Since I first heard about it in college, I’ve been fascinated by the Stanford Prison Experiment.

For those who aren’t familiar with the experiment, here’s a brief summary: in the summer of 1971, psych professor Dr. Philip Zimbardo compiled 24 Stanford University students to serve as either prisoners and guards (12 each) in a makeshift, on-campus prison for the length of two weeks. It was meant to shine a light on the daunting psychological conditions of being imprisoned, or of being tasked to keep prisoners in line. While the guards weren’t allowed to strike the prisoners, they were given free reign in virtually all other respects, and the experiment rapidly degenerated into a horror show, with the prisoners ultimately undergoing immense physical and mental torture at the hands of their guards, who were, in reality, their peers and classmates. After a number of incidents, including two subjects quitting prematurely, the experiment ended only after six days, but the unique scenario and the extensive videotape footage they amassed gave it instant notoriety, and its been taught to psychology students for the past 40+ years.

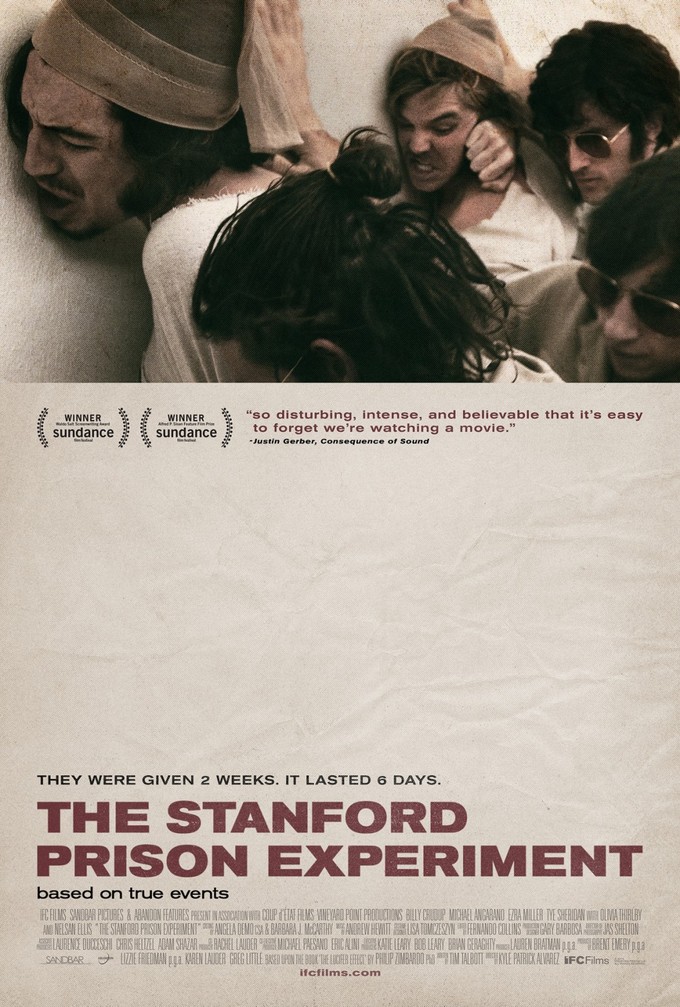

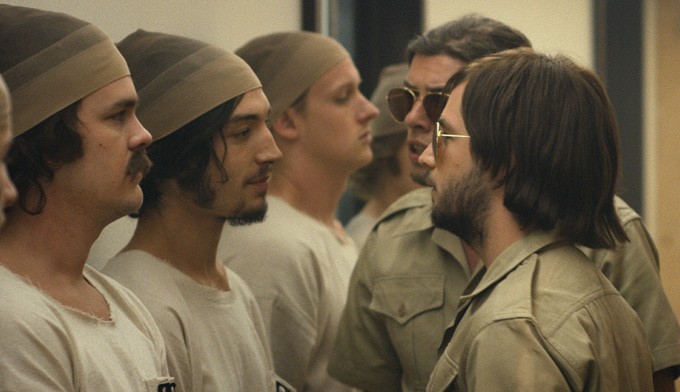

It’s not that hard to engage with this narrative on an intellectual level, but Kyle Alvarez’ film improbably manages to convey the weird, inconsistent moods this experiment must’ve evoked, and creates a believable environment of young, middle-class males, none older than 25, forced to undergo treatment similar to that granted to actual criminals. Violence was barred, and the prisoners were legally allowed to quit or fight back at any time, so the question then becomes why they submitted to such treatment in the first place, and Alvarez presents a very relatable scenario where these boys just kind of slowly, but surely ended up playing the parts they were expected to fill. Like so many Nazis said, they “were only following orders,” and Alvarez somehow keeps the humanity of these kids on the surface as we watch them do unspeakable, traumatizing things to one another. It helps that he has a cast of formidable young talents, including Tye Sheridan, Ezra Miller, Johnny Simmons, and a scene-stealing Michael Angarano, as well as Billy Crudup as Zimbardo himself.

Contrary to the tone of the film, Alvarez seemed like a cheerful, energetic guy when I met him, and he talked about how he cast the film, his relationship with Dr. Zimbardo, and his continued fascination with the complex psyche of the American male. We talked about the final moments of the film towards the end, so be warned:

KYLE: I’ve read Ain’t It Cool News since I was like 16. That woulda been like 16 years ago, I guess. I’m trying to think of the first year the site went up.

VINYARD: 1996.

KYLE: So it woulda been ’97, ’98 that I started reading then.

VINYARD: Are you from Austin?

KYLE: No, I was in Sacramento trying to find movie stuff online.

VINYARD: I was the same way, longtime reader of the site.

KYLE: Cool.

