It is finally here — after months of hard work, two trips to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a trip to the Toronto world premiere of THE MARTIAN, and some marathon sessions of writing, shooting, and editing with my partner James Darling and a small army of helpers, we are happy to present the full-length version of Science Vs. Cinema: THE MARTIAN. We made it as a pilot with no budget just to see what we could do, but I think it is a pretty cool demonstration of the concept. I can't figure out how to embed it at full resolution, so you might want to watch it over on YouTube.

We initially delivered Round 1 about the first 49 minutes we saw, and Round 2, about my initial reactions and film review, from Toronto. We rushed those, just to get something out there, and we’ve reused some of that footage here in the more polished, full-length discussion of the science. If you like what you see, please sign up for Science Vs. Cinema YouTube channel.

While the real product is the video, I’ve written this companion article on the science, where I go into even more geeky detail. There will be plenty of overlap, so I’d watch the video first, and then read more here if you’re still interested. Of course, you can follow the links scattered through the article if you want to know more.

In this episode, I talked to lots of people involved with the movie like the book’s author Andy Weir, the director Ridley Scott, screenwriter Drew Goddard, and actors Matt Damon, Jeff Daniels, and Mackenzie Davis. To check on the science I interviewed Astronaut Drew Feustel, and NASA scientists Jim Green, Rob Manning, Katie Stack-Morgan, Carrie Bridge, and Matt Heverly. I had other (mostly unrecorded) conversations with producer Simon Kinberg, actors Kate Mara, Donald Glover, and Chiwetel Ejiofor, and astronaut Chris Hadfield. There is just no way to adequately convey all that in an article.

My rule for science in fiction is that it is ok to cheat a little if you need to, to tell a better story. But don’t do it because you are too lazy to do the research. Let’s see how THE MARTIAN fared.

MARTIANS, MARTIANS, MARTIANS

Fiction about Mars has tracked our understanding about it over the centuries. Actually, they used to be one in the same — red point of light in the sky represented the god of war. Later people read in the presence of canals and civilizations from sketches of telescopic observations. It was a great frontier, full of our worst fears or highest hopes. It was only about 50 years ago that we successfully sent the first spacecraft to fly by mars, Mariner 4. This followed four years and six missions of failure by the US and USSR. Of course there were no aliens. So our stories changed. Maybe the aliens were there in the past and left artifacts.

Today, humans have sent more than 50 missions to Mars, although only about half of them have succeeded. Consider that when debating whether to send a crewed Mars mission. The good news is that right now we have seven active missions at Mars: Mars Odyssey, ESA’s Mars Express, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, the Mars Orbiter Mission, and the rovers Opportunity and Curiosity. This is an astounding wealth of knowledge that we can now take back to movies.

My love for Andy Weir’s book THE MARTIAN is well documented, as is my love for the film. Now that others have seen it, I’m glad so many others seem to feel the same way. I find it pretty remarkable that with all the chances to screw up a beloved property, THE MARTIAN managed to get it right. It took what was great about the book, and changed it for the screen, but in a minimal way, while preserving the character of the original material.

GET YOUR ASS TO MARS

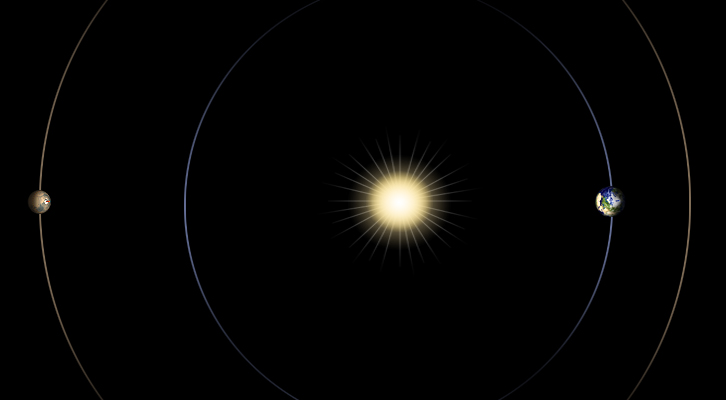

Mars is so far away that it takes radio signals traveling at the speed of light between 4 and 24 minutes to get there from Earth. The reason for the difference is that sometimes Mars is on the same side of the Sun as the Earth, and Mars is only about half an “Earth orbit” (what astronomers call an astronomical unit, or AU) away. Other times, it is opposite the sun, and so is about 2.5 Earth orbits away. Actually, the values can deviate from that a bit, because Mars has a relatively eccentric (oblong) orbit.

