Hello ladies and gentlemen, Muldoon here with our weekly peek at the many different positions on a film production. Each week here on MEET THE CREW we chat with the folks who work long and hard crafting our favorite films, but don't typically travel on the press tours or get slapped on the covers of magazines. We've chatted with Production Designers, Line Producers, Storyboard Artists, and this week we've got ourselves a talented Film Editor, Arthur Tarnowski. Arthur has cut films like Eric Bana's DEADFALL, Jay Baruchel's GOOD NEIGHBORS, and recently Paul Walker's BRICK MANSIONS. Arthur has been cutting films, trailers, and more since the mid 90's and has seen it all - so rest assured he's got some incredible stories in the Q&A below! Before we hop on in, I would like to thank Arthur for taking time out of his busy schedule to chat with us today - it's very much appreciated.

ARTHUR TARNOWSKI - EDITOR

As an editor, what are your principle duties? I realize “you take footage and craft a movie out of it” might be an easy answer, but I’m curious about the things beyond the surface level. How would you describe your job? How early are you brought on to a given production?

Each film has its own set of challenges, but as you mention, an editor’s job is to take the footage and try to craft the best possible story from it.

The first thing I do is read the script, then have a few conversations with the director to get his or her take on what the film is about and use these ideas as a guide when cutting the individual scenes. Often the director or producers will ask if I have ideas or suggestions about the script before shooting starts. A common question at this stage is: if they cut a given scene, will the story still work Much depends on if it’s a director I’ve worked with before. If I have, we’ll usually have talked at length before the shoot happens. The editor will sometimes cut a scene in a completely different way than the director had intended, and that’s neither good or bad, but it definitely opens the film up to possibilities. Which is why it’s good that the director and editor not be the same person, although some directors edit themselves and do a great job. Once we start shooting, I review the dailies shot the day before, just to imprint the images in my mind; if I feel I might be missing something I will see it then, after that it’s just cutting the individual scenes and really getting to know all of the material. I usually start cutting just after shooting begins so that a week or two after the filming stops we can have a rough cut to look at before we start shaping the film. It’s also important to let the script go once the editing has started, let the material you are discovering everyday talk to you. The film is different than the script so you have to adapt to that. If at one point you get lost, the script can be like a roadmap to get yourself back on track.

It’s often said that editing is like writing the final draft of a screenplay, but people don’t often realize how much editing can impact a film. Editing can change the timeline, the point of view of the protagonist in the film, or re-order scenes or create scenes that were never shot or scripted in order to tell the story in a more effective way. This happened on GIBRALTAR (aka THE INFORMANT), a French film about a man who’s life changes when he becomes a drug trafficking informant. After we’d assembled the film we found we needed to give the opening some action and establish context for the story. So we created an opening sequence with maps, stock footage, newspaper clippings and photos. Supported by a great musical cue by the film’s composer, Clinton Shorter (District 9, Pompeii), the sequence succeeded in illustrating the dark world where our main character was headed. It wasn’t in the original script but was very helpful in getting us into the story.

Editors deal with many kinds of issues. There’s a lot of decision making, picking the right takes, or making sure you haven’t forgotten or missed a shot for a given scene – even though you might have an astronomical amount of footage and dozens of takes (as with an action film like BRICK MANSIONS, where routinely a scene is covered with three or four cameras). However, it can also be the opposite; sometimes you feel you don’t have enough material to make the scene work as well as it should, and you have to request a reshoot. It’s tricky because when you ask for something like that it means money and time for the production, which is usually something they don’t have. I always first talk to the director about this type of issue (or anything else) as he’s the one you’re working for – it’s his vision you’re helping to fulfill. But diplomacy is key. On my first film, I was so eager to do my job that I just mentioned in passing to one of the producers that I felt we were having a lot of continuity issues. They almost fired the continuity person, who called me in a panic wondering what the heck the problem was. Little did I realize at the time that continuity was an issue on just about every film and that it was really my job to deal with it. With experience, you actually realize how continuity is less important than you think; if the performance is good and the scene is working, you can get away with a lot.