VINYARD: How did the screening go last night?

KYLE: It was good. I only made it there for the very end, but people stuck around. I was pretty happy. I think was like the first public screening we’ve had in L.A.. We’ve had a lot in New York and some festivals elsewhere, but it hasn’t really gotten anything in L.A. yet. I’m just excited for the movie to open, just ‘cause there’s a lot of people who haven’t seen it yet that live here, my friends and people I work with. It’ll be nice for it to be at the Arclight.

VINYARD: But you weren’t there for the whole screening?

KYLE: I didn’t get to listen on the reactions or anything, yeah.

VINYARD: Have you seen the movie with an audience?

KYLE: Yeah I did, I saw it at Sundance. Once I’ve seen it once or twice with an audience, I kind of try not to, because I find at that point, my job is to do Q & As and interviews, and the more you watch a film- I’ve never met a filmmaker in my entire life who watches his movie and goes, “Yup, looks pretty good!” There’s no version of that existing.

For me, it’s kind of like the cut of the film is reflective of the moment I was in, the deadline I was on, the tension I was under with producers and financiers and whatnot. You can’t look back. I don’t believe in the retconning of your films that a lot of ‘70s filmmakers do, going back and changing stuff. I feel like the movie is representative of the time, so in a weird way, I get peace by not watching that much of it, you know?

VINYARD: Was it tight, budget-wise and schedule-wise?

KYLE: Oh, god yeah. Weirdly, I had way more money that I’ve ever had before, which isn’t to say much. My other films were like a few-hundred-thousand-dollar movies. Way less resources in a lot of ways. It only costs more money because it was a more expensive movie. We had a huge cast, we had to build the set, we had to create the ‘70s look, that’s where the money went. The money did not go to more shooting days, or more equipment, or more crew, or any of those things that would make a shoot a little bit smoother. It was actually the hardest shoot I’ve ever done by quite a long shot. It was a really, really tight-budgeted film.

VINYARD: I heard a lot of the cast joking last night about how it was kind of a jovial mood on set, and they were joking around a lot, even though you had to hammer this out in- what was the shooting schedule?

KYLE: Schedule was tight. Minimum of 10-12 pages a day, most usually 13-15 a day. It was always just running, running, running, but my goal is to always shelter the cast as much as possible. I feel like a lot of people have a lot to lose when you’re making a movie, but when you’re shooting, the only people who really have anything to lose are the actors. I mean in terms of their humility, I don’t mean lose financially or anything like that. They’re the ones who have to go in front of a camera. No one’s going to be criticizing my edit, or my score, or my pacing or tone or anything like that while you’re shooting a movie, but the actors have to go and try and do something real.

