Julien Temple has been making music videos and movies about music for over 35 years. Aside from his work on fictional films like EARTH GIRLS ARE EASY and ABSOLUTE BEGINNERS (both of which have musical numbers), he's done documentaries on folks like The Sex Pistols, Joe Strummer, and The Rolling Stones, not to mention videos for everyone from Neil Young to the Scissor Sisters. He'd even tackled the subject of this film, Wilko Johnson, and his band Dr. Feelgood, in a doc called OIL CITY CONFIDENTIAL.

But he's never done anything quite like THE ECSTASY OF WILKO JOHNSON. His kaleidoscopic examination of the musician's battle with pancreatic cancer, and the unpredictable emotions that came along with it, is a deep, powerful rumination on death, disease, and keeping perspective on life itself. I adored the film, so when I was presented with the offer of interviewing Mr. Temple, I jumped at the chance to question the vet filmmaker on his psychadelic approach to the film, the process of actually making it, and of course, about Wilko himself.

VINYARD: First thing I want to talk about is your relationship with Wilko. How long have you known him? How did you guys meet?

TEMPLE: I saw his band when I was young, a kid, but I never met him until I did a film called OIL CITY CONFIDENTIAL, which was about the Feelgoods, in 2009 I think. So I met him then. I had a certain good feeling, because he’s a little bit older than me but we’d lived through similar times. He loved the Rolling Stones when he was a kid, and I started out (listening to music) about the same time. We both took lots of acid, went to India…you know, rock-and-roll, but also literally. I never knew he was so well-read and so interested in astronomy and things like this, things I find really interesting. So I didn’t share a surprising amount with him. That’s when I met him and became quite friendly with him, doing that film, because it kind of brought them back.

Dr. Feelgood, his band, were an important band that somehow got washed away by punk like some deluge swept everything out. Although they’d been quite instrumental in creating the pre-conditions of punk, they somehow got lost, and people didn’t really know who they were anymore. So making that film was very important in that sense, and it brought him back. He started playing bigger gigs, and there was a sort of renaissance for him. So we had a good connection. This film is very different, because I don’t think you need to know who he is to really enjoy this film. The fact that he is a musician who made a big difference both in England and in New York, in terms of the story of the music, is kind of irrelevant. It’s kind of a bonus if people want to find out who he was and what he did. There’s a lot there to find out. But in a way he’s just a man sitting on a wall, and he’s being told he’s gonna die, and he’s sharing what that feels like, which may not be relevant to people at this point in their lives, but at some point what he has to say is actually quite relevant to everyone, isn’t it?

VINYARD: One of the things I found powerful about the movie was that, as someone who’s relatively young and healthy, I was still able to empathize and able to at least think I understand what he was going through. He hadn’t been diagnosed when you shot the film in 2009, his diagnosis was later-

TEMPLE: No, no, that was later. He had a real kind of resurgance for a couple of years after the film, playing much bigger venues with this great band. His bass player is a really phenomenal player as well, so they were a really good band again. And then, probably three or four years after the film, this diagnosis happened.

I didn’t rush out and wave a camera in his face when I heard about that. I didn’t have any idea to do a film about it. Except after a while…he was given 10 months to live, and we were all really like, “Wow. It’s hard to believe such a life force is going.” But he refused to go! He kept playing, and playing, and after 10 months he was still playing, and he became a figure beyond the music in England. People in daytime TV were seeing him, and going, “Wow, this guy’s talking in a really interesting way about what he’s going through.” And his concerts became these strange events where the audience was crying, and crying, and waving goodbye. It was kind of an up energy, but the kind of sadness there was strange.

So that’s when I thought I should suggest that he might want to talk about what he’s going through, which he seemed to jump on. He loved that idea. There was nothing to think about. He was like, “Yeah, sure, come, and we’ll talk.” It kind of fell into happening, it wasn’t something planned.

VINYARD: He’s incredibly eloquent about what he’s going through, and like you said, he uses a ton of literary quotations and a ton of references to astronomy, but that never used to come up before you started filming?

