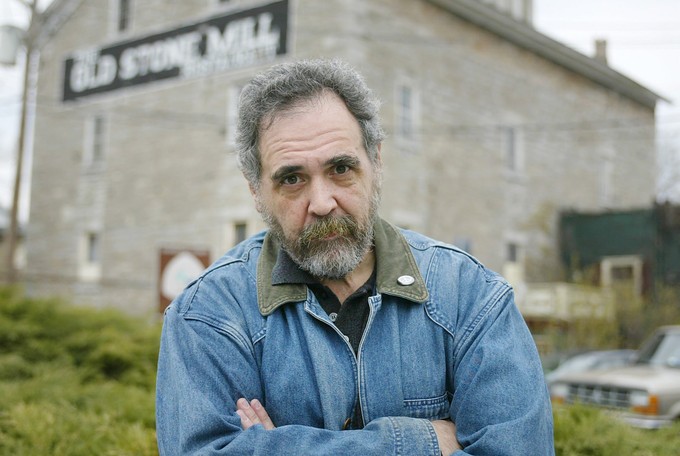

Crimmins, who now lives in the woods upstate, says in a recent scene that there are a couple of things he still wants to accomplish, to “put my little tile in the grand mosaic of life. And those two things are, of course, I’d like to overthrow the government of the United States. And I’d like to close the Catholic Church.” - from New Yorker’s recent profile on Barry Crimmins.

Barry Crimmins is one of those guys who you may not have heard of, but has certainly had a direct impact on some folks you probably have heard of. Folks like Denis Leary, Steven Wright, Paula Poundstone, Tom Kenny and the director of this documentary, Bobcat Goldthwait, all played Crimmins’ two Boston comedy clubs, The Ding Ho and Stitches, and were directly influenced by Crimmins trademark brand of confrontational, acerbic comedy. Despite his notoriety, he has eschewed many forms of mainstream success, and now, in his ‘60s, lives in a snowy cabin in upstate New York where he lives a peaceful, isolated life removed from showbiz and many of the distractions of mainstream living.

But there’s something in Barry’s story that sets him miles apart from his comedy contemporaries. In one of his acts, he opened up about a traumatic event of his childhood that forever defined the way he looked at the world; he was repeatedly raped by his babysitter’s male friend, which finally stopped when his younger sister came to the basement and witnessed the horrible act taking place. Barry continually says that he almost asphyxiated on the pillows his face was being shoved into; the fact that he even survived inspires the line he utters that gave the movie its title.

It goes beyond mere activism: in the early days of America Online, Barry was shocked to find that there were many official chatrooms comprised of pedophiles file-sharing child pornography and the like, and set out on a quest against AOL’s lack of control over their own chatrooms. For evidence, he posed as a pedophile himself, and the vast collection of horrifying images he amassed helped bring down this ring of chatrooms, at the cost of the huge emotional toll it took on him. His old friend, Goldthwait, was inspired to make a documentary about Barry, his career as a comedian, and his bravery in fighting, both emotionally and literally, against the demons that nearly traumatized him for life and almost killed him

Despite Barry’s bravura, what happened to him as a child is still obviously a very sensitive subject for him to discuss, and it was clear when I met him and Mr. Goldthwait that they had been emotionally drained by talking over this subject mater ad nauseum, so we kept it somewhat light, talking about their history together, their respective approaches to comedy, and the struggle of making a piece of entertainment that deals with something as horrifying as child-rape:

VINYARD: How’s the day going so far?

CRIMMINS: It’s good. We’re doing well.

BOBCAT: It’s not like…when you do a narrative, you’re talking about the story, and the structure, and the character. When you do a doc, you’re talking about real people, and you’re talking about real life.

CRIMMINS: And, in this case, our lives.

BOBCAT: I hope if the movie works for folks that it’s a mixture of a lot of things, and entertaining, but our personalities…we’re not used to being this serious for so long!

VINYARD: Let’s talk about your beginnings in comedy. You guys met in the ‘80s?

