By Jeremy Smith

Born on September 13, 1976, Colin Trevorrow grew up during the Amblin Age of filmmaking. He’s a child of E.T., POLTERGEIST, RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, GREMLINS and all those “escapist” films that blended crackerjack storytelling with groundbreaking special effects as a means of inducing awe in audiences both young and old. When they worked, these movies weren’t just entertainments; they were glimpses of a fantastic world. And they were so utterly convincing that a whole generation of filmmakers flocked to film school to learn the discipline of light and magic.

Trevorrow had the same dream, and, thanks to a good deal of pluck and one celebrated indie film (SAFETY NOT GUARANTEED) that drew the attention of difficult-to-impress folks like Brad Bird, he’s been given the Golden Ticket to the dream factory. But here’s the kicker: his first assignment is to reinvigorate Steven Spielberg’s dormant JURASSIC PARK franchise with the ambitiously-titled JURASSIC WORLD. In other words, he’s got to out-trick the master magician – or, at the very least, meet him on his level.

This is both an honor and an impossible task: there’s no replicating the Brachiosaurus reveal from JURASSIC PARK; we’ve seen CG dinosaurs and humans share the frame dozens of times. So how do you inspire audiences anew? Trevorrow’s approach is an interesting one: he acknowledges the faded wonder of the park’s creatures as a means of lulling the characters (and moviegoers) into a false sense of security. But while families cuddle with docile dinos in petting zoos, we learn there’s a new, genetically modified badass on the block. It’s called the Indominus Rex, and all it wants to do is kill everything in its path. It’s a variation on the old “lack of humility before nature” theme; these scientists just keep making bigger mistakes, which lead to greater calamities. Once JURASSIC WORLD hits its third act, Trevorrow unleashes a relentless onslaught of carnivorous mayhem. It’s basically DESTROY ALL DINOS, and, truth be told, that’s a fairly irresistible proposition.

I had the opportunity to chat with Trevorrow last week about the development of the screenplay (from Sayles’s draft to the contributions of Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver), as well as the myriad challenges of reopening Spielberg’s Jurassic romper room. He’s a sharp fella equipped with the proper amount of humility considering the property with which he’s been entrusted (hear that, Dr. Malcolm?). But he definitely doesn’t lack for confidence, which, quite honestly, is what you want from someone who’s attempting to recapture the joy and terror of one of cinema’s most successful franchise. We also discussed his days interning for SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE, lobbying for the animatronic Apatosaurus, and whether he’s tight enough with Spielberg to talk about 1941.

Jeremy Smith: It must be surreal for you today. You’ve made a film that comments on the burden of branded spectacle, and the necessity to keep making more of the thing that people love. And you’re doing interviews so close to the amusement park (Universal Studios Hollywood) where all of this is being perpetuated. How does this make you feel?

Colin Trevorrow: I don’t know how we got away with it. I’ve been talking to a lot of people today, and we’ve been talking about this [subject] a great deal. We’ve certainly made a film about the corporatization of America, and particularly the corporatization of our childhoods, and the things that we love, and how much of the joy has been sucked out by the need to make extensive profits. To me, this movie has these themes in it because it’s what we were dealing with when we wrote it. We had a movie with a release date that was far too close to the time when it was being conceived and written. That represented our amazing ability to make the same mistakes again and again, no matter how many times we learn the lessons – and that felt like something we could make a dinosaur movie about.

Jeremy: This idea of delivering thrills, but also poking fun at the sequel aspect, this makes me think of GREMLINS 2.

Trevorrow: (Laughs) You’re the second person to mention GREMLINS 2 today.

Jeremy: I’m pissed off I’m not the first! (Laughs)

Trevorrow: I need to rewatch this.

Jeremy: It’s fantastic. But that’s a film that goes much more haywire as a comedy, in a good way. You definitely don’t do that. You’ve got to give them the goods, but you also want to acknowledge what it is you’re doing.