Especially on this movie, where there is that potential to be that method-y, like aggressively acted film of like everyone trying to up the machismo, like David Ayer’s take on it. Not that I have a problem with that, by any means, but I was determined to work against that, and try to make it be a good experience. ‘Cause most of these guys, once we cast them and casting came down to the wire, most of them knew each other! Most of them had known each other for years and years.

VINYARD: That was a total coincidence?

KYLE: Yeah, mostly. In some cases, I knew that these guys had worked together. Like I knew Johnny Simmons and Ezra (Miller) had worked together, and Nick Braun had worked with both Ezra and Johnny and also Michael Angarano, I knew these guys had all worked together. But I didn’t know Logan Miller and Thomas Mann were like childhood friends, or that Keir (Gilchrist) and Logan were roommates. Those things, you just don’t really know.

The good thing is that if I tried to push them to be that thing, that really like aggressive, angry thing they were representing- you hear these stories of people going to military training and all that stuff to sort of amp up the testosterone- I just felt it would be there no matter what, so let’s just try to work against it. I think for the guys, it was a pretty fun set for them. I wish it had been more fun for me, but when it came to them I had a great time. Not that it wasn’t fun for me, but I could never really be in the moment. I always had to be two moments ahead. It can be a little frustrating by the end of it all.

VINYARD: It speaks to how well you cast the movie that they were able to keep up that kind of mood in such an intense mood with such heavy subject matter.

KYLE: To me, the audition process was twofold for a lot of the guys. It was like reading and auditioning and stuff, but a lot of it was just sitting down and talking. A lot of people, when you’re in your early-20s and late-teens- our youngest was Tye (Sheridan), who’s 17- you’re sort of reaching that stage…we wanted people who had worked on camera before. We didn’t want newbies. You’re talking about people who were child actors, who were probably acting maybe because they said they liked it, or maybe because their parents said they would like it, or whatever it might be, but now they’re reaching the age where they’re gonna choose if it’s something they actually wanna do.

So for me, it was about spending time with these people, and trying to understand, “Why is it you’re doing this? What is it you like about doing it, as opposed to when you were a kid? Do you really want this to be part of your professional life? What about it is it that you like?” A huge part of it of course was talent, but moreseo on this film, because it was an ensemble, it was sort of about “Why do you want to be there?” Because most of these guys were going to have to spend days without much to do, other than standing around, or doing jumping-jacks and push-ups all day long. We wanted to make sure they wanted to be there.

VINYARD: One guy who I recognized from his child actor days was Michael (Angarano). He was definitely the one whose performance I wasn’t expecting out of him, based on his earlier work.

KYLE: With that part, with the “John Wayne” (his character’s nickname) part, it’s a really big part, and it reached the point where it was like, this has to be an audition part. I’ve known Michael. I would’ve cast Michael in something in a heartbeat. His talent is unquestionable, but the part was so specific. There were so many wrong ways to do it, and I certainly saw so many auditions that did it the wrong way, so with Michael, I needed to see it. He was shooting THE KNICK at the time in New York, and he took like half a day or whatever and just taped it and sent in the tape, and it was like, there it is. Like I’d been looking at the wrong things, and for a while even going, “God, is the character just wrong, like the wrong approach?”

Then you saw that tape, and it all totally works, it’s going to work. For me, at that point, I couldn’t even think of anyone else. It was part seeing it, and part- the real guy who took on that accent and stuff was sort of a bigger guy, more of like a California surfer-y kinda type, very sort of bro-y, but I thought if you did that on film, if I really cast a really tall, imposing guy, you wouldn’t buy the psychology of it as strongly, you know what I mean? Just sort of like, “Oh, they’re just kinda scared of him actually.” With Michael, instead, I told him, “It’s all your personality. It’s not in your physicality at all.” It just sends the message of the movie a little bit clearer.

VINYARD: He has a very friendly, affable presence, especially if you’ve seen him in other stuff, so that gets you a lot deeper.

KYLE: Well, he did such a good job outside of the accent, only like three or four scenes. With Michael, when we were doing it, everyone on set was kinda like, “This is really great.” He was doing something so specific and bold, and everyone was sort of really excited about it.

