A BEAUTIFUL NOW, dir. Daniela Amavia

It’s Romy’s birthday. She’s a 30-something professional dancer who has a performance that night, but has asked her estranged best friend, David, to come to her house beforehand to celebrate. When he doesn’t show, she locks herself in the bathroom with a bottle of champagne and a gun; we can surmise this is the last straw for this apparently lonely, depressed woman.

When David finally gets there, he discovers Romy locked away, rambling and half-mad, clumsily firing off her gun in random directions. Panicked, he calls four of Romy’s old friends, including her ex-fiancee and his model sister, who promptly head over and try and extract her from her self-created confines. She shows no desire to come out of the bathroom, but she insists that their presence behind the door gives her comfort, so they stick around, and discuss with one another how they arrived at this precipitous point. Meanwhile, poor Romy is trapped in her own head, going over her childhood, her past relationships, and her crushing defeats in a mad whirlpool of memory fragments and schizophrenic commentary. As we learn of her friendships, romances, and failures, we learn that both Romy and her current situation have more going on than meets the eye.

Since I was a kid, I’ve been a huge fan of films that enclosed a bunch of characters within a single space for the course of the duration. GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS, MY DINNER WITH ANDRE, and 12 ANGRY MEN were obviously the ones to beat, but films like THE BIG KAHUNA, TAPE, and CUBE also made huge impressions on me. There’s something about that play-like immediacy mixed with the filmic styles of people like Sidney Lumet and Vincenzo Natali that can make these films a very particular experience, which, of course, makes the performances and the script 100% vital to the film’s success.

Unfortunately, the “longtime friends reunite after a long time and experience emotional catharsis” aspect of the film isn’t its strongest suit. As the group drinks, relaxes, and reveals each of their secrets to one another, their interactions feel more and more like artifice, and rarely tie back into the central narrative. They come off more like detached, witty archetypes (the slutty one, the gay one, the foreign one) than as deep, well-shaded characters. Thankfully, in the end, there’s an explanation for this, and their apparent disconnect to Romy makes more and more sense as the film goes on.

But what makes this film powerful, haunting, and deeply personal are not Romy’s friends; it’s Romy herself.

Director Daniela Amavia presents the narrative through Romy’s first-person thoughts and half-coherent narration, which creates an abstract pastiche of memory that makes the film feel deeply personal and intimate. This is an attempt at telling not only the story of a life, but a sort-of self-portrait ripped right from the consciousness of the protagonist. We see things out of order, just as she’d remember them. We spend more time with some memories than others, just as she would. And just as she does, we experience all this over the course of a few minutes of her life (one of the film’s most inspired touches), as we rarely recall moments from our lives in real time. I’d get so sucked into Romy’s psyche that cutting to her friends bantering outside the bathroom would bum me out; I just wanted to get back to that nose-close intimacy with Romy to get to the heart of whatever led her to lock herself away with a bottle and a revolver.

A huge part of that fascination with Romy has to do with the central performance by Abigail Spencer. You may know Spencer from her TV appearances, such as on MAD MEN, RECTIFY, and BURNING LOVE (where I first noticed her), but here, tasked with basically holding down the entire movie, she does revelatory work that makes Romy into a complicated, believable woman. It would be easy to dismiss this as a movie about “a crazy lady who tries to kill herself,” but it takes mere minutes with Spencer’s Romy to know that there’s much more going on than that, and I was dead intrigued to dig into her backstory to reverse-engineer her suicidal impulse. She occasionally devolves into aimless muttering, hitting similar notes as Cate Blanchett in BLUE JASMINE but without the safety of the comic undertones, and I found myself paying close attention to grasp every word of her rambling despite it’s incoherence. We see her in relationships with several men, and her behavior with each of them says volumes; we all act differently with different people in our lives, and watching that disconnect build and eventually overwhelm her is thoroughly real, affecting, and believable, thanks to Spencer’s efforts. She may be selfish, destructive, and very possibly crazy, but Spencer doesn’t let us dismiss Romy for a second, which helps keep us on the hook for the entire film.

Romy’s love for dance is a crucial aspect of her personality, and Spencer and Amavia work to press that on the audience. Spencer, a flexible, formidable dancer herself, is surrounded by talented stage dancers in abstract, visually ambitious sequences showing bodies in motion as a form of self-expression. As someone who knows (and cares) next to nothing about contemporary dance, I was nonetheless hypnotized by these scenes, and they help create an tangible sense of Romy’s emotions and mindset without uttering a single word.

There’s a great, haunting soundtrack by Johnny Jewel, philosophical yet ultimately coherent editing by Adam Mack and Valdis Oskarsdottir, and very deliberate, meticulous production design by Cindy Chao and Michele Yu. Collette Wolfe and (particularly) Cheyenne Jackson shine in their supporting roles, but this is ostensibly a one-woman-show, and Spencer blows everyone else off the screen with her brave, deeply wounded performance.

