts.

Mary Shelley never said the monster was reanimated body parts. She said that Frankenstein made him and she wasn't going to tell you how he did it. That's the 1930's film that came up with that idea. But nowadays, the idea of 3D printing flesh is not only possible, but is something that people are actually doing. So I thought it was a good way to achieve it. So he just wakes up and he's this perfect creature and he doesn't know how to speak or eat do anything or look after himself. And it's about his short and unpleasant life.

And inside his head, he has a monologue which comes out of the novel which is directly from the book which is where he sounds like Lord Byron. So he has this internal monologue that is very educated in a very subtle way, but he can't speak and he has to learn to speak over the course of the film. He can't express himself. I thought that was an interesting dynamic to play with.

He wakes up and he's beautiful and he's perfect. And then of course, after a while, they haven't done him correctly and he starts to get covered inside and out with cancers and growths and hideous things and he becomes very unpleasant looking . And that point, they don't like him anymore and they don't want him there anymore and they're looking to get rid of him and start again. But of course, he's alive and he's conscious and he doesn't really want to die.

Horrorella: This sounds awesome! I am so excited to see this!

Bernard: And I'm writing another horror movie right now, actually. I'm kind of into the horror genre at the moment. There's still an audience for horror films. There's not an audience for just about anything, but there is always an audience for horror movies, you know?

Horrorella: Horror movies stay strong through any period - we are always hungry for them. I hope your new project is going well.

FRANKENSTEIN will hit the festival circuit this fall, and is set for a theatrical in early 2016. In the meantime, if you're in LA this weekend, check out the Bernard Rose Tribute, Beauty and Thorns, at the Aero Theater. It will include screenings of FRANKENSTEIN, PAPERHOUSE, the Tolstoy trilogy, IMMORTAL BELOVED, conversations with Rose himself, and the opportunity to be Candyman's victim as he seduces you on the big screen. An exquisite program for every lover of music, literature, horror and film.