CRIMMINS: ’79, in Skaneateles, New York. S-K-A-N-E-A-T-E-L-E-S. I’d been around the country doin’ comedy, then my buddy “Skeeter” Crossley on the bar in “Skinny Atlas”…I wrote this pitch to him about how comedy’s coming up. I wish I could find it.

BOBCAT: Really great.

CRIMMINS: It was really depressing, ‘cause I was right.

BOBCAT: You went, “This is gonna be the wave. Plastics!”

CRIMMINS: That was it. Anyway, I’d been doing it with this one guy who’s in the movie, Steve Leahy, he was my partner. We wrote in our native hometown. The same people came to the show every week, so we wrote a new show ever week, and by “we” I mean me. Then Steve left, and I put an ad in the paper to see if anyone else wanted to do it so I could continue the show, and he (gestures to Bobcat) showed up with Tom Kenny. In my door walks Bobcat Goldthwait and Tom Kenny, “Bob” Goldthwait at the time. They became “BobEnt”, Bobcat and Tom Kenny, because they were mocking me. There was a chef at the restaurant named Barry, so people would call the resturant to figure out how to do these shows, and so whoever put the ad in put “Bearcat” because someone called me “Bearcat.” I never in my life said, “Hi, I’m Bearcat!” Not once. When I played high school football, we were watching THE ALAMO one day, and John Wayne says of Richard Widmark, who’s playing Jim Bowie, “He’s meaner than a little bearcat!” And I was…as an untreated victim of rape, one thing is it makes you a lot better of a football player. *laughs* ‘Cause you’re kinda numb, and you wanna see if you can feel anything, I was a little bit of a K.O. man. I was “meaner than a little bearcat,” and it stuck with some people. I answered to it, but I never…

BOBCAT: He never called himself that.

CRIMMINS: Ever. They were mocking me. I knew they were mocking me. And they didn’t break for well over 25 years.

BOBCAT: I always lied, and said, “No, man, we were already “Bobcat and Tomcat when we met!”

CRIMMINS: And I’d just go, “You’re so full of crap.”

BOBCAT: This guy decided to call himself some sort of cat, and then I go, “That’s not…he can’t do that, because (Barry) was the first cat!” And then Tom and I were making fun of you, and he was like “Motherfuckers!”

CRIMMINS: I knew it. I always knew it. You were mocking me. And it’s kinda snotty.

BOBCAT: “These snide little fucks!”

CRIMMINS: Bastards. But Tommy was smart enough to dump it.

BOBCAT: Yeah, yeah, but his name is easy to prononuce.

CRIMMINS: Oh yeah…GOLDthwait.

BOBCAT: Goldfarb.

VINYARD: So Barry was already influencing you when you guys met.

BOBCAT: Yeah, before we met him then I guess. He truly did become a mentor. Barry’s the first counter-culture person that I met that wasn’t like condescending or looking down at us. He saw Tom Kenny and myself, who were- I have no idea why, because we were kids…

CRIMMINS: They were so funny.

BOBCAT: …but why we were so angry. Our teen angst.

CRIMMINS: They were hilarious. They were 15, but digging in the trenches and doing biting analysis of society and making fun of pop culture in a really biting way. HAPPY DAYS was big then, and they were like killing it. They were just very funny, and it was just like, “Wow, these kids know bullshit when they see it, and they’re 7-years-old!” On the other hand, I always say this, but it’s true, they’re asking me for advice on how to get prom dates. It was like they were really biting and whatever, and then really cute and dear, and you wanna protect them. I was there when the shells cracked open, and out they came.

BOBCAT: Barry was a guy on stage who was always honest and was funny, but did what he wanted to do or say, and really was just true to himself. As a kid, I was just watching this guy, and going, “This is the most successful man in the world.” It’s true. But he was sleeping in the car or by the furnace. But seriously, I was like this guy…

CRIMMINS: Yeah, I was sleeping in a ratty old basement of a reclaimed mill that had been a grist mill forever, so there was, you know, rats around…I learned to be friends with the rats after a point, but it was…I wasn’t in a great situation, but it was the price I was paying to become a comic. I would do homeless benefits when I’d come to Boston, and people would say, “Why do you do homeless benefits?” And I’d be like, “Well, I’ve been homeless!” They never would print it. You get it into an electronic interview obviously, live on the air, but they never would print that. But it’s like, I’ve been homeless. I know what it’s like to not have somewhere to go. To become a comedian, I lived ourdoors in the snow belt in upstate New York in the middle of the winter. It’s my hometown, and I knew different barns and stuff I could sneak into, but I mean it was cold! When I got to Boston, I was homeless, I’d go…-

BOBCAT: Was it a construction site?

