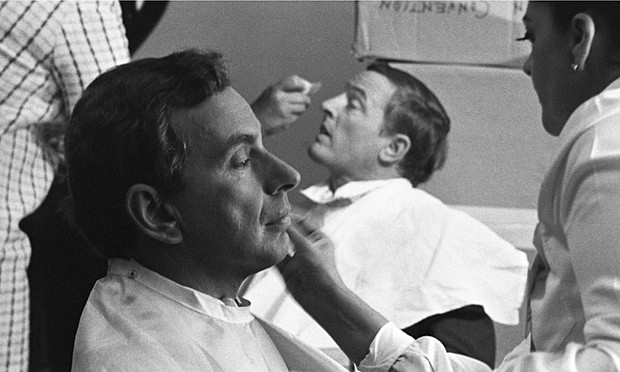

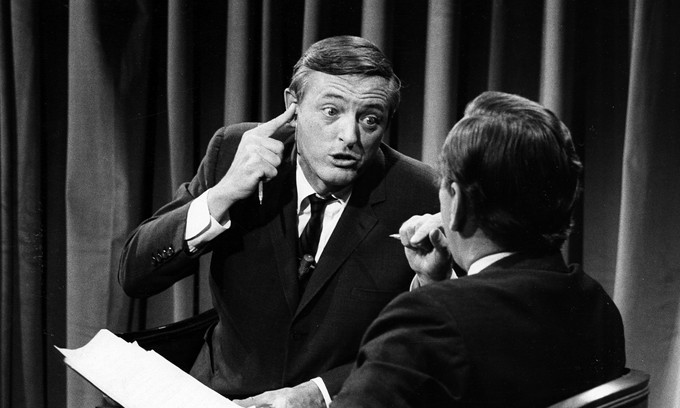

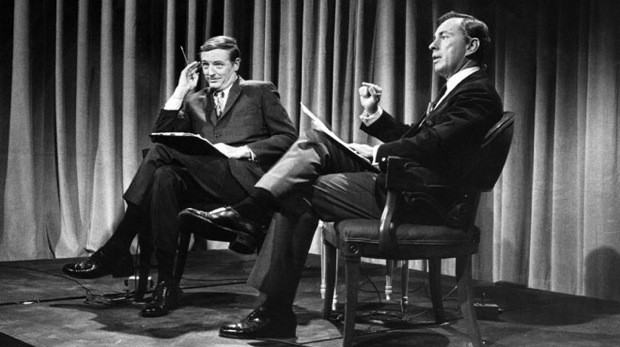

In 1968, ABC hosted a series of debates between conservative pundit William F. Buckley and historian/novelist Gore Vidal to coincide with the Republican and Democratic National Conventions of that year. Given the tumultuous political climate of the time, they surely anticipated a heated debate between two of the most prominent thinkers of their respective parties. What they couldn’t have expected was that the conversation would quickly turn into a feud that captivated the tens of millions viewers watching, and that would linger on for the remainder of both Vidal and Buckley’s lives.

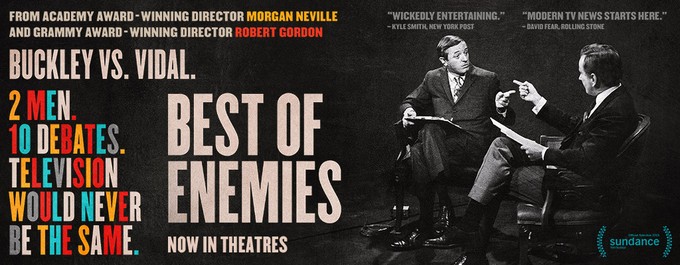

Academy Award-winner (for 20 FEET FROM STARDOM) Morgan Neville and Robert Gordon have crafted a documentary about the debates titled BEST OF ENEMIES, and while the film is ostensibly about, as Neville says, “two old, dead guys talking in a room 50 years ago,” the conversations remain cracking and riveting as the pair sizes each other up and continually edges right up to (and eventually crosses) the lines of civility and good taste. The intensity of their verbal battles reaches such heights that the film becomes very comical, and there’s great joy to be had in watching these two intellectuals degrade each other and grow increasingly contemptful of the other’s oratory abilities.

While my chat with Gordon and Neville centered around their film, and their efforts in making it the effective, balanced work that it is, but we also discussed the difference in media between then and now, the anti-intellectualism of contemporary America, and why the youth of the nation seems so complacent when compared to their Vietnam-era counterparts:

VINYARD: You guys had worked on a few music documentaries before this.

GORDON: Before we took up opera. *laughs*

VINYARD: How did you guys first meet? How did this collaboration come about?