Director Daniela Avia was previously an actress, most notably in the CHILDREN OF DUNE miniseries for what was then called Sci-Fi, but she shows a visual sense and a grip of performances that blow many other first-time filmmakers out of the water. Her script isn’t as airtight as the presentation; the scenes with Romy’s friends talking without her lack the edge and impact of Romy just sitting there in her bathtub playing her own life out in her head, but that’s way harder to pull off than having a bunch of actors saying, “Hey, remember that time when…” There’s a lot of emotional, deeply complex stuff going on in this story, and Amavia and Spencer lead the way in creating a sad, human, and illuminating film out of it.

I’m glad Ms. Avia has found her calling, and I’m looking forward to her next film, particularly if it’s as ambitious and emotionally open as this one.

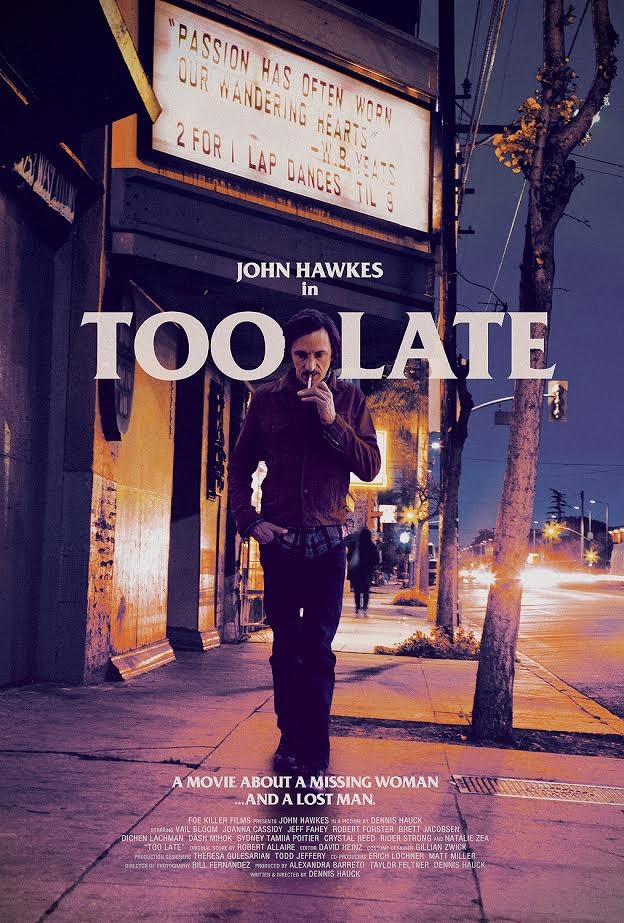

TOO LATE, dir. Dennis Huack

I’m sure many of you remember the slew of Tarantino imitators that came out of the woodwork after PULP FICTION. Some of those films worked in their own right (THINGS TO DO IN DENVER WHEN YOU’RE DEAD, Danny Cannon’s underseen PHOENIX), some blazed through via sheer style and excess (THE BOONDOCK SAINTS), and some were just downright lame (MAD DOG TIME), but there was no question that they were all greenlit primarily due to PULP’s massive crossover success (at the time, the highest grossing independent film ever made). It’s 20 years later, and times have changed; you can make a stylized movie about wisecracking, pop culture-savvy underworld types without being immediately compared to Tarantino, and there have been a lot of examples to sand away the direct comparison.

But director Dennis Hauck has done something remarkable with TOO LATE. He’s come closer than most, possibly the closest ever, to straight-up copying Tarantino in its superficial elements, namely its non-linear narrative, its casual, deadpan violence, and its chapter-like structure. Yet his film is so inventive, ambitious, clever, and shockingly elegant that it feels more unique and less like Tarantino than basically any of his imitators, not to mention other easy comparisons like Altman or Paul Thomas Anderson. Hauck’s approach was simple: create five interlocked scenes that would each run the length of a reel of 35mm film, similar to what Jarmusch did in STRANGER THAN PARADISE. However, his script, cast, and mindblowing cinematography create an intricate patchwork that is far greater and more significant than the sum of its parts, and, oddly soon after INHERENT VICE, feeds us another L.A.-set detective story that hits hard emotionally, intellectually, and aesthetically.

A lot of the film’s juice comes from its narrative surprises, so I’ll only skim the surface. Dorothy (Crystal Reed) is hiding in the mountains above Hollywood, and is clearly desperate and frightened. She calls private dick Sampson (John Hawkes), who happens to be nearby; the two met briefly years earlier, but whatever transpired has obviously allowed Dorothy to trust this guy unequivocally. She may have seen something she shouldn’t have at the strip club where she works, and asks him to protect her. From there, Sampson gets pulled into a snake pit of scuzzy L.A. types, including a crooked businessman (Robert Forster), his consigliere (Jeff Fahey), his emotionally unstable, nudity-friendly wife (Vail Bloom), a Lennie-and-George pair of dim-witted drug pushers (Dash Mihok and Rider Strong…yes, that Rider Strong), and a southern-fried snake-charmer named Skippy (Brett Jacobsen).