As a result of the large Earth-Mars distance, communication does not happen at a pace that filmmakers like. Most movies cheat on this, but I was happy to see that it was kept in as a major plot point in THE MARTIAN.

Space travel is much slower. For unmanned missions, it takes between 150 and 300 days to get there depending on when you launch and how much fuel you’re willing to use. Remeber that both Earth and Mars are moving at different rates, so you don't aim for Mars, you aim for where it is going to be. And because of the configurations of orbits, some windows are more favorable than others for short travel times.

The long travel time means you have to take a lot of supplies. Even if you grow plants en route, the mass has to come from somewhere. It comes from the air — plants are just a way of turning carbon dioxide into carbon and oxygen. So since plants don’t save you mass, you should take mostly prepackaged meals. Still, you might want to grow some because it keeps astronauts happy. Growing things remind us of home, and fresh food boosts spirits. In fact, astronauts are growing vegetables right now on the space station. It isn’t crazy, then, that the Ares 3 mission to Mars would have a botanist on board.

It also takes a lot of fuel to get there and back. But it is too heavy to take with you. So you want to set up an unmanned factory on Mars to make fuel that is just sitting there for your return. In fact, an instrument, MOXIE, being built for the Mars 2020 rover (the successor to Curiosity), will do just that. It will use electricity to create oxygen from the atmosphere. In addition to being used as breathable air by astronauts, liquid oxygen is often used as rocket fuel.

This is similar to what happens in THE MARTIAN. Watney and company are on Ares 3, but some components of the future Ares 4 mission are already in place, and are critical to the story.

Depending on how long you spend on Mars, it might take something like 500 days for a round-trip. Being weightless for that long can cause you to lose muscle mass and bone density, so you want astronauts to have artificial gravity. Gravity is a force that produces acceleration. You can mimic that with any kind of acceleration, and circular motion fits the bill. So we need to put our astronauts in a giant spinning wheel. The amount of gravity you feel depends on the radius of the wheel and how fast it is spinning.

Before I do the calculation about whether or not they did it right, first I want to share an exchange that gives insight into how the process of getting the science right on the film worked. I was at a roundtable interview with Andy Weir, Ridley Scott, and NASA Planetary Sciences director Jim Green, when I asked them about what they discussed the first time Jim Green and Ridley Scott talked on the phone.

Jim Green: It was all about the science, it was about ion engines, we talked about radioisotope power, what the space suits looked like. We talked about how to create artificial gravity. We talked about all kinds of things.

Ridley Scott: We did good on artificial gravity.

JG: Yeah you did great, I loved it.

RS: You guys told me, I think you said, if you attain 5 miles an hour on the perimeter of the wheel, you’ve got gravity.

Andy Weir: Well, it depends on the radius of the wheel. When the trailer first came out, I did a bunch of freeze frames measuring against Kate Mara’s height because she’s visible through the window so I could calculate the radius of the wheel and the rotation and I actually figured out that they would only have about 0.2 g’s in the gravity wheel part.

JG: Close to Mars.

RS: Would it need to be longer?

AW: Either further out or spinning faster. But it doesn’t matter. The point is they have gravity…

RS: We’ll bring you in next time!

AW: Well, you brought me in this time. I got technical questions. I loved it when I got a technical question through like four intermediaries from you about, “Hey can we show Watney pouring hydrazine from one container into another out on the surface?”

RS: Oh I remember that.

AW: So we played a game of like Chinese whispers until it got to me, and then I was like, “Um, I don’t think so because hydrazine is really volatile and the atmosphere on Mars is like practically a vacuum so it would boil off. And that got back up and they said then ok, we won’t do it. And I was like, “Wow, I mattered!”

