"I'm sorry, it's just a bit distracting trying to talk to your stepmother with her bush staring you right in the face."

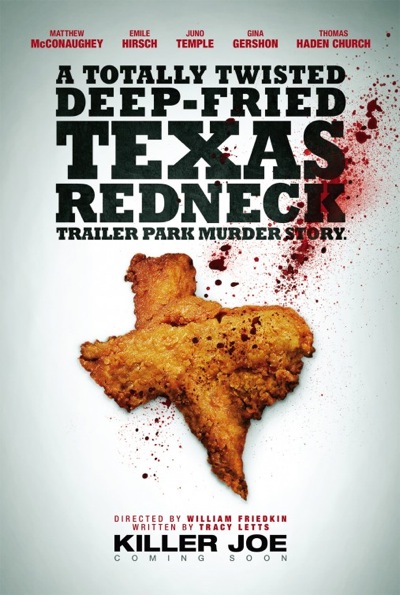

Welcome to the deliciously twisted Texas of Tracy Letts's KILLER JOE. It's a savage, scuzzy world in which a dysfunctional, drugged-out family warily comes together for the purpose of a financially-beneficial murder (of another family member, natch). We've seen lowlifes of this variety before, but never have they torn into each other with such poetic invective. It's an unholy union of Tennessee Williams, Harold Pinter and Sam Shepard - nasty, malevolent, and funny as hell. It's Tracy Letts. And it fits William Friedkin like a black, bloodstained leather glove.

This duo first hooked up for 2006's magnificently disturbing BUG, which seemed to reawaken the terrorist in Friedkin. It was his most viscerally shocking film since CRUISING, and possibly his most controlled work since THE EXORCIST. With KILLER JOE, Friedkin gets to indulge his taste for black comedy while directing a talented ensemble of actors who are acutely aware that these types of roles are unlikely to pass their way again. As the titular contract man, Matthew McConaughey spikes his natural charisma with a double shot of strychnine; while you're helplessly drawn to Joe's calm facility for murder, you're relieved he's on the other side of the TV screen. Meanwhile, Gina Gershon imbues her bitch-on-wheels persona with a pathetic desperation that makes her pitiable if not quite sympathetic. Everyone is game, and they've all pitched their performances at a level that would make Edward Albee's ears bleed.

Though this is quintessential Friedkin, he happily shares the credit (or blame) with Letts. And now that the completely uncut version of the film is coming to Blu-ray and DVD on December 21st, he can take comfort in knowing that their collaborative vision is no longer in danger of being compromised. I had the great pleasure of chatting with Friedkin the other day, and he was as candid as ever when it came to the subject of the MPAA. We also talked about his personal connection to Letts's work, the status of a potential SORCERER restoration, and the randy glory of Clarence Carter's "Strokin'". Here goes...

Mr. Beaks: I love that your film opens with "William Friedkin's Film of Tracy Letts' KILLER JOE."

William Friedkin: He didn't have that contractually, but I decided to give that to him because I think it's accurate and it's earned. I didn't create it, he did. Whenever possible, the producers and studios don't really care about that, in part it's because they don't want to set a precedent so that other writers ask for it. I also think there's not a lot of appreciation, or not as much as there should be, for writers. I started my career in films working with people like Harold Pinter, and it's kind of a direct line from Pinter to Letts in my work. I think he's as good as there is today.

Beaks: I think there's a precedent-shattering quality to Pinter's work as well as Letts's. I think they shake up convention in interesting ways. With Tracy, there's a touch of Tennessee Williams in there, but also something modern.

Friedkin: It's his own voice. It's based on his own experiences and deep feelings that he certainly had when he started to write plays in 1990. He was twenty-five years old, and I don't know if he still feels the same way. AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY was not as angry or as edgy as some of his earlier work like KILLER JOE. To me, BUG is an absolute masterpiece of dealing with the paranoia that exists in the world today. It certainly started before Tracy wrote BUG, but I think he captured it totally. I read the script again recently. It's just brilliant.

Beaks: KILLER JOE has a young man's rage lurking within it. What did you connect with when you first read KILLER JOE?