What duties would you consider are the most rewarding for you? There’s clearly a reason you do what you do and part of me hopes it’s not all for the money. On the flip side, what are some tasks that absolutely need to get done that might not be fun - things folks might not think of when they imagine a rock star editor. I’m thinking about dailies, logging clips, working with VFX, complete scene overhauls, etc...

I often say I’m very lucky that my job is not a job – it’s a passion. Once, when reading my kids bedtime stories, I told them I do the same thing at work, only there I get paid for it. And hopefully people don’t fall asleep when I’m done! I’ve always loved movies: I grew up on Star Wars and Star Trek, reading Starlog magazine and collecting soundtracks. I’m a huge James Bond fan. I worked in a video store, and as an usher in a movie theatre (where I spent the summer of 1987 watching a 70mm print of THE UNTOUCHABLES over and over again)… and this is where it brought me. So honestly, every part of my job is pretty awesome; be it putting together a dialogue scene that really works, cutting an action scene that is exciting (like the snowmobile chase in DEADFALL), or editing performances by actors like Max Von Sydow and Omar Sharif, who are a part of film history. Being an avid soundtrack collector, I enjoy putting temp score on the films I cut – and even though temporary music can really be a pain for composers, I find it can also be a benefit as it allows everyone to be on the same page or at least have a point of reference when talking about the film’s music. That being said, I love it when the composer forgets our temp and comes up with new and original ideas that really make the film come together even more strongly.

It’s hard for people to understand how you can spend twenty weeks or more in a dark room, editing and re-editing the same two-hour film. There can be a lot of pressure, especially on bigger-budgeted films. If a film isn’t working, people will point to the editor and say: “ So how do we fix this?”, and you must find the solution. It can be tough. It’s important that the director and the editor be on the same page, and it often means having big discussions about the film’s structure, about which scenes should stay in or be removed, etc. And if you have disagreements, you have to be diplomatic about it.

VFX heavy or green screen scenes can have their share of editorial challenges as well, as you’re not always sure at that stage exactly what will be happening behind the actors or if the timing between the foreground and background action will be right. For that reason, we usually plan on tweaking the cuts once those shots are completed. It’s sometimes quite exhilarating to see a VFX heavy sequence come together after months of seeing it without the CG or plates integrated… it’s like a whole new film. I usually react similarly to the sound mix; it adds so much to the finished film.

The flip side of having any passion is that it can sometimes consume you. Ask anyone who works in film or television (and not just in post-production). Family and life in general often take second position to the project you’re working on, and you have to be aware of that. The hours and days go by very fast to the point where if I tell my wife that I will be home in half an hour, she’ll then ask me if that’s an “editor half hour”, meaning she knows I’ll be back in two hours.

Do you edit solo or do you have assistants? If you have assistants, what are some tasks they might have to handle in order for you to do your job? On that same note of who you work with most, what positions/departments do you typically lean most on to ensure you can best do your job while fulfilling the director’s vision?

On every project, I have assistants; how many depends on the budget and time. In Montreal – where I work mostly – editors tend to be more self-reliant. And I always feel that the assistant should do more than just digitize or prep the material and sort out the technical side of things. I often encourage them to cut some scenes (which we look at and discuss) or to prep temp VFX shots, or do some sound design work on scenes that require it. The problem is that budgets are constantly squeezed, so the assistants usually already have an overwhelming workload and often don’t have the time to do these things. I find it’s good to have another set of eyes who know the material like you do. An assistant may look at what you’ve done and have a helpful suggestion, so I like to look at my edits with them and get their feedback. By contrast, in the early 90s I worked for two years as a camera technician in castings for television commercials where I was specifically told not to speak and just do my job. I’ll never forget a grueling four-day casting marathon where the director, François Girard (THE RED VIOLIN), was trying to decide between the final 2 actors for a commercial. After hours of deliberating, he turned to me in front of a half dozen ad agency creatives and asked who I would pick. I told him who and why; he agreed, and that was that. I really appreciated him asking for my input, so I always try to do the same with the people I work with.

As for the members of the crew I work with the most to help get the director’s vision: that would be the visual effects crew, the sound designers (who might even give me sound effects and rough mixes as I’m editing to help our offline cuts feel more complete when we do test screenings), and of course the composer or a music editor – but as I said above, I tend to like to do the temp score myself.

Did you go to film school? Either way, what are your thoughts on the importance (or lack thereof) on going to college for film?

