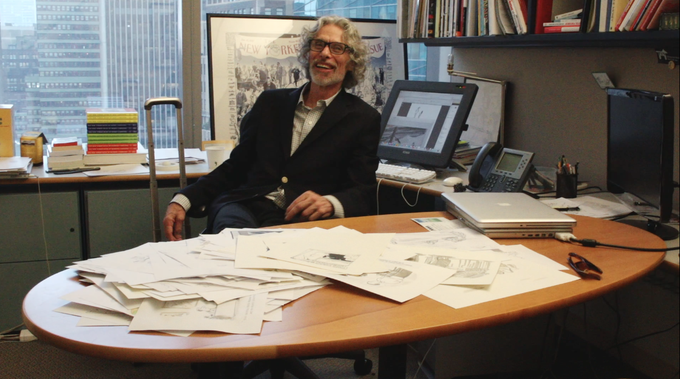

Bob Mankoff got his first cartoon printed in The New Yorker back in 1977, and has been serving as the cartoon editor for the publication for the past 18 years. He's published five books, most recently his memoir, How About Never — Is Never Good for You?: A Life in Cartoons, and has helped compile past New Yorker cartoons into several compilations, including The Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker which featured every single cartoon ever printed in the magazine on an accompanying CD-ROM. If you're wondering who the head cartoon guy is at The New Yorker, it's Mankoff.

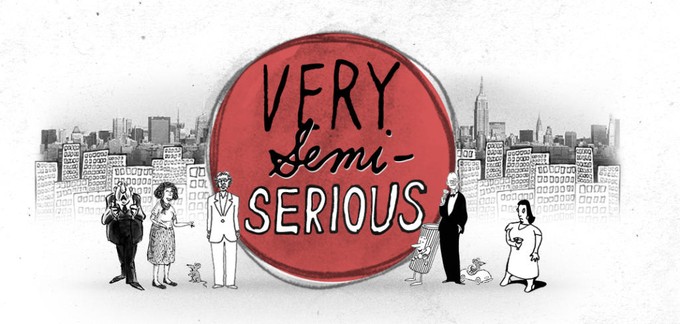

He's also the primary subject of Leah Wolchak's documentary about the New Yorker cartoonists, VERY SEMI-SERIOUS. Through interviews with Mankoff, and cartoonists both young and old who've drawn for the magazine, Wolchak examines the process of getting the cartoons into The New Yorker, from conception to execution to pitching them to Mankoff and finally, surviving editor-in-chief David Remnick's final examination. Via Mankoff and the various cartoonists, we see the wide range of perspectives, personalities, and talents that end up creating the cartoons the readers of the magazine enjoy on a weekly basis. It's a documentary about what it means to be a working artist in today's world and the bizarre, but very real struggles of having to be funny to make a living.

Based on how he came across in the doc, I was banking on Mankoff being a funny, erudite, casual personality, and I wasn't disappointed. I laughed quite a bit as he he enthusiastically relayed his wisdom on what he does, how he got there, and the way reality is changing both for himself and for cartoonists in general:

VINYARD: How did Leah Wolchak first approach you to be the subject of her documentary?

MANKOFF: It started back in 2007 when she graduated from Stanford film school. She approached me warily (laughs) with good reason, because I told her we weren’t gonna do it.

VINYARD: When did you come around and decide you wanted to be a part of it?

MANKOFF: It was a gradual process. In 2007, she really didn’t know anything about New Yorker cartoons, she was just sort of infatuated with the caption contest. Also, just from a bureaucratic standpoint, in 2007, I don’t think The New Yorker or Conde Nast was really ready to open their doors. But over time, Leah kept persisting and learning more about The New Yorker cartoons and cartoonists, ‘cause she interviewed them. She was very determined. I think her dedication won everybody over, and then the tide shifted also in terms of what The New Yorker was willing to do. I don’t know when the tipping point was, but when it tipped, it tipped completely.

VINYARD: Why did The New Yorker change their thoughts on opening their doors for the doc?

MANKOFF: I think the institution itself became more open as everyone became more involved. Maybe the branding, or social media, and maybe they came to trust Leah more, and wanted to really get the word out about what we actually did. I can’t quite remember. I guess it was a gradual process where the media institutions sort of realized they were swimming in a new world where it’s important for them to reveal what goes on behind-the-scenes, how the sausage is made. The New York Times, or any of these institutions, there’s an interest in knowing not only what the stories are, but the people behind the stories.

VINYARD: At the end of the documentary, it shows that you guys just moved to a new location at the Freedom Tower, One World Trade Center. Was that move a part of it, and has the move had any impact on the way you edit the cartoons?