To find the amount of artificial gravity, I did some of my own freeze-frames from the trailer. I estimate the length of the wheel as about 8 Kate Maras. Since she’s 5’3”, that’s 42 feet (12.8 m). Then to estimate the wheel’s spin rate, I got these screen captures, and drew a line for reference.

The first one is at 67 degrees, and the second is at 57 degrees. As you can see, that happens over about 2.09 seconds. To go the full 360 degrees, it would take 36 times that, or 75 seconds to go around once. That would only give you about 1% of Earth’s gravity. That calculation isn’t super-accurate, because it was really difficult to measure, and I’ll bet that different shots have different spin rates. But the real takeaway is that they got the right idea, but didn’t execute it perfectly. For a wheel with a 42 foot radius, it would have to spin once every 7 seconds to attain 1g — so the wheel is either spinning too slowly or isn’t long enough.

But that doesn’t matter as much to me as the fact that they showed something. You can see how they’d get it wrong though. NASA probably told them the right thing, and they had a workable design. But then when it came to the rotation rate, they just decided to go with whatever an effects artist came up with, that looked cool. And Ridley Scott, who told me he was last in his class, and failed everything except the arts, probably said, ok, go with that.

All in all though, the mission shown in the Martian is extraordinarily accurate. I give it a grade of “Mission Accomplished.”

SOME LIGHT ATMOSPHERE

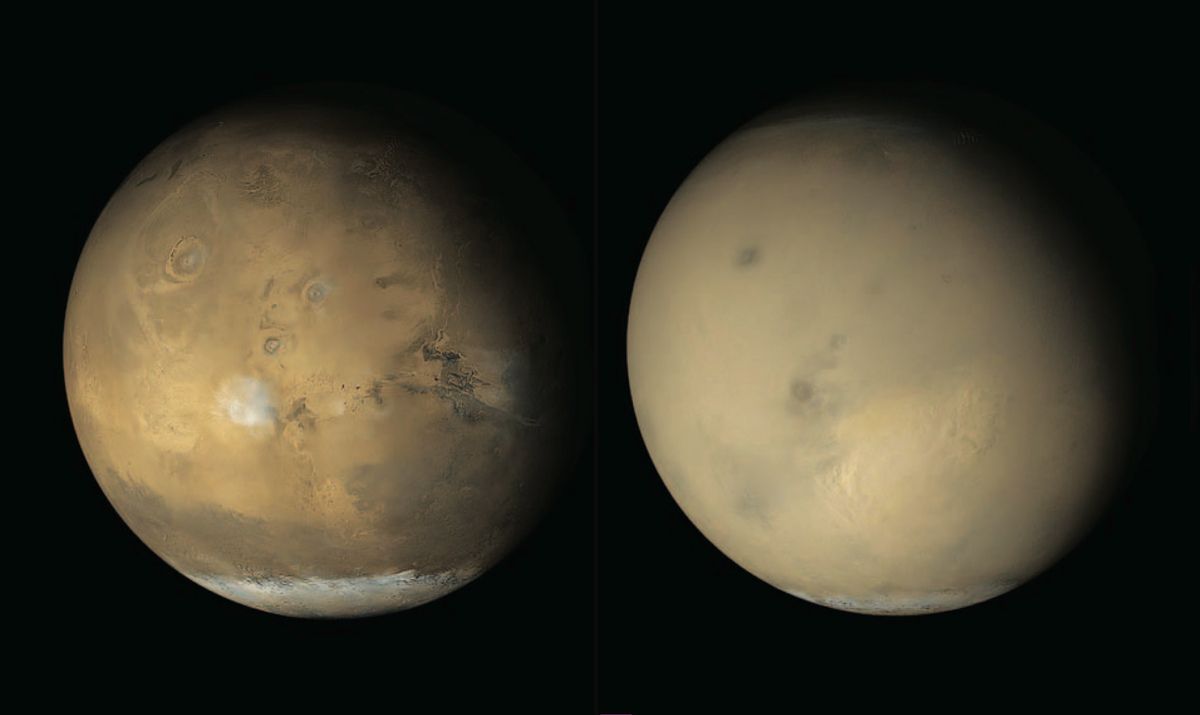

The movie opens with a violent dust storm that endangers the whole crew. Is that realistic? There are dust storms on Mars and sometimes they can engulf almost the entire planet, as you can see of two images of the same area of Mars below.