NEVILLE: We met almost 15 years ago. Somebody who kind of mentored both of us, a music writer named Peter Guralnick, introduced us. Robert was finishing a book on Muddy Waters, and had an idea of making a documentary, but was about to throw in the towel. When he mentioned to me, I jumped at the idea. Couple of months later, we were driving around the Mississsipi Delta, making a Muddy Waters documentary (MUDDY WATERS: CAN’T BE SATISFIED). So that’s how it started.

Though we’d made music films, even the music films are about something else. They’re about race or civil rights or gender. Music is like a Trojan horse to tell a different kind of a story. In a way, doing this film felt very much the same. It really did not feel different.

GORDON: Two characters, and using them to talk about larger situations. If you have the characters, you can tell an emotional story, you can get invested. It’s not like a polemical story where you’re stuck with an idea, and it’s educational but you can’t really invest yourself. I was taken by the ideas here at the very beginning. I loved what they were talking about in the raw debates. It didn’t take long to work our way right up to the characters, and go back to the ideas from there.

VINYARD: On the surface, the subject seems like a dry, almost outdated-

GORDON: Make it your lead, please, that it’s not. *laughs*

NEVILLE: Because ultimately, at its essence, it’s about two old, dead guys talking in a room 50 years ago.

VINYARD: How’d you guys see the inherent cinematic quality in that?

GORDON: That was the biggest challenge.

NEVILLE: But I know what we saw, which was…it was operatic. There was huge stakes, huge drama, tragedy, opera, all playing out.

GORDON: Drama, drama, drama.

NEVILLE: I think our job directing was just to use every tool to make the most cinematic film we could about talking heads, which meant music, graphics, archives, and everything else. But the material was inherently dramatic.

VINYARD: What do you think the stakes were?

NEVILLE: Uh, the nation. It sounds grandiose to say it now, but in 1968, people really felt like the country was coming apart at the seams. There was brewing of a civil war happening. Vidal and Buckley were surrogates for the left and the right, for what was happening out in the streets of America. What was happening in the streets of Chicago, they were having the same arguments about the have and have-nots, about social conservatism and liberalism, and drugs, and homosexuality, and minorities, and integration, and all these things. They talk about a lot of the issues we’re still grappling with, but in the most heightened time in America.

I think they really, deeply believed that the stakes were huge. We’ve been talking about it today, it’s the thing missing from punditry today. You feel that no one even believes what they’re saying, and the stakes are so unimportant to anyone o TV. They’re just trying to get the better line.

VINYARD: Do you think that back then, they were allowed to be a little more upfront about their upbringing and their education in a way that pundits now maybe aren’t as comfortable with?

NEVILLE: Sure, for a number of reasons. I think there’s an anti-intellectual strain in America that’s only gotten worse over the past 50 years, in part because of television. You get to the point now where…not that George Bush Jr., George W., was a towering intellect, but he did go to Harvard and Yale, and pretended he didn’t! Even Obama, who’s a very articulate speaker, kind of has this everyman accent he goes into when he’s out campaigning on the trail that, to me, is just kind of embarrassing. There’s a kind of “people pretending they’re dumber than they are” thing that goes on, and politicians do it all the time now. Pundits do too.

GORDON: Pundits are more about acting than about ideas.

VINYARD: Attitude.

GORDON: Attitude, and you get groomed. There’s no stakes. The stakes are the ratings. This was an odd time when Vidal thought if Buckley won, and Buckley thought if Vidal won, that the nation would corrode.

VINYARD: And there were huge audiences for the debates.

GORDON: That’s the other great thing. The Fox audience is defined as the Fox audience, the MSNBC audience is the MSNBC audience. Here, you had a wide swath of the culture, of the demographic, watching, and I think these guys knew you could change minds. “I want to be on TV because I could reach into to the hearth of america. I can not only reinforce the ideas of people who believe in me, but I can take people who disagree with me and reach them, and maybe sway them my way.” There’s no one on Fox who’s gonna reach someone who didn’t tune in because they already believe.

VINYARD: No one calls the TV a “classroom” anymore.

NEVILLE: It’s an echo chamber.

VINYARD: Another thing that has changed since ’68 is the amount of students in college, which increased heavily during Vietnam. People are more educated now, on average, than they were at the time of the debate, yet these guys are able to speak with a very patrician, eloquent, sophisticated cadence and still amass ratings. Now, if they’re perceived as intellectual or “elitist,” no one will care and no one will watch them. Why do you think that shift has happened?