Friedkin: I believed it. I haven't done that many films, but the ones I've done and the ones that are particularly close to me are the ones whose values and ideas I share. I haven't read any dramatist today in any language who has the same facility to capture a large chunk of the zeitgeist that Tracy has. I connect with everything in it. I understand it. I understand the obsession, the need to control, the need for vengeance, punishment... all of that stuff is so rampant in our society. And Tracy does it largely in a realistic way. That's not going to catch on with a wider public. If there is a kind of competition between films of fantasy and films of reality, fantasy wins hands down. Tracy's work is much appreciated of course, but people prefer fantasy - even in terms of the depiction of violence. That's understandable to me. Most people just go to see a movie or a play to be entertained, not to be reminded of social conditions. What Tracy does is very brave, but it's what every good writer has to do, and that's follow his own voice.

Beaks: You said there's a certain audience for this kind of film. Do you think there was perhaps more of an appetite for this kind of material in the '70s.

Friedkin: I don't remember anything quite like this. In terms of hard-edged films, nothing I know of that came out of the mainstream of America was as hard-edged or tough as THE EXORCIST. It would be very difficult to make something like that today. But it thrived, of course, from the '70s right through to today. There's still a large audience for THE EXORCIST in all media, but there weren't a lot of things like that. A lot of people talk about the '70s as a golden age of filmmaking, but that involved only a handful of films really. By and large, the studios were still making Broadway musicals and large costume dramas. MARY, QUEEN OF SCOTS; NICHOLAS AND ALEXANDRA; DOCTOR DOLITTLE; FIDDLER ON THE ROOF... three of those films were nominated for Best Picture with THE FRENCH CONNECTION. The so-called '70s revolution was very short-lived. It was like fireworks. There were a handful of filmmakers in America who had been influenced by the French New Wave and the Italian Neorealists, and we were trying out these ideas here. It's now written about, as you probably know, as a kind of golden era in American filmmaking. Those of us who were involved in it and making films in that period, I don't know if we think of it as a golden era. I can tell you that the guys who ran the studios then and controlled production and budgets, they knew what they were doing. You never had these runaway budgets like you have now. There were guys at the studios who knew what they were doing, and that's certainly changed. But I don't remember a film that was as in-your-face as THE EXORCIST. It was much more challenging to audiences' taste than KILLER JOE, and it didn't receive an NC-17. It got an automatic R with no cuts. I never had to cut a frame for the rating. There has never been a more liberal ratings board since then. But a major studio will never get an NC-17 because they control the ratings board.

Beaks: Going up against the ratings board with KILLER JOE, what in particular did they object to?

Friedkin: Everything!

Beaks: (Laughs) Everything?

Friedkin: Yes! That's a quote from Tracy. I wasn't there. I didn't appear before the board for the appeal, but Tracy did along with David Dinerstein, who was the distributor. I was in Vienna directing an opera, but I wouldn't have gone if I was available. I wouldn't have gone to the appeal. But Tracy went, and it went along these lines: the ratings appeal board is made up mostly of exhibitors. There were thirteen of them. And Tracy said what bothered them was the personalization of violence. He said, "What do you mean? Can you explain that?" And one of the guys said, "Take SAW for example. If a whole bunch of people get killed in SAW, it's impersonal. It's sort of fantasy." And Tracy said, "You mean because the actors did their jobs well, and we did our jobs well and we made it personal, you're going to give us an NC-17?" And they said, "Yeah, that's about right." So Tracy said, "In other words, if it had been cartoon violence instead of realistic violence, it wouldn't have bothered you at all?" And they said, "That's right." He then wrote to me and said it was very clear from the moment he entered the room that they were dead set against letting the film get an R with any cuts. Their minds had been made up, and they came back thirteen-to-zero after twenty minutes. I don't know what took them so long. I at one time thought the ratings board was necessary to give guidance to parents about what their children should or should not be seeing, but it's evolved into something a lot more draconian than that. It's now a censorship board. The only other place in the world that did anything like this with KILLER JOE was Germany of all places. Not England, France, South America... it's played all over the world... but the German censors were very specific with what they wanted cut, which was virtually everything. They wanted it cut, not trimmed. And I wrote to the German distributor saying, "If you do this, I will publicly denounce the film in Germany, take my name off of it, and accuse you of book burning - the same thing that happened in Germany sixty years ago. So they severely restricted its release. But I found it ironic that Germany is the only country in addition to America that wanted to censor the picture. And it was only a series of events that caused the distributor to not insist that I do it. They took the film out and played it publicly and for critics in Venice, Toronto, Seattle, Paramus... a whole bunch of other places. The reviews were great, the audience reaction was everything they could've wanted, and then they submitted it for a rating, and came this NC-17. To pull back then would have invited outrage among those critics who wrote about the film and what its content was.