I think we each have our path. For some that means university, and for some it’s working on sets and learning your craft there. Both have value. I graduated from the Communications Studies program of Montreal’s Concordia University, specializing in film. I really enjoyed university; it allowed me to learn about filmmaking with people who were passionate and whose objectives were not yet part of a business plan. You got to watch classic films on a movie theatre-sized screen – projected on 16mm and 35mm film – and then get into great discussions that led to a deeper understanding of them. You got gear to shoot your film, but you learned some discipline about dealing with deadlines, working with others, and writing and shooting a film when you didn't necessarily have the time or the means to do what you set out to accomplish. Making short films in school was an amazing experience and allowed me to cut and splice actual film on a 16mm Steenbeck editing machine. This is the period just before non-linear, computer based editing became the norm. Cutting on film meant that when you had an idea, you had to go searching through large rolls of film to find the shot before you could select it, cut it out of that roll, and then edit it in where you wanted it to go. Every decision was time consuming and needed to be thought out.

One of the biggest benefits of going to film school is collaborating with people who are as passionate as you are and who, in the years following your studies, will become friends and work collaborators. You create a network, with friends like Saul Pincus, whose feature film debut, Nocturne, is making the film festival rounds, or Maziar Bahari, who's also a filmmaker, and whose eventful life was recently the subject of Jon Stewart’s directorial debut, Rosewater.

I should also mention that I learned a lot about film from years of managing a video store, which on top of having all the mainstream films, also had a great foreign film section. Not only could I rent the films for free, but I could have them playing in the store while working. I stopped counting how many times I watched Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan or The Spy Who loved Me. Time well spent.

How did you come to be where you are now, editing features? In other words, what path led to you to the editor’s chair?

In university I discovered a passion for editing, which led me to cut my own films and eventually those of some of my fellow classmates. I then worked many jobs peripheral to the film industry: video store manager, movie theatre usher, college teaching assistant, casting technician, on set production assistant – you name it.