GORDON: Like Buckley would say, “I think what you really mean to ask me is…” *laughs* Why is it that the network executives, who are college trained and who are bright enough tor each the upper echelons of the mass media, why do they insist on dumbing everything down? Why don’t they trust the audience? It’s really about trusting the audience. In ’68, nobody knew what… I don’t know, I can’t think of a word that Buckley would’ve tossed around, but…people didn’t get many of the references. That didn’t stop the network from having them on. They knew, “If we have these guys on, we’re gonna go over the heads of many, but that’s okay!” In a way, I think people aspired: “Anything I didn’t get, I looked it up.” My question is, what happened to trusting the audience?

NEVILLE: So much of what this confrontational kind of TV today is that they’ve engineered these moments where you can’t look away. You don’t have to be educated or uneducated to be attracted to looking at a car crash. It somehow appeals to the basest instinct in us all, which is to say the broadest instinct, which means the most highly-rated instinct. I thik there’s an aspect of that there too. It’s having no trust in your audience, at all, and trying to trigger the inner hamster to get another pellet.

VINYARD: By not pressing the button. I’d say now, we’re having as polarizing of a conflict among young people as we had at the time of the debate, but you don’t see a lot of that debate. Like you said, it’s all fractured, it’s all compartmentalized. Do you think that the internet and Twitter and stuff have sort of decentralized those debates?

NEVILLE: Actually, I’m just thinking about why you don’t see that kind of debate between our intellectuals and certainly between our politicians. It’s because there are stkes with those real debates. People don’t want to have to stick their neck out. They go out of their way to not take a stand on things. I think TV’s happy to let them do that as long as they get their one-liners and outrage and Donald Trump saying whatever he wants. Nobody’s risking anything, and you end up with these people who are all preaching to the converted. There’s a whole other book or documentary to be made about the effect television’s had on our political process today.

VINYARD: Which these debates, and the presidential debates with Kennedy Nixon, were a big part of.

GORDON: But they’re as much a part of the media aspect as they are part of the actual politics. It’s much more about the media, I think, than the politics.

NEVILLE: The kind of civility that used to be part of politics where you, as a member of the Senate or congress, were meant to work with people from across the aisle.

VINYARD: What a concept!

NEVILLE: Now, the media has jumped on everybody. The news cycle is 24 hours a day. If you do anything that’s out of step, it’s almost like a test of your loyalty. You’re constantly being kept in check by an endless, screaming news cycle and blogosphere that don’t allow you to do anything that’s not in lock-step with everyone else. You end up with two armies of people who can’t think for themselves.

VINYARD: They’re not even armies, because, like we saw with the Occupy movement and even the Tea Party, they’re very quick to abandon their cause at the slightest unrest.

GORDON: I didn’t see that in the Occupy movement.

VINYARD: It’s not more muted now than it was?

GORDON: Oh, it’s certainly more muted. The abandonment of their position was when they were rousted by the cops. People stayed there a long time. And what it did was it kept it on the front page of the news for much longer than many other items. I thought it was a victory.

NEVILLE: When you look at the stakes in 1968, we have the same stakes today.

VINYARD: Maybe moreso.

NEVILLE: But we all pretend we don’t. Back then, people were willing to blow up…if you look at the (Symbionese Liberation Army), and you look at the Black Panthers, and you look at the kind of extreme things that smart, educated people were doing because they saw this as truly about the destruction of the country. That’s such a distant memory today, because people ahrdly want to give up their Starbucks coffee for any kind of a political statement. It just feels like nobody appreciates the stakes, and I feel that everybody, the politicians, the media, and business, they all profit when everybody feels like nothing’s at stake. “Everything’s fine, just move on. Keep shopping, people.”

VINYARD: Is it easier to keep people complacent and comfortable now than it was in ’68, with iPhones and what have you?

NEVILLE: Well, distracted certainly. And things like getting rid of the draft was the other thing that took the stream out of the youth movement.

VINYARD: It kept the middle-class safe.

NEVILLE: Yes, basically. “Let the poor people fight the wars, your kids are fine!”

VINYARD: This will play on Netflix, right?

GORDON: Theaters, then Netflix, then PBS.

VINYARD: A lot of young people are going to discover this on Netflix, probably, with no knowledge of who either Buckley or Vidal are. What would you want them to think? There’s the natural instinct to take a side in the debate, which I think we just do as people no matter what movie we’re watching, fiction or documentary, but I think you guys are pushing something broader in terms of provoking debate.

GORDON: I want them to demand to see something more like this on networks today. It’s a naiive thought, but I want them to say, “Hey, wait a minute. I hadn’t thought of it all as fluff, but it is fluff, and where’s the content? Where’s the beef?!” That’s what I’d want, in the broader sense.

NEVILLE: The other thing is to remind people that this film’s actually pretty funny.

VINYARD: It played great at SXSW.