CRIMMINS: Yeah, I sorta lived at this construction site for a while. But I was workin’. I’d go to labor pool, and I’d take these awful jobs and work for three or four days, and then go rent a room at the Y where I had a TV, so you could watch the baseball game. Take a few bucks and buy used books, and sit and read. Buy a 12-pack of beer, and just sit there and kind of…you turn the air-conditioning on, ‘cause it’s really hot. Now it’s summer, and I’m there. Then I hustled the Ding Ho (comedy club) up. Then when I got the Ding, August 2nd I got a job at the Ding, and that was the day Thurman Munson was killed, so it always stood out in my mind. I almost didn’t go to work, because I just thought…those days they had those five-minute news briefs from the networks, and I just saw this picture of Thurman Munson and went, “Oh, no” and almost didn’t go. But I went. There were so many close calls. I mean, I ended up in Boston by mistake. I was hitchhiking to New York and it was raining like hell, and the guy said, “I’m goin’ to Boston,” and I said, “Screw it, they’re in the American League, I’ll go to Boston.” That’s how that happened. Talk about luck and good fortune. I mean, this horrible thing happened to me, but again and again I’m fortunate. It really started when Bob and Tommy walked into my show.

VINYARD: Do you think Boston was a good place for your type of political and confrontational comedy?

CRIMMINS: Well, Boston was good because…first off, I’m Irish, so I could take on some of the racism of that town as an Irish guy. I could go toe-to-toe with it there a little bit. But also ‘cause there’s a very progressive element there. I got to know Howard Zinn, and he sort of mentored me, so I was pretty good. There was always a lot of action. These people would see my act and they would ask me to do benefits, and I’d learn more and more and more. Because I wasn’t a coke guy, I could get up in the morning and read, do whatever, and my act became more and more complicated. It wasn’t always appropriate for comedy clubs, and eventually I realized that comedy clubs, in many cases, play to the same demographic as professional wrestling. I’m never gonna get rid of professional wrestling, and that’s not a cause of mine. I don’t care. But I just know demographically, we don’t have a lot of crossover in fans.

BOBCAT: I do. *laughs* I do!

CRIMMINS: And some cool people are involved with that. I ended up turning with all these musicians. (Bobcat) turned Jackson Browne onto me, and I toured with Jackson Browne because Bob hooked me up. He did one show with him, then they asked me to do half the tour, and then I did another show or two, and then they asked me to do the whole tour. This was someone drivin’ up to New Hampshire to do a gig, and I’d be talkin’ about death squads and stuff, and then listen to Lives in the Balance on the way home and think, “Maybe Jackson Browne would like my ask,” and then five months later I’m on tour with him, thanks to Goldfarb. So it’s just been amazing.

VINYARD: There’s that great clip of you in the documentary with Billy Bragg.

CRIMMINS: Billy, yeah.

BOBCAT: Interviewing with Bragg, I totally went “Chris Farley Show.” “Remember when…?” I was an idiot. I was really happy that he would do the movie.

VINYARD: Were you influenced by the political aspect of Barry’s comedy?

BOBCAT: What’s funny is that- I never really brought this up, but it’s kinda funny- I don’t know if I was influenced, but I did know that it was okay to talk about stuff like that. This persona that I had in the ‘80s and ‘90s, if you go back to my first HBO special, which is probably in ’83, I’m doing Contra material, I’m doing anti-Reagan material. So probably that was influenced by Barry, but also knowing it was okay to say these things onstage. In hindsight, I think people remember this persona from movies I did, but there was always some content in it.

CRIMMINS: Always.