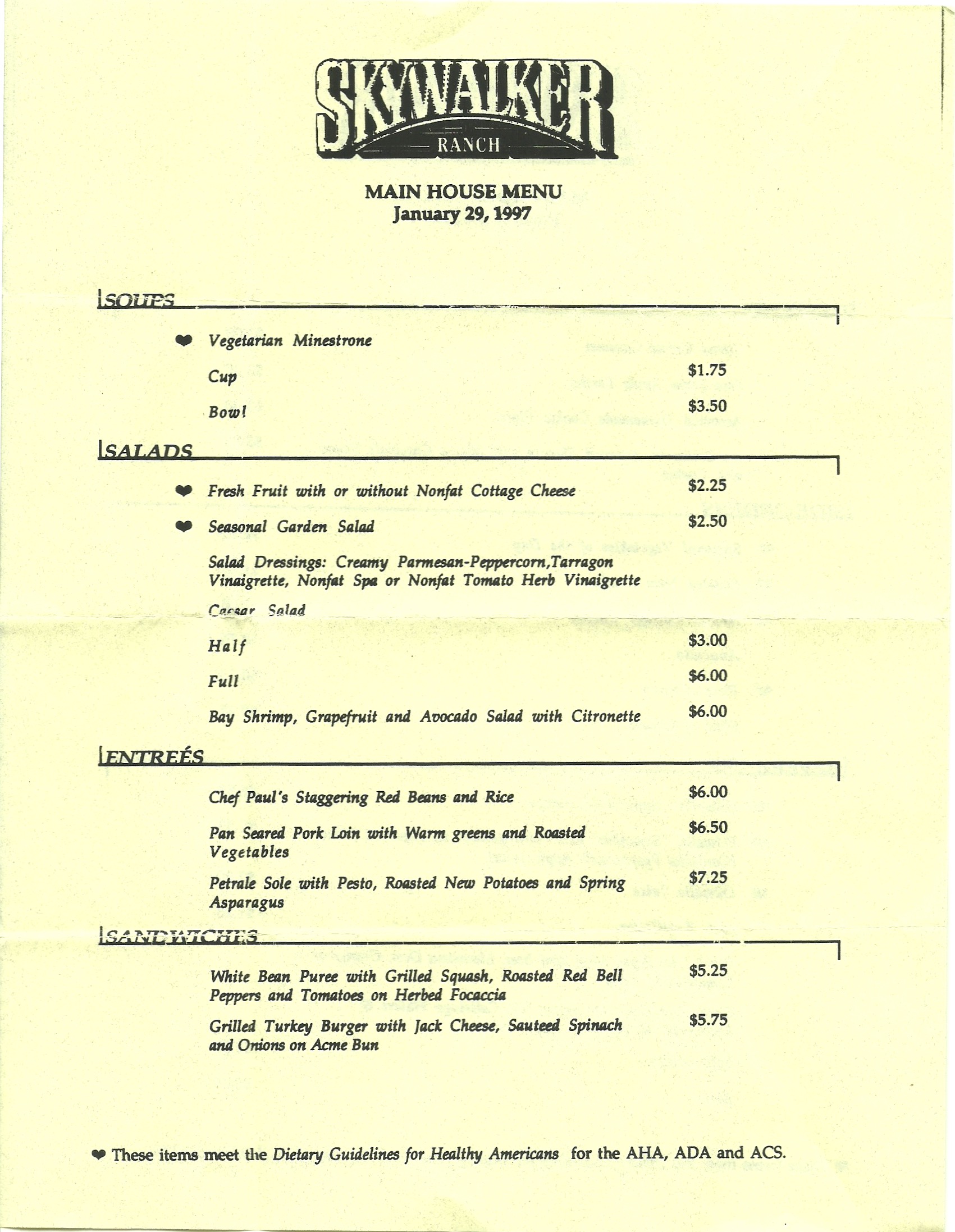

One day, while helping direct traffic on the set of a tv commercial, I nearly got run over by an 18-wheeler. That day, I said to myself: “I am an editor”, repeating it over and over in my head like a mantra. And during the next few months, two critical things happened. A friend invited me to San Francisco, where he was working for a week. That was near Skywalker Sound. I knew of a family friend who worked at Skywalker as a dialogue editor, and I thought I’d pay her a visit. When we walked in, I imagined I would hear R2D2 beeping in the corridors… and I did! The sound editors were hard at work, about to mix of the Special Edition of THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK, and had I been there a few days more I could have attended a private screening for the crew of the STAR WARS special edition in the Skywalker screening room… So I missed out on that, but I came from there thinking that these super nice sound editors were just regular people who happen to do the kind of job that I would love to do. Suddenly this dream of a career in the film business didn't seem so far away.

After that, I came home spent all of the money I had at the time (1000$) on a three day Avid editing seminar. And I did something else. I cut a 20 minute James Bond video tribute – which played very tight, much like a 20 minute trailer – for all the films from Dr. No through to Goldeneye ( the latest Bond film at the time). This became my editing demo reel, and as much as I thought my student films were good, this Bond montage was something that some local producers responded much better to.

But when a potential low-budget feature was looking for an editor, they still felt I didn’t have enough fiction experience. So I suggested they hire me for a week, and if they liked my work they could hire me for the whole film; if they didn't think I was up to it, they didn't have to pay. After that week, they hired me, and my film editing career had begun. I did lots of TV movies and television series, which led to feature films. Being a bilingual (French and English) editor in Montreal gives you many of opportunities for work. Montreal editors also have the luxury of going from film to television, to commercials to documentaries or also in my case to editing-conceiving trailers. We aren’t obliged to stay in one medium or genre as is more the case in other parts of the world. I find Montreal a very creative place because it’s a real mixture of European and American sensibilities.

Were there any individuals who helped you with that first ‘big break?

I'll always be indebted to Stefan Wodoslawsky, a producer, who gave me my first job. He was very creative and showed me how much editing could influence a film. At first, he didn’t want to hire me (see above) – but their post-supervisor, Pierre Theriault, took a look at my resumé and noticed that I had managed a video store which, coincidentally, he had managed previously. That convinced him to suggest me, to convince others like Wodoslawsky to give me a chance. Pierre and I have worked on many projects since. He’s a great post-supervisor and a good friend.

