Since making his feature filmmaking debut in 2005 with PRIDE AND PREJUDICE, Joe Wright has seemed acutely aware of Orson Welles's admonition that "anybody can make movies with a pair of scissors and a two-inch lens." In each of his films, he's executed at least one technically complex tracking shot - typically as a means of immersing his audience in a "foreign" land (e.g. The Netherfield Ball in PRIDE AND PREJUDICE, the beach at Dunkirk in ATONEMENT, and downtown Los Angeles's Skid Row in THE SOLOIST). But in his latest film, HANNA, Wright's obligatory single-shot flourish serves a more formal purpose: it's about demolishing an aesthetic. By staging a one-take brawl - between Eric Bana and four assassins in an underground train station - that allows you to clearly view every punch, feint and kick, Wright has reminded us that fight scenes can be every bit as fluid and breathtaking as an Astaire-Rodgers pas de deux. It's the badly-needed antidote to too many years of BOURNE-inspired shoot-for-the-edit sloppiness.

But there's much more to Wright than lengthy takes. Along with knowing how to let a shot play well beyond the point of blinking, the man possesses - in concert with Paul Thothill - a remarkably clean and kinetic editorial sensibility. In ATONEMENT, he timed passages of the film to the clickety-clack typewriter rhythm of Dario Marianelli's magnificent score; with HANNA, it's the throbbing music of The Chemical Brothers that drives the picture - and the action - forward. Wright is one of the few filmmakers I can think of who gets in the pocket like a drummer; you might even find your head bobbing to the editing beat as Saoirse Ronan cracks one skull after another. This movie grooves. And, again, the action is staged and cut with such precision, you always know what's going on.

With HANNA, Wright has proven he can break free of the prestige-picture racket and craft a straight-up crowd-pleaser anytime he likes - which seems a relief to him. In talking with the director a few weeks ago during the film's press junket, he expressed considerable distaste for the awards season "snake pit". Though there will likely be an awards push down the road for some aspects of his latest picture, he's quite happy that HANNA will, for now, be judged simply as a movie. He better enjoy it while he can: his next film - a Tom Stoppard-scripted adaptation of Leo Tolstoy's ANNA KARENINA starring Keira Knightley - will surely live and die on its potential to earn multiple Academy Award nominations.

Prior to the start of our interview, Wright, who was a little punchy from a long weekend of answering the same questions over and over again, decided to stretch out on a couch adjacent to the chair in which I was seated - thus creating a psychiatrist/patient tableau. It made us both laugh, so I decided to run with it before getting into the Q&A - which was far livelier than I expected. It's always a pleasure to chat with a filmmaker who genuinely loves making movies as much as we love watching them. Wright has it in him to be one of the greats before it's all said and faded to black.

Mr. Beaks: I suppose we should start with your mother. Or do you have something else on your mind?

Joe Wright: Breasts. My wife has recently had a child, and suddenly you realize that breasts are all about milk and bounty. They're not really for us. It's a rather sad revelation.

Beaks: It hasn't ruined breasts for you, has it?

Wright: Well, at the moment I can't really get close to them. (Laughs)

Beaks: How horrible.

Wright: They're so big and beautiful, and they're no longer mine.

Beaks: I'm sorry.

Wright: Thank you.

Beaks: So speaking of mothers... (Laughs) I'm attempting a clumsy segue into this wonderful film you've made. Obviously, you're a very specific filmmaker. The aesthetic is very clean. When I'm watching your movies, I feel like you know shot-for-shot how you want it to play. You strike me as a meticulous storyboarder as well. Is that how you work?

Wright: Generally, it is. But this one was a lot more improvised than the others. Because of certain budget and schedule constraints, and also geographical challenges, we had to think a lot more on our feet - which was really exciting, actually, and perhaps accessed a different part of my creativity. God, that sounds pretentious. "My creativity." Fucking hell! (Laughs) But I was interested in making a film that didn't really exist in the real world, but existed in a kind of dream space. Not a kind of CG Hollywood fantasy, but a kind of just slightly otherness. So it was working really from one's subconscious quite a lot, and coming up with ideas not knowing where they'd come from or why they'd appeared, but somehow if they worked within the poetic unity of the film then they might be interesting. It had a different feeling to the other films, and quite a liberating one.

Beaks: Music is always an integral component of your films. By having The Chemical Brothers involved early, was it perhaps even more of a driving force in HANNA?