But that’s deceptive — the winds of Mars are just blowing around fine, talcum-powder like sand grains, but leaving heavier grains undisturbed. The atmosphere of mars is only about 1% as dense as Earth’s atmosphere. So there wouldn’t be enough momentum in the wind to endanger the crew.

Mars’ atmosphere is thin and made of carbon dioxide, instead of nitrogen and oxygen. This isn’t an accident — it is a by-product of physics and planetary evolution. We think all the rocky inner planets started with a carbon dioxide atmosphere that outgassed from the interior because of… volcanoes! The smallest planet, Mercury, lost its atmosphere because its tiny gravity couldn’t keep it bound to the surface. Mars is next smallest, and it lost most of it over time. Earth and Venus are about the same size, and were able to keep theirs. Only on Earth is there an oxygen atmosphere. But it wasn’t always that way. It started off as carbon dioxide, but life turned it into oxygen.

The book’s author, Andy Weir knew he was cheating a little when he started the book with a dust storm. But he needed to do that to kick off the book with a bang. I don’t mind if you cheat a little at the beginning if it is necessary to tell a compelling story. Just let us know you are doing it. And he did, referencing the thin Martian atmosphere later in the story.

In fact, when I was talking to Jim Green, he said that since THE MARTIAN was written, lightning had been discovered on Mars. He suggested it as an alternate danger, but they decided to go with the book as-written. As a fan of the book, I’m happy with that decision.

On the subject of the dust storm, THE MARTIAN gets a grade of… Kobayashi Maru. Just like Captain Kirk, when faced sure failure, it rewrote the rules on its own terms. As a college professor, I cannot condone cheating. Unless the answer you come up with is better than the right answer!

STICKING THE LANDING

In fact, the atmosphere of Mars is so thin, it is a problem for landing spacecraft there. You come so fast that parachutes are actually moving supersonically. And then the tenuous atmosphere doesn’t slow you down much. Today, NASA is testing these supersonic parachutes, but it isn’t easy, because the only place where the atmosphere is that thin on Earth is at the edge of space.

As you can see in the video, I talked to Mars landing expert Rob Manning about this at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He said some of the latest tests showed the supersonic parachutes ripping, even though they are made out of incredibly sturdy stuff.

The parachute isn’t enough. Missions with small payloads, like Mars Pathfinder, inflated airbags, and bounced the landing on Mars. But larger missions like the Mars Science Laboratory (Curiosity), used a sky crane! Rockets fired, causing it to hover, and they lowered the lander on ropes! And this all had to be done autonomously, since the communication time to Mars is so long.

The truth is, we don’t really know how to land humans on Mars yet. But they actually dodged the details in the movie, because when it begins, the Ares 3 crew is already on the panet. We know the broad strokes though -- from one of the featurettes released to promote the movie, it is clear that the Hermes stays in orbit, and they use a descent vehicle to go down to the surface. That's obviously the right move. Even the Apollo missions used that trick.

The landing site is Acidalia Planitia -- a real place. In the video, I talk to planetary geologist Katie Stack-Morgan about this. While geologists always want to go to where the cool rocks are, she said it isn’t an ideal landing spot from a safety perspective. Here’s what the region really looks like from above.

The film version also makes the rocks seem a little more dramatic than they really are, but I’m ok with that. Again, tell the most exciting story you can.

On the subject of the landing, the movie passes, but science gets an incomplete! We still haven’t finished our homework! In other words, they didn't show anything wrong, and besides, we don't even know exactly how to do it yet.