MANKOFF: I’m editing them on a higher floor, so maybe there’s a little less oxygen. But I think it’s the same. (laughs) No, I don’t think it’s had any impact at all. We’re in a new place, and it’s part of the overall story about the film, which is the resilience of the institution, its need to change and adapt, for the cartoons to also change and adapt and have new blood to it and rejuvenate it. And, like I said in the film, this is the place where these people were killed, and we all, throughout our lives, use humor as a way of coping, as a way of being resilient, and I thought that was part of the overall message of the film as well.

VINYARD: Do you see any trends in new cartoonists that hint at the direction that humor, in general, is going? Do you approve or disapprove?

MANKOFF: (laughs) I better approve! Humor evolves like music evolves, or all entertainment evolves. It keeps changing and mutating and morphing. The basic melody underlying it is always the same. Observational humor, satirical humor, meta humor, all those types. Maybe I see a little more whimsy, more absurdism, more just playing with the form itself. Great freedom in blending the old with the new. It changes. I say in my memoir, “People like novelty within a template, within a cocoon of familiarity.” People don’t like complete novelty. They like a little bit of surprise, and that keeps changing. The amount of surprise they want and the context they want always keeps changing. That’s part of what new people do. I think they learn something from me and me mentoring them, but I learn something from them.

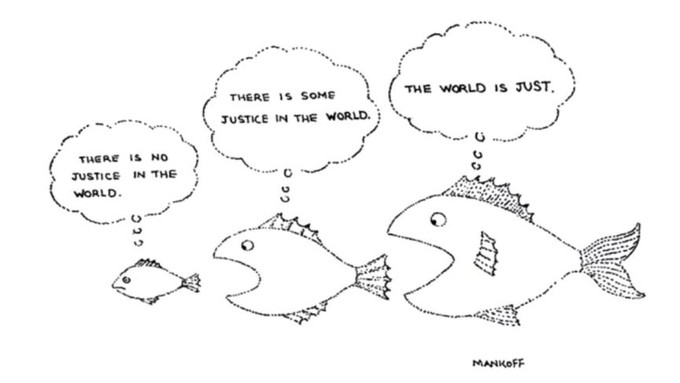

VINYARD: That ties into something you mention in your TED talk, about bridging the line between “Benign” and “Violation,” and finding the right balance. Do you think younger cartoonists are skewing one way or another?

MANKOFF: Yeah. I think within the context of The New Yorker, they’re probably slightly more violative, but still probably fairly benign. Our stock in trade really is not transgression, which is one of the main levers to make people laugh. Say something bad, something obscene, or whatever. And that’s perfectly okay, because part of what makes people laugh is just raising the emotional tension, and you will do that with topics that make people uncomfortable. For the most part, we don’t do that, I think. The cartoonists are still operating within the tradition of The New Yorker, so it’s more whimsical and absurdist than actually violative, I would say.

VINYARD: You were rejected a bunch in the early days. How long did it take you to figure out what that style that’s appropriate for The New Yorker actually is?

MANKOFF: It probably took me three years, and whatever that is has probably changed somewhat. I think what I had to do…what I say now is, “I’m not looking for cartoons, I’m looking for cartoonists.” So I’m looking for someone with a voice, a personality, a style. I had to solidify that for myself, rather than be a chameleon and be able to do everybody’s style. A lot of fairly clever people can do many different people’s cartoons or jokes, but they have no particular center or personality themselves in regards to humor. What makes stand-up comedy, for example, way more than the jokes is the personality that infuses the jokes. I think that’s certainly true of cartoons also.

VINYARD: One of my favorite parts of the film is watching you look through the various batches of cartoons and very quickly gauging whether they’re appropriate or not. Have you ever lingered on something, or gone back later and changed your mind?

MANKOFF: All the time. Only politicians can’t change their minds. There’s nothing infallible about that process. I always like to go back and re-think things. I understand that there are all these psychological factors at work when you’re looking at any particular cartoon. You might have seen too many cartoons, you might be satiated, you might be tired, you might be many other things. You factor that in and you often want to give it a second look. Sometimes you don’t have time. You’re under great time pressure at a magazine, so you want to give it your best shot. I say to the cartoonist, periodically, not every week, “Hey, if you think I passed on a cartoon you think is really great, send it to me again! Maybe I was wrong!” I think it pays to be humble with something as subjective of a field as humor.

VINYARD: The top link in the chain is David Remnick, and I liked that we got to see him enjoy his perusal of the crop. Where does his sense of humor tend to skew, in terms of what he approves of and what he rejects?

MANKOFF: He needs to take the opposite approach from me, not analytic at all. He has to put himself in the mind of the ideal observer, knowing everything else that’s going on in the magazine. I think he’s a good final check on it because for actually looking and re-looking and all of that, you always want someone else to look at it. He’s a really good person to look at it. He himself has a good sense of humor. You want someone who’s actually going to enjoy them, because frankly he’s not going to have to look at 500. I think it’s a really good process, and it’s what’s been going on here for a lot of years.