VINYARD: One of my favorite moments in the movie is a quiet, non-dialogue scene when the prisoner gets paroled and makes eye contact with Michael in the hallway. That, to me, in this very simple, dialogue-free sequence, kind of gets at what this experiment revealed and what it did to these kids in a very concise, powerful moment.

KYLE: That was one of those days where we were shooting so much that day, where like I go back in my mind and I don’t even remember shooting it. I think we just did one take and we were like, “That was good, that was great, awesome, okay, we gotta move!” It was just a one-shot thing. I knew we didn’t need any coverage on it.

I gotta give Tim (Talbott) some credit for that. He wrote that scene. You forget sometimes, because when you are shooting so intensely, it becomes about the pages, and getting through the pages, which in turn becomes about getting through the dialogue. The challenge of any indie film or low-budget film is to always remember that more of the film is going to live in those moments than is going to live in the dialogue moments, in a lot of cases, depending on the film. I tried, the best I could, to remind myself that those moments were going to be really important, and a lot of them landed on Michael. Even when Ezra is doing push-ups, there’s a zoom on him that we didn’t even plan.

We actually shot on an old camera from the ‘70s for the security camera stuff, and when we were just shooting that stuff, we’d run the RED behind it just to see what we could grab since we were rolling anyways. There’s a handful of moments in the movie that just came from having the camera there and telling the operators, “Zoom in on that,”, or, “Pan that up,” and the actors or so unaware of the camera, that you find exciting stuff. I can understand when people can, like if they were shooting this right now, they’d do it with a really long lens from across the street, ‘cause it creates a different sense. I’ve never really done that before.

VINYARD: You were replicating stuff that they shot in the original experiment, which was on video.

KYLE: That’s why there’s not a lot. It was very expensive. They were sort of these quad, 3/4 things. This is ’71. We didn’t get the same exact thing. I believe it was literally the same camera, not the model, but the same body they shot NO on, the Pablo Larrain film they shot all over the world, ‘cause I think there’s only so many retro-fitted ‘70s cameras that record digital. It gave this great look. People have walked by that security camera footage, and they’ve gone, “Is that footage from the original experiment?” It gets blurry. We even taped up photos of all the original experiment around us, and I think someone’s reps came around and they were like, “Who took those photos? They’re great!” And we were like, “No, that’s from the experiment.” So there were moments where we felt like we re creating something authentic.

VINYARD: I remember one shot when Ezra’s breaking down, and he starts saying, “Stop messing with my head!” I remember that directly from the footage.

KYLE: Ezra was actually listening to that right before. He would hand me his headphones, and then we’d start rolling.

VINYARD: You can feel it.

KYLE: When he’s like, “I’m burning up inside!” that’s right from the clip. For me, it wasn’t about copying it, but hopefully taking inspiration from it. Somebody told me last night that they were so happy those final interviews were in the movie, because we remember them so well. Anyone who’s seen the documentary or watched it in class, it triggers this thing.

VINYARD: And they’re recontexualized, after having seen all that.

KYLE: Originally, I think I wanted to use those actual interviews, but I’m always weirded out when true stories cut to the real people at the end of the movie. I remember when RUSH did that, and it was like, “I didn’t really need to see the real guy to know that they got the makeup so right.” It was sort of like, “Why are we looking at that?” In some cases, I guess it makes sense, but in this case…we didn’t really cast the kids to look like the kids, because otherwise we would’ve been so limited. I don’t think people would’ve even connected to this character, or figured out who was who, or that kinda thing.

VINYARD: You did work closely with Dr. Zimbardo though. How early on in the process was he involved?

KYLE: Long before I was. The producer, Brent Emery, got Phil. Phil had been saying no to projects in the past, or previous versions had fallen apart, and I guess 10, 15 years ago, Brent reached out to Phil, talked to him a lot, convinced him, then brought Tim in. Tim and Phil worked closely together to write the script. Tim was writing the script at the same time Phil was writing Lucifer Effect, so they were digging up all the old research, and all the old documents and photos and everything. That’s when a lot of the heavy lifting was done, I think, in terms of presenting things, and what was changed and what wasn’t.