TEMPLE: He was always fascinating. I didn’t know this about him, but when I did meet him, he could drop quotations in any conversation. He’d find a phrase that seemed to make sense. You wouldn’t neccessarily know where it came from, whether it was Chaucer, or Coleridge, or Milton, or Shakespeare a lot of the time. He has two things: an incredible memory, how he remembers all these sources, but also a knowledge of literature. He’s one of the seven early Icelandic speakers in England, which he learned so he could read Viking sagas in the original Norse. He’s very obsessive in some ways.

He’s got a strange-shaped head; I think he’s half-dolphin, actually, that’s my theory. It’s like some alien guy. Look at his head, he’s like a dolphin!

VINYARD: Obviously, he’s a fascinating subject, but what you’re doing in the film is, beyond the thematic ambition of dealing with death and something as loaded and deep as that, also visually ambitious. The editing style and the choice of film clips, stock footage, nature footage, time-lapse, and things like that that are incredibly striking, and the pace is relentless. Could you talk about your approach to the movie? Because obviously you had all the interview footage with Wilko, but then what led you to do the more surreal aspects of the movie, like him as Death walking around, the SEVENTH SEAL references, et cetera?

TEMPLE: I don’t know. I think there’s an irreverance in using those images that’s kind of a punk thing. Because it’s very simple for me to talk with a camera with one guy, you don’t need a huge crew, I felt very free. I was interested in making a film that pushed the boundaries of what you could do, which I’m always interested in, but I was quite free to do that here. That’s the only kick I get out of it, is doing something I hadn’t been able to do before. That’s really important to me, otherwise I don’t really enjoy it. I get really upset if I feel I can’t do that.

So this film was a chance. It was a different kind of subject. I had a feeling that I could make it while I was half-asleep. I’ve got this flat in London where I’ve got high ceilings, so I quite like lying there and letting thoughts float around. Then I gotta cut it while I’m milling away, which is a drag because you don’t walk enough. If you have a thought, you can get there, or find the bit…

It’s important in the process not to plan it too much up front. It’s important that you interact with the creation of it as you go along. So I’d be thinking of things he said to me, and let these really early cinematic images come to me, and see whether they connected with what he was saying. It’s great, you know. It’s really posible to do now. Youtube is great in that way, because you can find what you want, whereas when I started out you’d never be able to make a film like this. The range of references would take so long to chase down.

VINYARD: Let alone actually physically cutting them on a Movieola.

TEMPLE: Yeah, it wouldn’t be possible, really.

VINYARD: Did Wilko have any input?

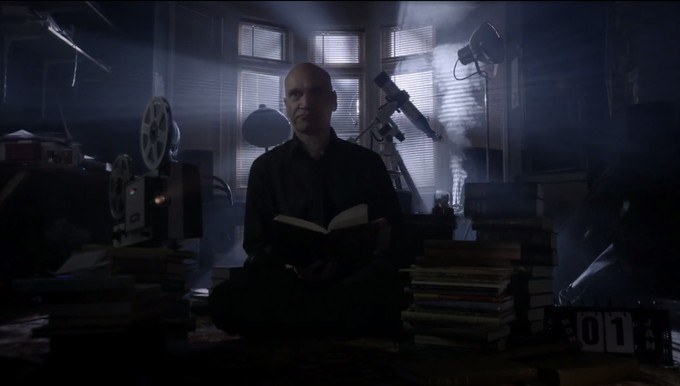

TEMPLE: No, he just turns up and does his thing; He never tells you anything to do, which is great. He hasn’t seen it yet, so I don’t know what he’ll make of it. I was saying in some interview he was like some Medieval saint, but he was also a dark monk, I can’t remember the phrase. How cantankerous and miserable he is as well. But all that went around the world was that he was a Medieval saint! He’s definitely not a saint. There’s a bit of a sinner there as well. It’s weird when…I think this film reflects what he was going through pretty honestly. But then you get into the media, and he’s getting called a Medieval saint. There is an aspect of THE ECSTASY OF SANTA TERESA, where you have this heightened response to the world around you. It’s a very religious thing perhaps. There’s something very spirtiual about his response to where he found himself. And weirdly, his popularity with people who didn’t know his music means people come up to him and they touch him like he’s some kind of saint, so there is an element of that. But he’s also rock-and-roll sinner as well as a saint.