Trevorrow: What you’re saying really was the goal of the film. It is a self-aware movie, and I am a very self-aware person. If I was going to give myself a compliment, it would be that my self-awareness levels are very high. I’m aware of my strengths and weaknesses, and I’m aware of the movie’s strengths and potential weaknesses, and I felt like the mission, if we chose to accept it, was to make something that knows what it is and what it’s trying to be and what it can’t be. It’s nearly impossible to make a movie that does what JURASSIC PARK does, but the greatest victory would be that, in the kind of delirium and misdirection we throw at people when you think we’re making some kind of meta-commentary, suddenly you realize, “Wait, this is the real thing!” You get to the end, and you realize it’s the real thing. That’s what we were trying to do.

Jeremy: How aware were you of the John Sayles script before you took this project, and were you also aware of the drafts by Mark Protosevich and others? Did you ever read these scripts?

Trevorrow: I did. You know, I didn’t see it as a geek on the internet in the past; I saw it as the director of JURASSIC WORLD looking back at what had come before. I read Rick and Amanda’s script when I got in, but I hadn’t seen those others. I think it was a couple of months later that I said, “Let me go back and look at those. This could be interesting.” And I’ve got to tell you, man, that [Sayles] script was fascinating in a lot of ways. There were a lot of things I loved about it. It was properly bonkers. In a way, I aspired for our film, in its fearlessness and willingness, to go there. I think it took certain risks that came from Steven – and I know those writers were translating ideas onto the page. This idea of a guy who can train raptors, it exists in a certain way in that script as well. Have you read that script?

Jeremy: A long time ago, yes.

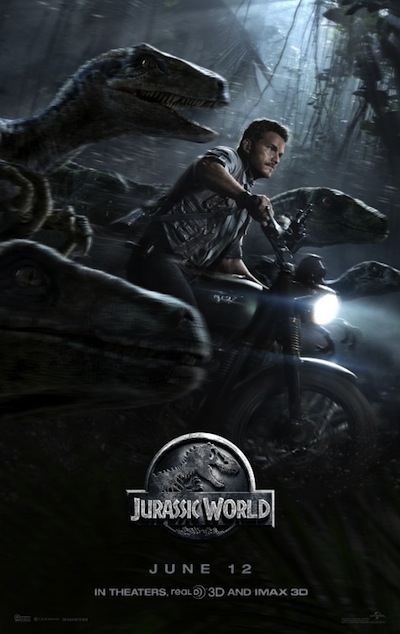

Trevorrow: Obviously, the headline, the thing people pull away from that is “Oh, my god, human DNA in a dinosaur!” But this character, Owen Grady, there is a form of this character in that movie, and there is a form of this character in Rick and Amanda’s script. And when Steven Spielberg has an idea that he feels that strongly about, that he goes through so many very talented writers… we’re talking John Sayles, William Monahan, Rick and Amanda… these are not hacks. For all of these people to attempt to interpret one of those ideas, and for him to continue to insist there is something there… he’s right! So our goal was, “Alright, let’s get to the core of this, and find out what he’s so fascinated by. Let’s find out why he needs to see an image of a guy on a motorcycle surrounded by raptors like they’re on a foxhunt” – even though that wasn’t in any of the other drafts, that was something we found. Steven Spielberg has ideas that become iconic for a reason. At first blush, they might sound crazy, but they’re not.

Jeremy: I’m going to take a shot in the dark here. You interned at SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE back in the day, and I’ve heard Steven is a huge fan of the show. He’s known to drop by several times during the season. Did you ever have a backstage encounter with him as an intern?

Trevorrow: I didn’t at all. I am a big SNL geek, too, and more than a lot of things that people are geeks about, to the point where I engineered a way to direct the host of THE TONIGHT SHOW on the SNL stage. That was one of the highlights of this whole process for me. When Pratt was on the show [in September], I went to that show. When I got there, I noticed they had a pass for Steven next to mine. I was like, “Oh, that’s cool! Is he coming?” And they said, “No, that’s there every night just in case he decides to come. We have it there every week.” So that gave me a career goal. I want to reach a point where they always have a Colin Trevorrow pass for me at SNL.