BOBCAT: It’s funny, but I don’t really concern myself too much with how people look back at me, you know? ‘Cause I’m always so busy trying to make the next movie. This movie’s really fuckin’ it up, you know? Normally I make a movie, and at this point, I’m onto the next one, but…

CRIMMINS: Back to the basement, buddy. Another lap, straight down those stairs.

BOBCAT: But the fact that (the movie) is getting a much bigger notice than I imagined is more time being spent promoting it and stuff like that.

VINYARD: Aw, shucks.

BOBCAT: Yeah, my diamond shoes are too tight. But I’m really overwhelmed by the response, and I hope the movie works for people, and it seems like it is. Normally, I tell a story and it’s how I see the world, but this time I was telling my friend’s story. There’s something that resonates, and I think it’s a bigger story than Barry and I. I’m just trying to not screw it up.

CRIMMINS: I think one of the parts of the story is the resonance and importance of the story of friendship, and being a good friend. We’ve been good friends to one another. A lot of the movie’s about triumph. Not just setting a good example, but livin’ it. Not talkin’ about it, but standin’ up and doing something. He put his whole career on the line to make this movie with me. That’s what indie filmmakers do. He puts his whole career on the line for me. That’s a pretty big act of friendship, and I’m glad it’s paid off. He deserves anything he gets out of it. At every turn, when it was a choice between what he thought was my well-being or the movie, I always came first. I’d be the one arguing for the movie, and he’d be the one going, “No, we gotta protect you!” He’s just a sweetheart, the best guy ever. We really named the movie the right thing.

VINYARD: Can you talk about the state of comedy back in the comedy boom of the ’80s versus now?

CRIMMINS: I don’t think there was that much political humor. Did you think so, Bob?

BOBCAT: Not that much.

CRIMMINS: There’s always been a surface level, “take what they feed you and respond with talking points” stuff, and I hope that even pretty early on, I spit that bit. I think that Bob’s approach was so…he was hilarious, and he’d hit these real heavy points amidst this flurry of activity. He smuggled so much substance that no one would really…they’d take the sizzle, and forget the- I’m a vegetarian, so I can’t use that. I think there’s a little more going on now than then.

BOBCAT: Probably more now. It’s weird, I don’t really follow comedy too much, mostly because I don’t want to be influenced by other comedians.

CRIMMINS: Same here. Keep your palette cleansed. That’s why I don’t care when people want to talk to me about THE DAILY SHOW and stuff. I don’t know, I never watched it. It wasn’t because I was jealous or whatever, good for them. They did well, and they’re nice people, good for them. But it’s something I never thought in terms of, because by whatever, 11 o’clock at night, or whenever it was on, I’d already been thinking about…I was sorta done with the day’s news. By then, I wanna watch Turner Classic Movies or the ballgame, or something.

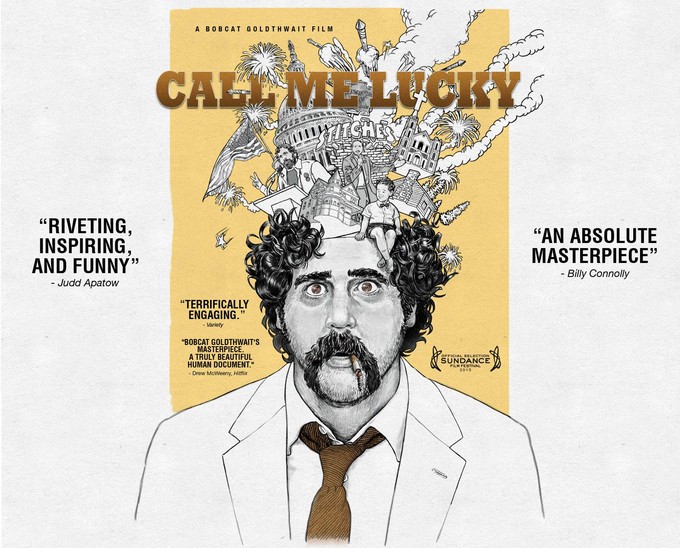

CALL ME LUCKY opens today in New York, Washington D.C., L.A. Orange County, and Austin, and will expand through the end of September.