There are others as well. A director named Paolo Barzman – with whom I worked in television in the early 2000’s and many times since then – brought me onboard the feature EMOTIONAL ARITHMETIC (starring Susan Sarandon, Christopher Plummer, Gabriel Byrne and Max Von Sydow); the film was retitled AUTUMN HEARTS when it came out in the U.S. and it was the closing film at the Toronto International Film Festival a few years ago. Paolo also introduced me to his friend Paul Hirsch (CARRIE, STAR WARS, THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK, FERRIS BUELLER’S DAY OFF, MISSION IMPOSSIBLE,…), an amazing editor and person who inspired me before I even knew what editing was. Another important individual is Kevin Tierney, a producer, whom I met when I cut a trailer for one of his films (BON COP, BAD COP). We got along and he suggested I meet his son, Jacob, who was about to direct a comedy called THE TROTSKY. I ended up cutting two films with Jacob. He is also a good friend, incredibly talented, and we’re hoping to do another project soon.

What’s a typical day in your world like while you are working on a feature?

Typically I get to the cutting room just before 9am. If we’re shooting, I’ll look at the material that has come in and sometimes review what I cut the day before. Then I'll just get into cutting the new material. If we’re on a deadline, I'll eat lunch in the cutting room – which I prefer not to do because it’s important to clear your head every few hours. Usually we finish around 7 or 8pm, but in crunch times we can easily go much, much later. When shooting wraps, I work with the director. Some like to be there all the time, while others will give notes and come back the next day. Both ways work. Most of the time, it’s quite a solitary exercise… it even feels that way when the director is present as you're trying to fix cuts or adjust scenes. But an editor’s day is never done. Inspiration doesn’t keep to a schedule, and some of my best edits came to me while driving home or in the shower. You are constantly thinking about the film.

Out of the films you’ve cut, which three hold a dear place in your heart as an altogether great experience?

It’s a difficult question to answer – in my mind, the experience matters just as much as the final result. People in the business will tell you that it’s the people you meet on the job that make things memorable. Which is why the first thing that comes to mind is an action-adventure TV series I edited from 2000 to 2002 called LARGO (based on a Belgian comic book series, LARGO WINCH). Although co-produced by Paramount Television, it was barely seen in the U.S. but did well internationally, where the comic book had a following. On top of editing this project, I got to direct second unit in Paris and New York. In New York, we shot aerials of the city with a pilot named Al Cerullo, who among other things, had shot the plates for SUPERMAN: THE MOVIE. He was a great guy and it was an awesome experience. I also made lifelong friends and worked with some great filmmakers, including the aforementioned Paolo Barzman – with whom I'd later work on EMOTIONAL ARITHMETIC – and an editor-director named David Wu, who had edited most of John Woo’s films from their Hong Kong period, such as HARD BOILED and THE KILLER. David mostly directs but returns occasionally to edit, and not only his own films, but with John Woo on RED CLIFF and others. He was so much fun to work with and it’s always pleasant when people you admire for their work also happen to be great human beings.

These next three features also left a lasting impression:

DEADFALL, directed by Stefan Ruzowitzky, was a Fargoesque winter thriller with a great cast that included Eric Bana. The film was shot in Canada but then we moved to editing in Austria where the director lives, and then L.A., where we finished the film. The director and producers were great. On the L.A. leg, I had the pleasure to collaborate with Dan Zimmerman, who is very talented and from a family of famous Hollywood editors – not to mention a great guy. The composer on the film was Marco Beltrami (I, ROBOT, WORLD WAR Z), who did a fantastic job on the score and is also a really nice guy. I’m happy with how it all turned out, and we had a great premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York. During the time editing in L.A. and thanks to a writer-producer friend, I got to go to a DGA special event honouring Steven Spielberg, who told stories with a panel that included James Cameron and J.J. Abrams and was moderated by Michael Apted… a very inspiring night.

THE TROTSKY, written and directed by Jacob Tierney, was a slightly political Ferris Bueller-like comedy about Leon (Jay Baruchel), who thinks he is the reincarnation of Leon Trotsky, the Russian revolutionary. They say comedy is hard, but the whole experience on that film was pure joy. It was also my first collaboration with Jacob, who wrote a great script and just created this contagious energy on set that made it memorable for all of us. The film has a great cast and won numerous audience awards at various festivals and makes me laugh every time I see it. I often show excerpts when I give editing lectures.