THE WEIGHTY SUBJECT OF MARTIAN GRAVITY

Martian gravity is only 38% of Earth’s gravity. To see what that would look like, when I filmed Known Universe I got on a reduced-gravity treadmill. You actually can leap higher than you can on Earth, and even walking doesn’t feel or look the same. Of course, it would be tricky to film that, so I asked Ridley Scott whether they had discussed trying to realistically show that.

He said that they calculated that in a bulky space suit, you’d come in at just under normal movement. More on space suits in a second. But I don’t really buy Ridley’s answer, because we see Mark Watney walking around without a suit, and it still looks like he’s on Earth. Ridley realized that he wasn’t really able to bullshit me, so Matt Damon chimed in with the real answer, that it was just too hard to shoot. But imagine how much more immersive the film if they had pulled that off!

On the subject of gravity, THE MARTIAN get a grade of: Spielberg! On this scale, Michael Bay is the lowest grade, and Kubrick is the highest. Spielberg and Scott know how to please a crowd, but often go for mainstream blockbuster logic over reality. I feel like Kubrick would have tried to pull it off.

ORANGE IS THE NEW WHITE

While we’re on the subject of space suits, the ones they show in the Martian look amazing. But if you really used them on Mars, you’d end up like that poor bastard who ends up on outside in Total Recall.