VINYARD: Do you ever work with the staff writers in terms of incorporating a topical cartoon with the articles?

MANKOFF: The cartoons can never refer to anything in the magazine. They can be topical, but if we have an article, like we do this week, on artificial intelligence, we wouldn’t even have a cartoon in the magazine about artificial intelligence or robot brains or anything. We’ll have topical cartoons, and sometimes there might be an article also about that. Maybe someone will be writing about Trump, and we’ll have a cartoon about Trump. But it’ll never be relating to the article.

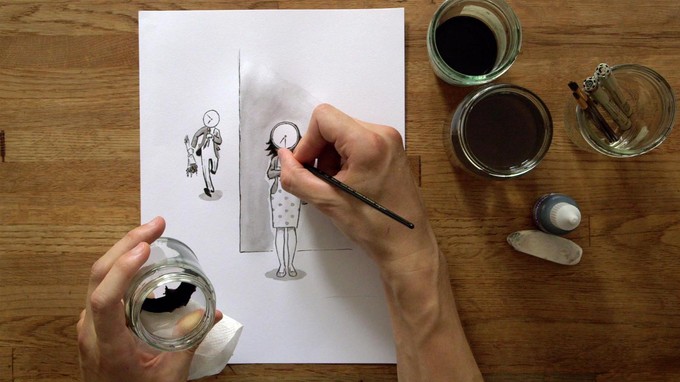

VINYARD: I’ve wondered a lot over the years about the relationship between the cartoons in the magazines and the captions, how directly they’re correlated, which one comes first.

MANKOFF: It’s more an interactive process. Sometimes you think of a line and then you’ll think up the cartoon, but remember the cartoonist isn’t walking around. They’re at a drawing board, they’re doing sketches, they’re looking at their previous cartoons. I might be drawing somebody in a boardroom, and then I might put an object in there, or I might have an idea about monetization and wealth. So I might have half an idea for a caption, and I might be drawing in relation to that caption, and then I might have the final idea for it, or it might completely change. Then, of course, you have cartoons that are just the visual themselves, so there’s no caption. You’re there, or the cartoonist is there, sketching…maybe they’re writing little half-captions, little notes that you’re jotting on the side of you’re drawing, then maybe one of them sort of takes flight and you flesh that out. If the process occurs at all in a two-stage process, it’ll be you’ll think of a caption, then you’ll try and think of a place that would be appropriate. There are verbal cartoons, quips, and then you’ll clearly go to that, but it’s much more back and forth than people imagine.

VINYARD: Aside from the caption contest, obviously, have you ever gotten a caption from someone other than the artist?

MANKOFF: Yeah, rarely, rarely. It used to be in the ’30s and ‘40s, there were gag writers. Even when I started in the ‘70s, you’d get stacks of index cards with gags, so it was a whole profession at one point. In the ’60s and ‘70s, things started changing at The New Yorker. We wanted more authenticity, we wanted the person to come up with both. We thought that was better, more authentic. But every once in a while, someone will definitely give a caption to a cartoonist. Not me, personally. I never wanted to do that. I always wanted everything to be mine. But it’s not unheard of, although it’s unusual.

VINYARD: As the New Yorker readership expands internationally, and a wider range of people are engaging with the cartoons, do you think about changing the style to accommodate the expanded readership?

MANKOFF: Uh, no. (laughs) Not really. I mean, the cartoonists have to do the cartoons. When cartoonists come in, what I say is, “Look, here’s the deal. Do the cartoons you like, things you like, hope that we like them, and then hope that the readership likes them.” We don’t do a lot of focus grouping or anything. There’s nothing wrong with that, and there’s a lot of that, and maybe there’s too much of it. I think people respect The New Yorker because there’s a certain aspirational aspect. “Let’s see what they think, what this non-focus-grouped, dedicated group of people think is good or interesting.” I think that’s our niche, and I think we should sorta stick to that instead of try to figure out what our expanding readership will like. I think our readership is expanding because more people seem to be liking what we do.

VINYARD: They’re signing up for the brand, so why fix if it ain’t broke?

MANKOFF: Yeah, they’re signing up ‘cause we’re The New Yorker. We’re not something else. And there’s nothing wrong with it. There’s plenty of other places that get all sorts of different stuff. I don’t think you’re ever going to see on the cover of The New Yorker, “15 Cartoons You Must See Now.” I don’t think we’re gonna do that.

VINYARD: In the movie, you mentioned how a lot of magazines dropped cartooning over time. You founded the Cartoon Bank 20-plus years ago to preserve all the New Yorker cartoons. What do you think the internet’s impact on cartooning and being a cartoonist has been?