Jeremy: Getting to pick Spielberg’s brain, and we’re talking about someone who defined much of my childhood and, I’m sure, yours… can you think of one thing that stands out? One thing you learned from him that perhaps you didn’t expect?

Trevorrow: The amount of time, and the richness and depth of that relationship was something I had not anticipated. I thought it was going to be a bit more cursory, but we really dug in and built something together. The one thing I observed the most about him is that he has an ability to just know innately what the audience wants to be seeing and what they want to be feeling at any given moment. To have that, to be so in tune with that, and to be able to step away from a role as a filmmaker and turn around and sit in the seat as an audience member… that’s very difficult to do. That’s something I tried to train myself to do, but there is nobody better at it than him.

Jeremy: Have you gotten to be good enough friends with him – and I say this with all seriousness and love for the film – that you feel like you can ask him about 1941?

Trevorrow: (Laughs) I would never be so presumptuous to say that we’re friends. He has yet to invite me on the boat, or anything that his friends get to do. So, no, we haven’t had that conversation.

Jeremy: Darn. Well, please let me know if you do. I do want to ask you about the animatronic Apatosaurus in the film. That is by far the most moving scene in the movie for me. It really works.

Trevorrow: Thank you. I intended it to be.

Jeremy: Are there any other animatronic creatures in the film?

Trevorrow: The raptors that are in the squeeze cages when Omar Sy and Vincent D’Onofrio are talking, those were maquettes that allowed us to put digital skin on them. They were kind of a halfway point, where he could interact with them and touch them, and you could see him touch them. Those were the only two scenarios that we used anything close to an animatronic. Getting the animatronic Apatosaurus was one of the few battles I had to wage, because they certainly aren’t cost effective and ILM says “Look, we can create something that looks completely real” – and they can. But it was important to me. And I’m a firm believer that that scene wouldn’t have worked nearly as well had we not got John Rosengrant and Legacy Studios to come in and build that animal.

Jeremy: Well, you got me with it, so thank you for doing it. You know, we’ve talked about Spielberg as a mentor figure for you, but I’m curious, as you move forward with your career, what other filmmakers are major influences for you.

Trevorrow: When I look at directors that I really admire, two that stand out to me – and it’s really about their careers and the choices they made – are Peter Weir and Richard Donner. Both of them… it’s not as easy to identify a film by either of them, because each of them are so different. But they’re so solid and deft and well-handled, and I think it’s just the variety of the kinds of stories they told is always something that I admired. And I’d put Steven in there, even though his films are easier to identify; you know a Steven Spielberg film based on the techniques he uses. But I just love cinema. I love Woody Allen and Truffaut and all of the films Coppola made in the ‘70s. Just being a fan of film makes me highly motivated to tell different kinds of stories, and not just do what I think would be a very easy move right now, and fall into making new versions of movies that I liked as a kid – which I have a feeling are going to be part of it because I had an incredible time doing this. But I do want to tell different kinds of stories, and the next films I’m going to do are original screenplays. They’re a little bit smaller than this in scope, but I think the stories are just as big, and they’re just as challenging creatively. I hold myself to very high standards as a filmmaker and a creator. I have a feeling I’ll fail a couple of times, and that, to me, is the most interesting thing about the filmmakers that I love: the movies don’t always connect. Some movies are better than others. I challenge you to think of a filmmaker who just nailed it every single time out. I think a lot of that comes from the fact that these people gave themselves the latitude to take risks. I think that’s how they ended up being great.

Jeremy: And sometimes those failures, those mutts… those are the ones we end up loving the most in a weird way.

Trevorrow: Yeah.

Jeremy: Colin, thanks so much for the time, and best of luck on your next movies.

Trevorrow: Alright, man. I hope you enjoy my future failures. (Laughs)

Jeremy: I look forward to all of them!

JURASSIC WORLD stomps into theaters on June 12, 2015.