Wright: Not "even more". The score for ATONEMENT, for instance, with the typewriter was definitely very much a part of the film from its conception, but I guess orchestral scores are far more divided from the rest of the film, the rest of the sound world of the film. Whereas the synthesized score we used in HANNA really sprang from the sounds that surround us every day, so there was no division between the sound effects and the music; they were kind of the same thing - music being the organization of sound. So The Chemical Brothers were working quite closely with the sound effects editor, and the sound effects editor would send The Chemical Brothers sounds, and they would incorporate those into the score. It was very much an open dialogue between the various departments in that respect in postproduction. But also a couple of the pieces had been recorded prior to shooting, so we were playing them as we were shooting.

Beaks: Okay. Because I was wondering if you'd timed out any of those sequences to preexisting music - in particular the underground fight scene.

Wright: Not to the exact piece of music, but certainly we were playing music while we were shooting it, so it had that kind of rhythm that we thought might be appropriate for that scene.

Beaks: I spoke to Eric earlier, and he said you shot that sequence at magic hour. Basically, you upped the degree of difficulty on what was already a very complicated shot.

Wright: But as with the beach shot in ATONEMENT, those shots are always done out of necessity. This scene, if it had been shot conventionally with different setups, would've required maybe forty different setups - and I usually only get fourteen in a day. I only had one day to do this sequence because of the budget, so it's a kind of all-or-nothing gamble. I'm not a casino man, but I do like to gamble on sets sometimes. And with that short window of shooting, you rehearse for seven hours and then have maybe a three- or four-hour window of shooting at the end of the day. And also it's about catching the light; it's about catching the magic hour.

Beaks: How many pages was that sequence?

Wright: I think that one was about two pages, but the action stuff wasn't really embellished in the script. It was kind of written in choreography.

Beaks: There's a strong emotional component to these tracking shots. Obviously, you're not just showing off. But there must be something... professionally gratifying about doing them.

Wright: I must admit I do really love the bravado of them. When you do one of those shots, everyone on set knows you're doing it that day, and it creates a different kind of atmosphere - a kind of heated, heightened atmosphere. Everyone is very tuned in, and adrenaline is high. So there's a kind of showtime about it. Do you know what I mean? There's a kind of theatrical excitement. It's almost like site-specific theater. That's kind of fun as well - especially towards the end of a shoot, when you're all kind of completely fucked. It gets the adrenaline going.

Beaks: Do you have any favorite tracking shots from other movies?

Wright: I AM CUBA. That shot that goes from the roof to the swimming pool. That is one of the most extraordinary shots I've seen in my life. Of course RUSSIAN ARK is an amazing thing. In fact, I met and worked with the steadicam operator [Tilman Büttner] who'd done RUSSIAN ARK on HANNA. He's an amazing operator.

Beaks: The operators who pull off these shots are rock stars in their own right. Like Larry McConkey, who's done some famous shots with Scorsese and De Palma.

Wright: They are. They have a certain swagger to them.

Beaks: (Laughs) Do you ever have to rein them in?

Wright: Of course! Everyone can get a bit full of themselves. Sometimes you've got to give them a slap. There's a whole kind of ridiculous hierarchy and ego. It's the same with makeup artists. You get your star wig-makers... they're these crazy characters. It's kind of funny.

Beaks: One of the things i find refreshing in discussing HANNA with my peers is that, this being March, we're not talking about awards. That discussion may come later, but, right now, it exists only as a film - whereas ATONEMENT and PRIDE AND PREJUDICE were thrust into awards season straightaway and viewed as racehorses. And you've no choice but to participate in that.

Wright: It's fucking horrible, actually. I was very green with PRIDE and ATONEMENT, and I genuinely believed that it was a meritocracy, and thought this was all kind of beautiful. I've wised up a bit subsequently, and tend to see it more for what it is. Tom Stoppard recently said that the purpose of awards is to honor the donor, not the recipient. I think that's very true. In the case of the Oscars, the donor is obviously the studio and the industry itself. It's a strange thing. And it's nice to make a film that exists outside of that arena. Unfortunately, if you make a drama - especially a period film - it is immediately forced into that snake pit.

Beaks: So was making this film a way of breaking out of that cycle?

Wright: It was incredibly liberating creatively.

Beaks: More fun than the others?

Wright: I wouldn't say more fun than the others, but I really wanted to smash everything up. I wanted to break down all of my conditioning I'd had over the past few years, and just do something a bit more punk. It was a lovely freedom - which is also terrifying. I was really scared during the making of it that I was doing something that could possibly end my career. And one doesn't ever want to do that, because I love making films and it's all I can do. I did try furniture restoration for a while, which I kind of liked, but the fumes really get to you. Fuck, I'm rambling, aren't I?