MANKOFF: Well, there’s a lot of cartoons now. You see a lot of cartoons. I hope that the Cartoon Bank helps make it a viable profession for our cartoonists. And that’s the problem. There’s no great problem with the internet, it’s wonderful in the way that it distributes is. The only question is, how to monetize it, how to monetize it. How to make a living at it. I don’t know if that necessarily has become any easier. Most of the revenue being generated on the internet is by these huge corporations. I think cartooning will always survive, and actually be quite vibrant, and there’ll be lots of good cartoons for the foreseeable future. The question is will there be lots of good cartoonists making a living, or will it be sort of an avocation.

VINYARD: Like the movie shows, lots of modern cartoonists have day jobs.

MANKOFF: Exactly, and there are worse things than that. Maybe that’s gonna happen with a lot of things, a lot of things that used to be professions, even journalists, right? I mean, it may be that a lot of these things are something that you don’t earn. I guess what it’s called is “the gig economy.”

VINYARD: Yeah.

MANKOFF: You get a gig here, and a gig there, a gig there, and that may be the way it’s going. I’m pretty sure whatever I predict will be wrong. That’s my prediction, whatever I predict will be wrong. I only say that based on all my previous predictions for the rest of my life.

VINYARD: Well, I disagree, because in ’05 you expanded the caption contest to be a weekly feature as opposed to an annual one, and obviously that’s been a huge hit. What was the inspiration for that?

MANKOFF: The inspiration for that was David Remnick. I had done that as an annual thing, and he suggested we do it, so that was his brilliant idea. He wanted something like the crossword puzzle in the back. And I had really nurtured that, and I’m involved with all sorts of computer scientists at Microsoft and elsewhere, using all two-and-a-half million entries as a database to investigate the nature of humor, of user-generated humor. We’re going to do an experiment, I think, where we’re gonna crowdsource about 500 captions that people can vote on maybe tomorrow or the next day to rank them, and use that information to help choose the three finalists. So it’s been a wonderful experiment. David definitely gets credit. I guess I get credit for the idea of creating it, and he definitely gets credit for the idea of making a weekly feature, which is enormously popular.

VINYARD: To dig into your personal life for a second, you’ve admitted that you always thought you were a funny guy since you were a kid. How old were you exactly when you realized you were funny? Was that something you worked on, or something that kinda came about naturally?

MANKOFF: I think I worked on it after it came about naturally. (laughs) Maybe it’s the 5th or 6th grade when you sorta feel, “I can do this.” It’s not like being a class clown, it’s like being a wiseguy, you know what I mean? I’m still sort of that wiseguy. I still sort of fool around in that way. I don’t only make jokes in the magazine. My mantra is, “Leave no joke unjoked! If you’re thinking of something funny, say it. Even if it’s to someone in a supermarket or an elevator, say it!” Life is so dull without it, so I will joke around. That became part of my personality. Like a lot of people who have a particular ability, you hone it. Once you start to get reinforced for that and people start to pay attention for it, you start to play that card that you have, and then you notice the other people in society that play that card, the entertainers. Then you start to imagine, “I’m funny, who are these people that I’m watching on television who are funny?” Maybe the thought isn’t completely formed, but you think, “Maybe that’s what I could do, maybe that’s what I could be.” I’ll bet that’s true for a lot of people, whatever profession they end up going into.

VINYARD: Last question: I’d say what you just said corresponds with your portrayal in the movie, but I was wondering if you had any reservations. The film is going to immortalize you in a sense. Was it ever a concern for you, how you were being portrayed?

MANKOFF: The only thing that was difficult in the movie was the fact, as you’ve seen, that my stepson David died, and that that would be part of the movie. For me and my family, that was very tough, and still is tough. It’s actually still tough when I watch the movie. Humor helps us deal with it as much as humor can. But that was the only reservation I had, because we had no editorial control over the movie. Since David died in the middle of the movie and everything stopped, including my book, I didn’t even know if the movie was going to be made. Then the movie started up again, and as it shows, I started writing my book again, which was very difficult, then I think it shaped the movie. In some ways, I think it’s part of the subtext of the movie, about humor and resilience. I think Leah handled it very tastefully, but that was difficult.

In terms of how I’m perceived or immortalized, there’s a great Woody Allen line: “I don’t want to be immortalized through my work, I want to not die.” The movie’s nice, it treats me very, very nicely. If this is how people end up viewing me, that’s okay. Whatever they think about the movie is not that important to me, honestly. What will be important is how they view The New Yorker and the New Yorker cartoons and cartoonists through this movie. I think overwhelmingly, they’ll view them with admiration, so I’m happy about that.

VERY SEMI-SERIOUS is playing an Oscar-qualifying run starting today at the following four theaters: Lincoln Plaza Cinemas in NYC, The Laemmle Royal on Santa Monica Blvd in Los Angeles, the Laemmle Playhouse 7 in Pasadena, and the Roxie in San Francisco. It’ll premiere on HBO on Monday, December 7th.