WHITEWASH, directed by Emanuel Hoss-Desmarais, was a cross between CASTAWAY and FARGO. The film won Best First Feature for the director at Tribeca, and was produced by Luc Dery and Kim McCraw, who have already had two of their films nominated in the foreign film category at the Oscars. It was a great experience working with them and Emanuel, who has been a good friend for over twenty three years. We knew each other when we dreamt of making films while hanging out at the local pizza joint, and now we were working together on his feature debut. It was a challenge because large parts of the film had no dialogue, and we had to show the boredom and despair that sets in for the main character lost in the wintery woods while making sure the audience wasn’t getting bored themselves. This was helped in large part by Thomas Haden Church’s nuanced performance and the humour he brought to the role. While we were editing the film, Thomas came in to screen it with us and was happy with how things were going but was little underwhelmed and felt we hadn’t nailed it yet. At first we were a little surprised by his comments, but we went back to work and he was right. We tried a few radical things and it really helped make it better. It’s always good to be open minded, question and push things, it can only be beneficial for the film.

Other mentions:

EMOTIONAL ARITHMETIC, by Paolo Barzman, a touching human story with a stellar cast.

GIBRALTAR, a French thriller directed by Julien Leclercq featuring great French actors including Tahar Rahim (from the film A PROPHET).

THE RED TENT, a mini series shot in Morocco directed by Roger Young, a prolific TV director who also shot the pilot for MAGNUM P.I.

HENRI HENRI, from Martin Talbot, a feel-good French Canadian film which is a mixture ofFORREST GUMP, BEING THEREandAMELIE.

BRICK MANSIONS, an English remake of the French action film DISTRICT 13. It's the first feature directed Camille Delamarre, who edited TAKEN 2 and COLOMBIANA. Sadly, the film was also one of Paul Walker’s last before his tragic death in November of 2013. I met him twice during production and he really was the nicest guy.

Do you have any stories from the trenches? Like a project that called for some unconventional tweaks, like perhaps an actor broke a wrist midway through or got a black eye and re-shoots weren’t possible?

A couple of things come to mind, but unfortunately they’re not humorous anecdotes. On LARGO, as I mentioned earlier, I shot second unit footage of New York in November of 2000. We had already locked several episodes including the pilot which featured this footage. Then the tragedy of 9/11 happened, so obviously all our footage which featured the World Trade Center had to be removed and substituted. We had shot a lot of coverage of New York, so it worked out – but it was a very sad time. On the actual day of September 11th, 2001, we were shooting an episode in Paris, with a storyline which featured a terrorist who’s character name was Yussif Bin Hassan – a character name which was probably inspired by Osama Bin Laden. We changed the name to something which didn’t make you think about Bin Laden but allowed us to achieve a suitable lip match when re-recording the dialogue.

Another TV series I edited called 15/LOVE was about a group of child prodigies in a famous tennis academy. A terrible tragedy brought filming to a halt halfway through production. Two of our leads, Jaclyn Linetsky and Vadim Schneider, died in a horrible car accident on their way to the set. It was devastating. Production stopped, of course. After the initial shock, the families of the two actors and the producers decided to create an episode which incorporated the tragedy into the storyline. It was a tough time, and it’s very hard to watch that episode, just as it was difficult to put it together. But I think it was somewhat therapeutic for the cast and crew to do those scenes and it was a tribute to those young actors, who had so much to live for. The show went on for two more seasons.

If you weren’t involved in film as a career at all, what do you think you’d be doing with your life? What other professions out there seem like they’d be a good fit for you?

I always knew from a young age that film was for me, but my mom was a teacher, and I think I would have loved doing that. I would have loved to have become a doctor, to really be useful, but when I think of people who have influenced me in a positive way, there are several teachers in that group. Which is why I give an editing lecture every year at my old high school: it’s so great to see the spark in a student’s eye when explaining something you’re passionate about and they really respond to it.

We have an incredible number of filmmakers here in the AICN audience, some big, some aspiring – what advice would you give to both types based on what your experiences behind the screen? What are some things you wish more established directors would do, perhaps a trend or a workflow you see that ends with poor results. Across the board, what are some crucial mistakes you would tell (anyone really) to avoid, things that should be thought about in prep in order to ensure maximum efficiency without shooting yourself in the foot?