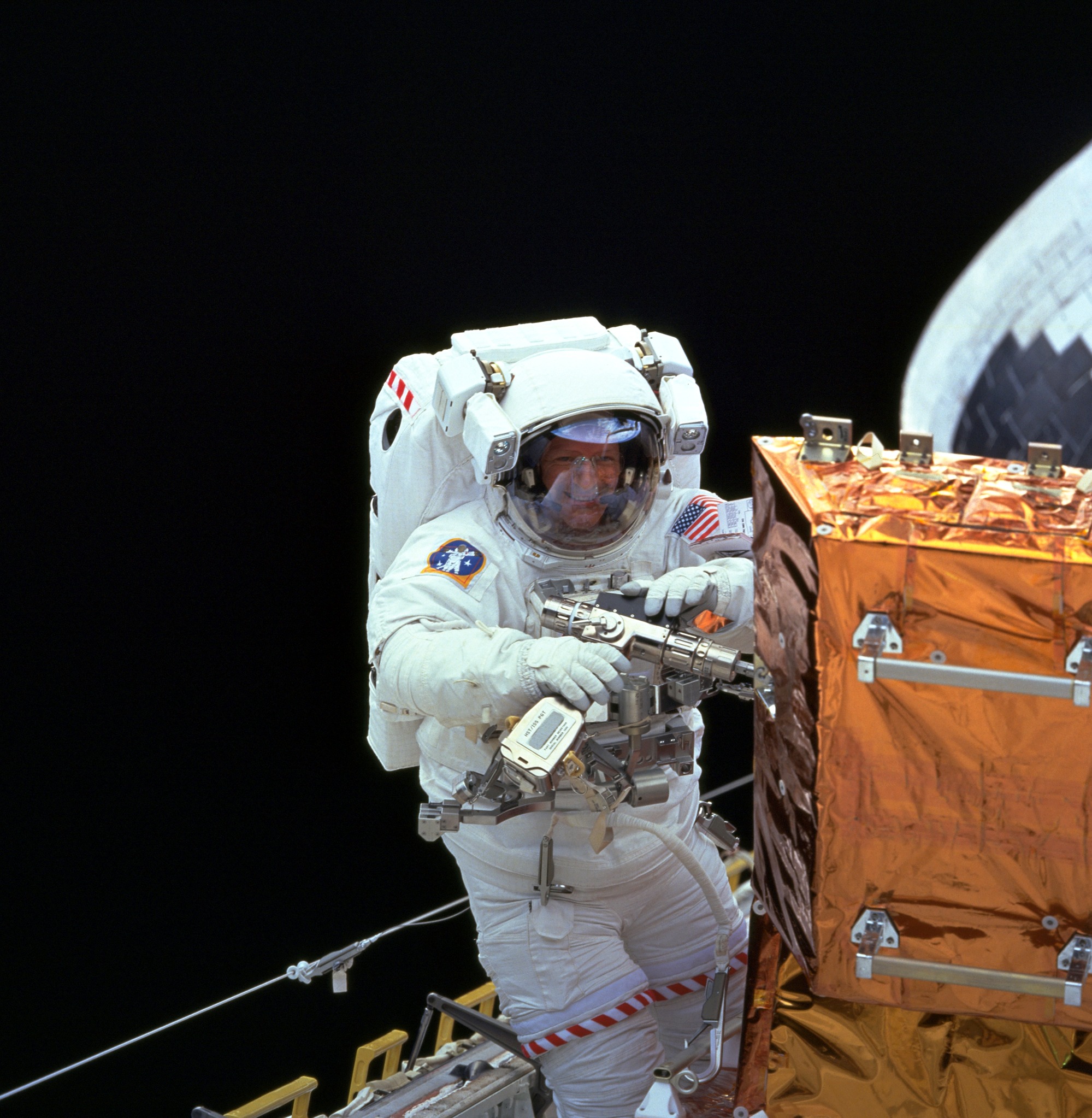

Real space suits are puffy because they are pressurized, and because they have 14 layers of material. They also have big, bulky backpacks for the air supply and climate control system. A full suit weighs more than 300 pounds. I experienced this firsthand when I tried one on at the Johnson Space Center with Mike Massimino for Known Universe.

Big, white, puffy realistic suits are seen in the Martian, but only for spacewalks. Are they too heavy for walking around on a planet? If you’re a 200 pound astronaut, wearing the suit you’d weigh:

200 lbs + 300 lbs = 500 lbs

On Mars that’s

500 * 0.38 = 190 lbs

If they had the big suits, Ridley Scott would have been right, you’d be about your normal weight. But the Mars suits shown in the movie are tiny, flimsy things. Real suits without the backpack only weigh about 110 pounds. Let’s call it 150 with the tiny backpack. When you add it to a 200 pound astronaut, that gives us a total weight of 350 lbs, which is only 133 lbs on Mars, or about 2/3 of our Earth weight. So Matt Damon should have been a little lighter on his feet, even in his suit.

Are those slim fit suits realistic? Not really. Even on Mars you need the full puffy suit and big backpack. There is a concept for a non-pressurized suit that provides mechanical pressure on the body, but that doesn’t look like what Watney has. The clearly went with fashion over science here. And it takes two people to get into a real suit. But I’ll give them that — you don’t have a movie if Matt Damon can’t change out of his suit.

On the subject of space suits, THE MARTIAN gets a grade of: Lady Gaga. The suits look expensive and flashy, but they aren’t very practical.

RED ROVER

In THE MARTIAN, Matt Damon drives around in a Martian rover. Is that realistic? Of course, we already have robotic rovers driving around the surface of Mars today. NASA started small, with Sojourner, about the size of a dog, then got a little bigger with Spirit and Opportunity, and the latest, Curiosity, is about the size of a truck!

Today’s Mars rovers can’t be driven remotely in real-time because of the delay in light travel time to Mars. To experience this firsthand, I got a rover driving demo at JPL from rover driver Matt Heverly. He showed me the cool software they use to plan out each daily drive. They have 3D images of Mars taken by the rover, and they put on 3D glasses to see every bump in the terrain. The program a day’s worth of movement, make sure it is safe, then upload it to be executed on Mars.

NASA is also developing a human-piloted rover. When I went to visit Johnson Space Center for Known Universe, I got to do a little stunt driving racing the manned rover prototype that NASA is planning for Mars trips. It has a pressurized cabin so astronauts don’t need a space suit, and it has six sets of independent wheels. These let it go up even 40 degree inclines. Here I am posing beside it with astronaut Mike Massimino.

The rover in THE MARTIAN looks a whole lot like the real NASA gear. And in reality, today’s NASA version is more like a concept car — it is used for research. The real one will look different. I wonder if it will have machine guns?

So we’ve seen NASA scientists remotely driving on Mars today. And they’ve also got a concept car for real astronauts that looks a lot like the one in THE MARTIAN. On the subject of space cars, THE MARTIAN passes inspection.