NEVILLE: It’s kind of a comedy that becomes a tragedy. I don’t want people who know nothing about this to feel like it’s taking medicine. I think it’s more like reminding ourselves collectively that there’s a better way to be a society, that we all have some responsibility in that. You make those decisions every day with what you decide to watch and spend money on. We should ask for more. We should demand more.

VINYARD: Was it hard to punch up the film in structuring it and editing it and getting the music to make it more of an easier pill to swallow?

GORDON: These guys are highly entertaining. You can watch the raw debates, and it’s captivating and it’s hilarious and it’s full of drama. Then, you have Gore Vidal who says, “An untelevised life is not worth living.” So we have a wealth of archival material to choose from. We knew we wanted a classical-oriented score, because it was more representative of them. The things we were attracted to was more dance stuff, waltzes or ballet-score, stuff like that. It worked with them, ‘cause they’re kind of bobbing-and-weaving in the ring.

VINYARD: Even physically, with their body language.

GORDON: Exactly. It didn’t cut like butter, but it didn’t cut like bricks either.

NEVILLE: That’s a good line. Tell the editors that.

VINYARD: You got Kelsey Grammer and John Lithgow to read as Buckley and Vidal, respectively.

GORDON: They called us up and asked to do it.

VINYARD: Really?

GORDON: No, I’m kidding. *laughs*

VINYARD: In Kelsey Grammer’s case, you wouldn’t have surprised me.

NEVILLE: And he was perfect. As the Hollywood conservative, he was a perfect Buckley. Lithgow knew Gore and was a liberal, so he was a perfect Gore.

GORDON: We knew we had those articles they’d written and writings of their’s about the debate that took us into their inner thoughts, so we knew we wanted to get that in. We started by trying to get soundalike ovices, but that would’ve ended up being distracting, so then we thought let’s go a whole other way. How far away from that can we get? Children, women, something like that. We were thinking mid-Atlantic, patrician accents, authrotative voices, and these actors kind of popped up in our minds. It works, because it helps you get lost. Their readings are so good, there’s so much space in them, that it’s not distracting that they don’t sound like the guys. You’re listening to the words and the thoughts.

VINYARD: I just read in (the press kit) that you guys did an interview with Gore that you didn’t end up using in the final cut. I assume that he was nearing the end of his life and there wasn’t much to go with. Was it tough maintaining objectivity, and even if you hadn’t known him?

NEVILLE: Nothing about not using Gore’s last interview had anything to do with the politics of it, or…

GORDON: His sharpness.

NEVILLE: He could’ve given us a good interview. The problem with the Gore interview was- he wasn’t in great shape- but he disagreed with the premise of the film, which is that you would ever consider Vidal and Buckley to be on a similar plane. The idea of equating them in any way was completely…

GORDON: Disdainful.

VINYARD: “You want to make a movie about when I stepped on an ant?”

GORDON: That’s basically the way he came at it!

NEVILLE: We did a three-hour interview, and he just wouldn’t give us anything. He called us “Buckley-ites,” just attacked us. And we felt it was unfair to have him have the final word and not let Buckley have the final word. I feel like everything you needed to know about how he felt about Buckley at the end of his life he had written in that obituary, that scathing obituary. He didn’t add anything knew. That’s why we didn’t use it.

But the whole thing about taking sides: we’re both liberal, but we didn’t want to make a movie to say, “This guy was right,” or, “That guy was right.” Because then you start to get into the arguments, and people start to say, “I don’t agree with that side,” and you’ve lost half your audience. We wanted to make a film not about the arguments, but about how they argue. Let’s step back, and not get caught up in this stuff that people debate every day, all the time already. Let’s talk about the way we talk, and the way we debate, and how we debate, and with whom we debate.

GORDON: It wasn’t so much a matter of…it’s balance more than it is objectivity. I don’t believe in objectivity. Seriously. But I believe in balance. You go through this movie being drawn to one side or the other side, and Buckley has the outburst and you dislike him for it, but not many minutes later, you see how it saddened him all his life. He had regret over it. You feel for that. He’s a human, with real emotion. Unlike Gore, who was a human without real emotion, you know? We were working to achieve that balance, which came pretty easily, almost on order. We had to do some tweaking. We would find everyone sort of leaning this way, and we’d add a scene in or take out something that would just help keep it better balanced.

VINYARD: One last question: have you spoken to any conservatives who’ve seen the film and gotten their reactions.

GORDON: Yeah.

NEVILLE: They said, “I’m glad you favored Buckley.” *laughs*

VINYARD: That’s excellent.

GORDON: It’s a real reward for us to hear each side coming and saying, “You favored our guy.”

BEST OF ENEMIES starts today at The Landmark in L.A. and at the IFC Center and the Lincoln Plaza Cinemas in New York. Look for it on Netflix later this year.