Beaks: They certainly would've lobbied for the film. But it's as Tracy said: it's always the films that do their jobs too well that get targeted.

Friedkin: Not only that, but independent films. They will never do that to a studio film. Under the dark of night, they will make little frame cuts or little adjustments or fog out something that is a kind of a nod to the power of the ratings board. That will get some of the most violent or even sexually disturbing movies ever an R - like THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO, which shows graphic anal rape and the vengeance scene, which is much more disturbing than anything in KILLER JOE.

Beaks: There's often something comedic to the violence in KILLER JOE. I never thought I'd see a vicious beating administered to Clarence Carter's "Strokin'". That really threw me, but it was wonderful. Why use that song?

Friedkin: (Laughs) I just liked it. It is a kind of well-known song in the so-called "redneck world". It's appreciated for its farcical nature and its double entendre, which is very clear. You hear it in jukeboxes all over the area where this film takes place. I think it's great. It's a funny, great song, and very courageous on the part of Clarence Carter to write and perform it. And I don't think he or his family sees it as down-and-dirty; I think they see it as humorous. I talked to Clarence Carter's wife, and she said, "You know why I call him CC instead of Clarence Carter?" I said, "Because that's his initials?" And she said, "No, I call him CC because he's in charge of climax control." She sees it as very funny. I see it as funny. I don't see it as misogynistic or as a challenge to the other gender or anything like that. I see it as very humorous and reflective of the attitudes of a lot of people. I love the song!

Beaks: So do I!

Friedkin: I didn't plan to use it, nor did Tracy. Somebody brought it to me as part of a group of songs. I don't know how that even got into the group! It was the '80s when it came out, and I'd forgotten all about it, how every time I'd listen to it I'd crack up.

Beaks: I thought it was interesting that you chose to work with [director of photography] Caleb Deschanel on this.

Friedkin: He and I have been good friends for a while. We worked together on THE HUNTED, and I went to him with this simply because I so admire his work and like him personally. I never thought he'd do it because he still does a lot of high-profile films, big studio films. He did the JACK REACHER film that's coming out this week, and he's shooting something now in New York. He also has a thriving commercial business. But we were having dinner, and I talked to him, and I said, "Let me send you this script. See if you like it." I said, "Here's how we're going to do it: very low budget, very down-and-dirty, we've got to shoot digital, not film." He read the script and loved it. He said, "Look, I haven't worked this way for forty years. I haven't tried to make a film in twenty-five days for forty years. I think it would be a great challenge." So he put aside other commitments and did it. He's great to work with. He's a major talent. You look at the film and it doesn't look like video. It's well lit. And if films shooting on digital equipment are well lit, they'll look great. And everything is going to be shot in that format. It's all over for film. He knows that, and so do I. Eastman Kodak is shut down, or they're only doing video now. And Fuji? Nobody's making 35mm stock. So the only thing left in 35 will be prints that have survived - and even most of the film societies that I'm aware of are converting. The Cinefamily group here is converting to digital.

Beaks: They have to.

Friedkin: They must, or they'll never get a print.

Beaks: Quentin Tarantino owns the New Beverly, and he is steadfast in his refusal to go digital.

Friedkin: Well, he can say that, but there's no more film for him to run. I would rather see a digital video than a lousy, faded, scratched-up print that's spliced and with sound blips and all of that stuff. I would definitely rather see a clean print with good sound. And a lot of the classic films have been converted. You know who the great opera singer Caruso was, right?

Beaks: Yes.

Friedkin: Whenever they recorded him after the turn of the century, the equipment was horrible. If you listen to a Caruso recording today, it's all needle scratch. And buried inside the scratch and the noise is Caruso's voice. Well, now they have a way to go in and clean all that other crap out to some extent, to remaster it and bring it back the way it was meant to be heard, but there wasn't the technical facility to do it. I would much rather hear that sort of remastered version of a great voice than listen to needle scratch. That's how I regard the digital world.

Beaks: You're fine with the quality of the image you get when it's projected?