I think that’s the hard stuff. How do you take six days of recollection and data and events, hour-by-hour blow-by-blows, and try and reduce it? I think the first draft was something like 300-something pages or something, ‘cause Tim was like, “I’m just gonna put everything into it, and just see where we land.” And then it was like, “Oh, we landed at 320 pages!” I have that version of it. “Let’s start narrowing it in.”

And even the version I got still read a little bit broader, because I think it was being written for a bigger budget at the time. In the original script, you followed each person. You saw everyone in montage, each person going in. I think the attitude they had was more like, “Let’s shoot everything, and then find the movie in the edit,” which you can’t do on the kind of schedule and budget we did. That’s when I started encouraging Tim to sort of narrow it in. “Let’s just follow the one guy in. Let’s just see him, and then we’ll cut, and all the guys will be there already, and we’ll just have to trust the audience to fill in the blanks,” and that kinda stuff.

Phil was part of the reason I wanted to do it, to have his signing off on it.

VINYARD: My last question is a little bit of a softball: what is your personal history with the project? What’s your fascination with the experiment?

KYLE: I wasn’t one of those people who was like, “Oh my god, I’ve always wanted to do this movie.” The script came to me, and I liked the script. I always joke every time I finish a movie that I need to make a movie that has women in it. Because my first film is one guy in every frame of the movie, my second film is one guy in every frame of the movie, and then this film, it’s like this is the ultimate men-and-movie thing. Maybe there’s some weird, latent thing.

I am fascinated by, and my three movies do this and it’s not super deliberate, breaking down the conceptions of masculinity, like this idea of how men are supposed to behave versus how they really behave or how they really want to behave. I do think that’s sort of similar. That was part of what I said, even having gone from doing two comedies and doing this, the throughline is that this is about male psyche and trying to understand that. Even the way I worked with the actors was trying to work against some things about the male psyche, the way male actors can be, and trying to make a film that takes it so far that it actually becomes kind of sad.

At the same time, I just think I was really excited about casting it. I was really excited about shooting in a hallway for this whole time. It was a combination of all those things. As opposed to my previous films, they were more intensely personal, like “I wanna do this because this story is telling this.” I didn’t have any personal history with prisons, or prison reform, or abusive guards, or anything like that, so for me, it was just the combination of all those exciting things I thought it would be fun to take on.

VINYARD: Like with Michael’s casting, I think approaching it like that and letting the comedy sort of seep in helps make the darkness a lot more pronounced. It hits you a lot harder, as opposed to if it were 320 pages and it took forever to get in there, then the tragedy would just be amped up and built up, and it would ultimately be diffused a little bit.

KYLE: That was one of the reasons I put Michael in the part. He understood the comedy of it. By comedy, I don’t mean like ha-ha kinda comedy.

VINYARD: TAXI DRIVER is a very funny movie!

KYLE: *laughs* Exactly. He understood that there was an absurdity there, and that the absurdity had to be kinda fun, as opposed to what a lot of the guys did coming in- which is understandable, it’s probably what I’d do too, I mean I’d never act, but…they came in, and they were like, “THIS IS WHAT YOU’RE GONNA DO!” and blah-blah-blah, they’re angry. But Michael’s thing was more, “Fuck you all.” He had that kind of bravura to him, and I was so glad he brought it to set and that it cut together well.

When you step back, the movie’s fuckin’ weird. It’s a bunch of guys in potato sacks and stockings on their heads, and a guy with a bad, fake southern accent yelling at them and making them hump each other. It sort of occurred to me, “At any point, is someone gonna stop me and go, ‘This is ridiculous,’?” But it kinda works, so I’m grateful for that.

VINYARD: I love that the film ends on that note. Even Michael’s character, who’s causing this much drama- even when you see him before that final clip, he’s always sort of smirking about it, asking if they’re still getting paid- and then at the end, he says “I was running my own little experiment.”

KYLE: *laughs* And that guy really said that, and still kinda does. I find him fascinating.

THE STANFORD PRISON EXPERIMENT opens tomorrow at Arclight Hollywood and IFC Center in Downtown NYC, and will be available on VOD starting July 24th.