Let’s get the obvious aside: the cinematography in this film (as I mentioned, shot in 35 mm) is nothing short of amazing. We’re talking CHILDREN OF MEN, this-needs-to-be-studied-in-film-school level work. The film is (seemingly?) comprised of only five shots, but the camera is constantly moving, invisibly composing gorgeous image after gorgeous image while the narrative plays itself out in individual parcels of real time. We jump from location to location, character to character, and interaction to interaction, but unlike films like BIRDMAN: OR (THE UNEXPECTED VIRTUE OF IGNORANCE) or GRAVITY, there are no digital seams to be noticed; save for one or two digital touches and some pitch-perfect splitscreen, this is all in-camera amazingness, nailed by a very enterprising director, his equally formidable (and unbelievably first-time) D.P., and some very game and capable camera ops.

But none of that would matter if the film didn’t deliver as a narrative, and by gum, it does. From its opening scene, it gives you just enough information to get you invested while making a promise that it will never settle into the expected, and will keep you constantly surprised and curious as the film lets on. The film keeps this promise. I’m not just talking about, “Oh man, I just shot Marvin in the face”-type sudden violence and non-sequitur black comedy. I mean a central mystery that’s seemingly plain-as-day on the surface, but reveals a sea of secrets and relationships underneath. I mean supporting characters who refuse to play to their archetypes, and possess such color and humanity that you feel like you’re getting glimpses into a richer backstory instead of mere constructs for a particular scene. I mean a combination of sincerity and old-school 70’s-style cool, a depicted world where love does exist and people do care about each other, but always have one eye on the exit sign in case their selfishness takes hold.

The one element that keeps these various narrative threads together is John Hawkes’ central performance as Sampson. Now, I know that it may be too soon to say whether Hawkes’ Sampson is right on par with Elliot Gould’s Philip Marlowe, and it’s unlikely his loose-suited, quietly driven shamus will inspire the same level of iconography and pop cultural impact. But I will say that watching Hawkes hop around L.A. in his loud 1980 Trans-Am, take a fairly hearty amount of physical pain, and verbally tap-dance around all who come in his path took me back to that first time I basked in THE LONG GOODBYE, and not in that “I’ve seen this before” kinda way, but more in that “this motherfucker’s that cool” kinda way. Whenever we think we’ve got this guy’s number, he does what Marlowe did with that revolver at the end of GOODBYE, and surprises us with a new chink in his armor (hold on, this guy can sing?). Given the vast range of roles he’s taken over the years, I thought I’d seen pretty much all Mr. Hawkes had to offer; this was a rare time when slowly figuring out I was wrong put an increasingly-wide smile on my face.

None of the supporting cast get the kind of showcase Hawkes does, but several of them are given huge emotional arcs to play, sometimes within a matter of minutes. Reed has an welcoming innocence, but her Dorothy is no L.A. washout, and knows how to talk to men of various threat levels and when to keep her cards close to her chest. Bloom has a jaw-dropping beat that would never work in a million years if she didn’t sell her character’s unhinged, cooped-up hysteria. The two pairs of male sleazeballs, Forster & Fahey and Strong & Mihok, are believably slimy and funny, particularly Strong’s irredeemable, self-important shittalker. Dichen Lachman is strong and sexy as a resourceful, but catty stripper, Sydney Tamiia Poitier (a.k.a. DEATH PROOF’s Jungle Julia) is a stylish, but morally compromised housewife, and Nathalie Zea has a heartbreaking turn as one of La-la-land’s many discontented rich girls. Last but not least, Hauck’s frequent collaborator Jacobsen kills it as the enigmatic, elusive Skippy, with a silkiness that somehow puts your guard down while never quite putting you at ease. They all contribute to the great, living universe of the film, and each of them somehow manages to balance the technical challenges of these amazingly complex shots while simultaneously depicting believable, empathetic characters.

It may seem like I’m laying the hyperbole down thick, and I suppose I am, but describing my reaction to TOO LATE in any other terms would just be dishonest. I see a lot of movies, and almost always have a moment where I say, “I wish this would happen,” or, “I wish there was more/less of that character.” This film somehow gave me everything I wanted from it without once settling into formula or familiarity. Seeing it last night was such a delight for me I almost feel biased in writing this review; when a film feels like it was made for you, how do you communicate its strengths to those who don’t share your exact sensibilities? All I can do is implore you to check it out for yourself, and judge whether you agree that Huack’s film belongs in the pantheon of great L.A. detective stories.

TOO LATE will play once more at LAFF next Wednesday, June 17th. Non-Angelenos should keep an eye out for whenever this one makes its way nationwide.