MACGYVER OF MARS

Stranded on Mars, with no way of communicating with Earth, and without enough food or water to survive, Mark Watney has to get creative.

The book has all kinds of cool calculations and chemistry. Andy Weir goes through the chemical reactions necessary to produce water from hydrazine, for example. He gets the principles right, even if some of the detailed calculations are a little off. The movie doesn’t go into nearly as much detail, but it does preserve the end results of what is in the book.

Watney also has to make food out of almost nothing. Could you grow potatoes in space dirt?

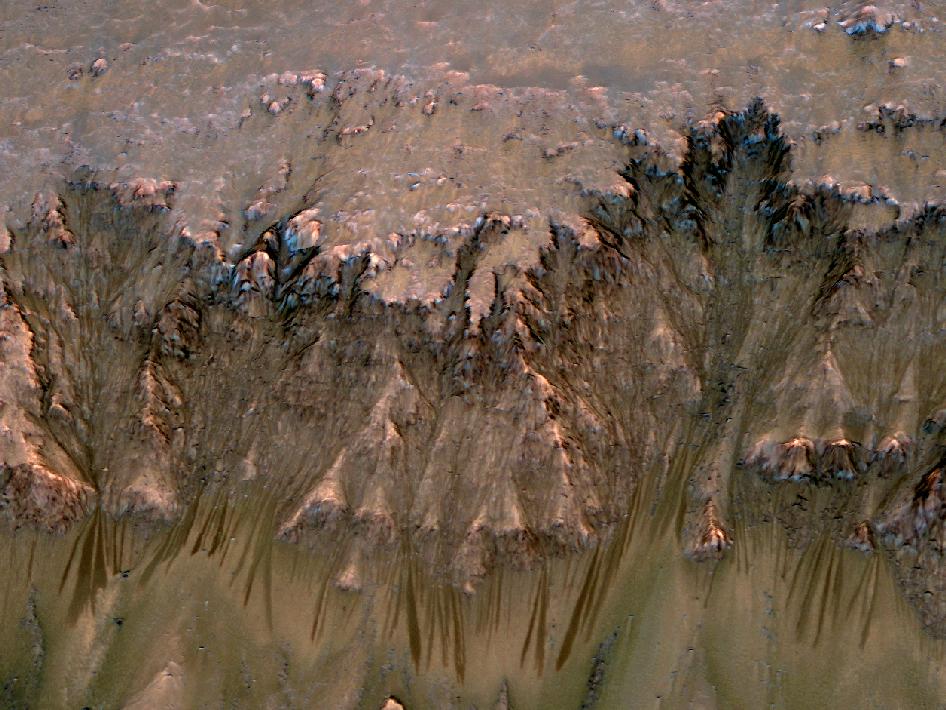

Early experiments from the 1970s-era Viking landers suggested that Martian soil would be too acidic, or too full of oxidizing compounds, to be able to support life. These oxidizing agents are perchlorates, and they could be a problem for humans on Mars, if we ever try to colonize the place long-term. Did you hear about the recent discovery of flowing water on Mars? You can see it seeping out in the image below. It could only remain briefly liquid because it was so salty from these perchlorates.

But like on Earth, the soil chemistry varies by location. In 2011 the Phoenix lander found that at its location the Martian soil was actually a bit alkaline, and the soil was pretty benign. It even had nice things for plants like magnesium and potassium. It doesn’t have organics, but that’s why Watney added poop to it!

Now I’m still not sure if you could grow plants in Martian soil, but I love the fact that Mark Watney’s a botanist! If anyone can do it, he could, and that tells you that in the Martian universe, NASA was planning tests like this.

Finally, when it comes to communicating with Earth, Watney does something very cool. He goes and retrieves Mars Pathfinder and the Sojourner Rover. It looks just like the real thing, thanks to help from NASA. And in the movie, they do exactly what the real NASA would do — have a team get one of the prototypes out of storage so that they could recreate what the astronaut is doing.