Every director has his or her way of working, and what’s good for one may not be good for the other. At the end of the day, the film will speak for you.

Editors are often seen as the last line of defense on a film with the classic line: “we’ll fix it in post!” In editing, you can do a lot of things, but the material you start from is the base and you can’t fix everything. It reminds me of a metaphor someone once told me. Imagine you have a huge stain on your carpet. You are upset, so you wash, scrub and clean it as best you can… for days! You finally get it to where it’s almost completely gone, and you’re pretty confident it’s invisible to most. Then someone walks into your house, and the first thing they say is: “Holy crap, what happened to your carpet, and what’s with that awful stain?”

David Wu always told me: “You can be the best cook in the world, but if you have bad rice, you will make bad food”. So my best advice is to write a good screenplay, work it, and re-write it until you’re oozing with confidence when you start shooting – this helps get your collaborators on board. It’s not easy. In terms of concrete advice, I have had the opportunity to edit several directors’ first features and luckily, a lot of them knew the importance of performance. You can have great frames and cool camera moves, but you need to really work with the actors, gain their confidence and push them – just as they need direction and a space to be creative.

I also prefer when a director doesn’t call “cut” too quickly and lets the camera roll after a scene is supposedly done; the actors tend to relax, as they often feel their work is finished – and you can mine some great moments, like that look they have as they wonder why no one has called “cut”.

In terms of actual technique, my work mantra stems from something David Wu told me once, in his great Hong Kong English accent: “You must always cut before the audience cuts!” Sometimes that actually means staying on the shot longer, and sometimes it’s getting out of a scene before it ends. You have to keep the audience surprised and strive to not make things predictable. Also, you should always plan the post schedule to give yourself some additional time, so that a week or two after you lock the edit, you can go back and do tweaks if you need to. The hardest thing is to see the film from a fresh perspective and have some distance.

Finally, during the edit and always before I picture lock a film, I will screen the cut without any sound. This allows me to really see if the rhythm of the piece is working and the individual cuts as well. It's a great way to notice things I might have missed; subtle mistakes which the sound may have covered up.

Lastly, what are you currently working on?

I’m currently completing a French film called RABID DOGS from a writer-director with a great eye named Eric Hannezo. The French title is ENRAGÉS. It has a great cast of French actors including Lambert Wilson (THE MATRIX RELOADED) and Virginie Ledoyen (THE BEACH). It’s a remake of the cult film by renowned Italian director Mario Bava, about a heist gone wrong (is there any other kind!), which turns into a kidnapping and then into a tension-filled road movie that keeps you guessing with several twists and action sequences along the way. Everyone involved is quite excited because it’s not the kind of film that is often made in France. Even though it’s a remake, it’s quite original, very cinematic and a real mixture of American and European cinema. It’s been joy working on the film with Eric, a very enthusiastic and talented director. The film should be coming out in France sometime in the next couple of months and eventually, I imagine, in the U.S. A trailer should be forthcoming. But in the meantime I’ve included the first images released from the film, I believe exclusively to AICN.

BONUS Scan Arthur thought might be fun to share (and I agree!):

Alright ladies and gents, there we have it - a fun and informative Q&A with a talented editor. I really would like to thank Arthur for his time, the in depth answers he provided were well beyond what I could have hoped for and I fully appreciate him sitting down to give each question a thoughtful response.

If you work in film or television and feel like shedding some light on what exactly your position entails, then please feel free to shoot me an email with the subject line "MTC - (Your Name) - (Your Position)." I'm not here to get scoops or dirt on anyone, simply here to educate and ask for advice to any of our filmmakers in the audience.

If you folks are interested in finding out what other positions on a film are like, then check out any of the links below:

Robby Baumgartner - Director of Photography

Thomas S. Hammock - Production Designer

Seamus Tierney - Cinematographer

Brian McQuery - 1st Assistant Director

Shannon Shea - Creature/VFX Supervisor

Christopher A. Nelson - Special Makeup Effects Artist

William Greenfield - Unit Production Manager

- Mike McCutchen

"Muldoon"

Mike@aintitcool.com

![]()