Friedkin: Absolutely. It's flawless. A lot of people think that when I shot a film like THE FRENCH CONNECTION that I went out and put scratches on it and dirt and splices and all kinds of crap, because that's the way they saw it in the theater. It was never intended that way. The Blu-ray of THE FRENCH CONNECTION now is pretty much precisely what I saw when I looked through the viewfinder of the camera.

Beaks: When it first came out [on Blu], it didn't look right.

Friedkin: That was the mass production. We found that and corrected it. The master that we made was perfect, and then it went to four different companies. They produce a glass disc after you make the video master, then there's another stage, and then there's the mass printed stage. There are four stages done by four different companies, and they fucked up! When Owen Roizman and I looked at the master, it was perfection! And then we bought some copies from Best Buy, and they were awful. The guy at Fox, this guy named Schawn Belston, who was in charge of this... we started to root it out, and they figured out that along the line the specs were changed without any of our supervision.

Beaks: I've talked to other directors about this, and I've often heard that if you don't sit with them and go frame by frame, they'll make changes without your approval.

Friedkin: That's true, but there are also changes in the formats that you can't track until the release version comes out. You can't track the mass printing, just as we couldn't track mass printing of a 35. I had total control of all the prints in the initial run of THE EXORCIST. There were only twenty-six theaters where THE EXORCIST opened. I had three editors with me, and we approved every single print that went out for the twenty-six-theater initial screenings. I went to all the theaters with technicians from Warner Bros. We set the light level on the screens, we set the sound level on the speakers, and I would call the projectionist every night of the six-month run and make sure everything was okay. And they would tell me things like, "Mr. Friedkin, we had a scratch in reel seven." Or "Reel four broke while we were running it." And I'd call Warner Bros and get them a new reel four or a new reel seven. I had complete control of that! But the minute you release a film on a few thousand screens, that's impossible - except now with digital video. Look at CITIZEN KANE. The Warner Bros digital CITIZEN KANE is magnificent. They've cleaned out scratches that I've seen every time. I know where all the scratches are on the 35 prints of CITIZEN KANE, and they've cleaned all of that out. And it now looks, I'm sure, as Welles and Gregg Toland intended. It's sheer perfection. It's wonderful.

Beaks: Speaking of restoring films, what's the status of SORCERER?

Friedkin: I have a meeting with Universal today at 2:30 to see if they're willing to do something. Paramount, it turns out, is out of it; they had only a twenty-five-year lease, which is expired. So all of the television and home video rights are with Universal, and I'm now having a personal meeting with them, because Warner Bros wants to sublease it or do whatever - buy it and put it out. So now I'm going in to talk to the head of Universal Home Video and see what he'll do, if anything. And if nothing, I have only the legal option.

Beaks: Are you hopeful?

Friedkin: I'm always hopeful. Sure.

Beaks: How much work would have to be done in terms of restoring it?

Friedkin: Quite a bit. There are no great prints out there. There is one print that Paramount made at the end of 2011 or the beginning of 2012 that was run at [the American Cinematheque's Aero Theatre], and we're trying to track down where that is.

Beaks: I would love to have a great copy of that film.

Friedkin: So would I! And that's what I'm trying to do. It's been a step-by-step process largely because the legal department as well as other departments of the studios have been so decimated that they don't have personnel that can dedicate the time to figure out where all of this stuff is. It's all been put in off-shore companies that are now nothing more than a guy at a desk in a little room. It takes quite a bit of time and effort to track it all down.

Beaks: I wish you the best of luck on that.

Friedkin: Thanks a lot, Jeremy.

Beaks: One final question: is there a specific film of yours that you feel is perhaps not appreciated as it should be?

Friedkin: Oh, I don't think in those terms at all. I'm not even aware of that. I'm aware of the films that made more money than other films, but as far as appreciation? It's hard to say. I don't keep score. (Laughs)

Beaks: I was going to say RAMPAGE. I'm constantly recommending that to friends.

Friedkin: I appreciate it. Again, that falls into the category of realism, almost to a disturbing extent. That's had a tough road.

KILLER JOE hits Blu-ray and DVD on December 21st. The uncut version is currently available to buy and rent on iTunes - so do yourself a favor, and get yourself some first-class Friedkin this weekend. And be sure to share it with the family!

Faithfully submitted