Mark Watney is doing exactly what a good engineer or astronaut would do. Take the most important problem, solve it first, and then solve each other one in turn. On the topic of space MacGyvering, THE MARTIAN doesn’t just pass, it gets the best grades since APOLLO 13.

THE RIGHT STUFF

Counting up the ways Hollywood screws up astronauts (and thus movies about space), is a sad, Sisyphean exercise. Take ARMAGEDDON, where they inexplicably train oil drillers who behave like children. Or PROMETHEUS, where the model for astronauts seems to be Shaggy and Scobby Doo. And let’s not forget the long string of randomly homicidal astronauts like ones that the crazymaking black hole produces in EVENT HORIZON, that meat dude in SUNSHINE, and even Matt Damon himself in INTERSTELLAR. Hollywood always tries to inject artificial drama by making their astronauts crazy and stupid. It takes me completely out of a movie. And I’m not the only one. I talked to astronaut Chris Hadfield at a party for THE MARTIAN premiere, and he said the ridiculous behavior of the astronauts in GRAVITY ruined it for him.

Real astronauts are the exact opposite of this. They are cool under fire and amazing at teamwork. They undergo rigorous psychiatric evaluation, and NASA chooses teams whose personalities mesh.

The realistic portrayal of the astronauts is my favorite thing about THE MARTIAN. There is no villain! The crew here works together, jokes around and cares for each other, and they don’t have stupid fights for no reason. They are all also really smart, just like real astronauts. Given that Ridley Scott is a fan of dumb crews on his space travel movies, I’m giving most of the credit here to screenwriter Drew Goddard. But it also helps that they talked to people at NASA, and sent people on visits.

They also got the spirit of NASA right, including showing how teams make their decisions. They sometimes clash, because they are focused on different priorities. JPL is focused on unmanned missions, Johnson Space Center is focused on human flight and the needs of the crew, and headquarters is focused on politics and public perception. They aren’t afraid to argue — making people defend their arguments is a big part of science and engineering — but they hash it out and come to the right decision in the end.

I also liked how they didn’t portray NASA as stereotypical nerds. Scientists are just regular people. They’re men and women, and they come from all kinds of cultural backgrounds.

My one nitpick is that things look a little too Hollywood. The astronauts and NASA employees all look like movie stars, and the sets all look like they were made by designers instead of engineers. But I do understand that. I’d rather have a blockbuster seen by a lot of people, than a wholly immersive flop.

Overall, for the portrayal of NASA and astronauts, THE MARTIAN is one of the few films in history to get it right. It is right up there with APOLLO 13. Does it bother anyone else that Hollywood can only do NASA right when they are telling a mission-gone-wrong story?

THE VERDICT

THE MARTIAN failed on its portrayal of Martian gravity, and cheated on the dust storm. But it gets high marks for the portrayal of space travel, for realistic rovers, for scientifically accurate MacGyvering, and for a realistic portrayal of NASA and astronauts. THE MARTIAN is a huge win for science!

I’m so excited that we live in an era when blockbuster science fiction is dramatic, fun, has top talent involved, *and* gets the science right. When NASA and Hollywood can work together and elevate each other's game.

A ton of the credit for THE MARTIAN working as a film, and preserving the science, goes to screenwriter Drew Goddard. He’s a fan of science and scientists, having grown up in a town full of them, Los Alamos. He called the book “A love letter to science,” and convinced the studio that preserving the science was the only way to make the film. Either do it the right way or not at all. That idea resonated with Matt Damon too, as he explains in the video. Of course Drew Goddard was originally scheduled to direct, but when Ridley Scott took over, he loved the script and didn’t see the need to change it.

As NASA’s Jim Green put it, he was the Apollo generation, but today’s kids are the Martian generation. I was inspired to be an astronomer when I saw Star Wars as a kid. The first human to set foot on Mars might just be a kid in the movie theater today, who is inspired to study science, and to become an astronaut, all because of THE MARTIAN!

Follow us at: @sciencevscinema, email us, or subscribe to the YouTube channel.

- Copernicus (aka Andy Howell).