Beaks: (Laughing) No, this is good.

Wright: (Laughs) You know what I mean. It was nice to be a bit more reckless.

Beaks: You do have a reputation for being as involved as possible in every aspect of production. Stanley Kubrick was notorious for that kind of heavy involvement, so you're in good company.

Wright: But why wouldn't you be? It's all so fucking wonderful and so exciting! I love all aspects of it. I don't really understand the science of photography. I'm not a scientist. Although I will get really into lighting and atmosphere and what I want it to look like, I don't really understand digital technology. I don't really understand the finer points of chemistry, in terms of film laboratory work. But I certainly understand that it's twenty-four-still-frames a second, and that the illusion of movement is created in the viewer's brain. I understand that as being audience participation. The idea that a film is created in the viewer's brain is the most important thing about filmmaking.

But why wouldn't one get involved with dressing Keira Knightley up? Or music or color design or palette or dialogue. It's a wonderful opportunity to learn so much! I love learning about... I don't know, Finland! The geography of Finland and the climate conditions. I love learning about the lives of people on Skid Row and their recovery. I see my career as an extension of my education. I had a shit education, so I feel like I'm making up for it now. I hope to keep on learning. It's a fucking beautiful world, and there's so much to see and learn of it.

Beaks: Are you making films based on what you want to learn? Given your award-nominated stature, do you feel pressured to take a certain type of film?

Wright: No. After I'd done two period films, I got sent a lot of scripts that were set in historical periods. But the period of a film is secondary always to the story and the characters. So the first and foremost thing one is learning is about the human condition, and what it is to be human, and to see the world from someone else's point-of-view. And then you layer it with learning about Georgian Britain or Second World War literature or whatever else it is that one can learn. But first and foremost you're always trying to learn about what it is to be a human being, and your own feelings.

Beaks: (Getting the wrap-it-up signal from the publicist) I just want to ask one last question. You're working with my favorite living writer, Tom Stoppard.

Wright: My god! Talk about education! Last week, I sat in a room with him for three days as he unraveled the complexities of ANNA KARENINA. I mean, that's like a fucking master class! You know, I didn't go to university, but I would've liked to. So the opportunity to sit there with one of the greatest minds in theater and, indeed, possibly in literature, and be talked through ANNA KARENINA... it's such an incredible privilege. I'm really interested in learning from older generations as well, and applying that to my work, and hopefully passing that on to future generations. I've got a young guy called Brady who works for me in my office, and I love being able to expose him to film and literature he wasn't aware of. I think that's really important. I just started a production company called Shoebox Films, and the whole idea of that company is to bring together the very experienced older generation and the less experienced younger generation, and have a dialogue going on. Hopefully, the older generation can teach the younger generation a thing or two, and the younger generation can do the same for the older. My wife is an Indian musician. Her father is Ravi Shankar. In Indian classical music, they have a tradition of guru and pupil. It's an oral musical tradition, so every classical Indian musician has to go study with a guru for seven or eight years, and just sit at their feet and learn how to play their instrument. Right now, I think Tom Stoppard is my guru.

Beaks: If he's your guru, let me put a bug in your ear. I think you're one of the few directors who could pull off ARCADIA as a film.

Wright: Oh, I would love to do it! I know that he tried to adapt it some years ago and didn't find a way through it. It's a great play. I hear the production is very good in New York at the moment. Shall I tell you a lovely story he told me the other day?

Beaks: Please do.

Wright: At the press night of ARCADIA in New York, a journalist came up to him and said, "Sir Tom, if you had the opportunity to teach anything, what would you teach and to who?" And Tom looked at him and said, "To whom. I think that answers your question."

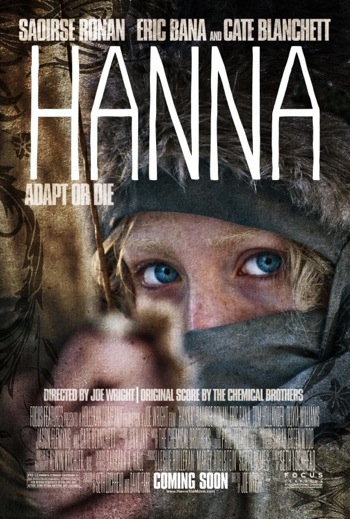

HANNA is currently in wide release. If you didn't get to it last week, please skip the shockingly incompetent SCRE4M and make HANNA a priority this weekend. You won't be disappointed.

Faithfully submitted,