VINYARD: There seems to be something cosmic about his refusal to do chemotherapy, which they said would have extended his life by two months, and he outlived that prediction without any chemo.

TEMPLE: Yeah. I think if he did what they told him, he may not have survived the operation. It is a magical story. It is something quite miraculous that he’s still here, especially when you saw him with this…thing in his stomach. In a way, i think people need therapy of some kind to come back from that situation. I hope the music will be enough. He’s all into showing off onstage, and his mad way of playing the guitar, and the fact that he couldn’t do that I think was hard for him for a while. Now he’s strong enough to do a show for a full show, so I think he’s gonna feel a lot better when he’s playing.

VINYARD: Obviously you had your own footage of him playing for the other documentary, but was it tricky finding the archival footage of Dr. Feelgood?

TEMPLE: It is quite hard to find, ‘cause there’s very little of it, so it’s kind of using the same footage in different ways. That was the trick. I was putting other film images on top of it, playing around with it. What I was proud of was finding Johnny Kidd & The Pirates, who are a really important band in the context of English music. In early rock-and-roll, there were only two or three groups who really meant anything in the English context, and Kidd was probably the main one. Obviously everyone knows that “Shakin’ All Over” song, but there are a lot of other great songs that they did, and they very much influenced The Who, and Pete Townshend. A lot of the great bands of that time were influenced by this guy, but everything about him had been lost. It was like Johnny Kidd is this kind of mystery man, there’s no imagery of him at all, moving image. Totally lost to history, this band. Our researcher found this footage of him in Northern Ireland, in Belfast. The guy with the patch walking around the docks, that’s Johnny Kidd. That’s the first time people have seen him, and he meant a lot to the music, so it’s quite great that we found that footage.

VINYARD: Did you have any trouble getting the rights to any of the film clips, like STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN or THE VIKINGS?

TEMPLE: The people who license THE SEVENTH SEAL wouldn’t cut any slack, but the rest of the people were really general. It’s a subject…I think this film can really help people, particularly people suffering from cancer. Wilko’s giving the money, if we make any money, to his charity, teenage cancer. That helped in a way to get the licenses, because they thought it was a good, positive thing to lend their film to us without charging too much money. Because we couldn’t have used it if they wanted too much, if they all wanted what THE SEVENTH SEAL wanted. There would be no film.

VINYARD: You mentioned that he did acid back in the day, and there are studies now that show terminal cancer patients who have experience with hallucinogens have a much sunnier outlook on their situation.

TEMPLE: I didn’t know that.

VINYARD: It’s fairly recent I think. That’s one of the things I was thinking about during the film, how the film almost resembled a hallucinogenic experience with all the editing, and lingering on things, “The world in a grain of sand,” and notions of finding beauty in different places, and the subjectivity of time.

TEMPLE: That’s one thing I did share with Wilko, was taking a lot of acid when I was a kid. I’ve always been aware that that has had an influence on my creative process. I did look at the whole thing in the context of the euphoria of an ecstatic religious experience, or hallucinogenic experience, or a visionary, poetic experience like Blake or Coleridge. Having to do with, not necessarily hallucinegens, but alternate states of consciousness. I wanted to not shy away from that. I do like the section where he talks about acid. I was trying to film the film in a way that held the clarity of that acid experience on that sea wall.

VINYARD: Very philosophical, very abstract.

TEMPLE: We’ve got kind of that vanishing points of the wall. Big sky, big clouds.

VINYARD: You see Wilko playing chess with Death, like in THE SEVENTH SEAL. Why the decision to make him the guy in the hood, the Death figure?

TEMPLE: Well, I think when you confront death, you are really confronting yourself as well. That’s part of the thinking of that. These were decisions I didn’t spend a lot of time…THE SEVENTH SEAL thing was a bit of a piss-take, really. He was surprised when I asked him to put the hood on, because I was wearing the Grim Reaper gear when asking him questions, and then I said, “Now you do it.” I think he found it funny. He’s got a great sense of humor.

VINYARD: And that chess board was great. Where did you get your hands on that?

TEMPLE: I’ve had that for a long time. It’s actually a replica that they used to sell at the British museum of this famous chess set that they found on a beach. They found the pieces in the sand in the Orkney Islands, which are really far north. It’s a Viking chess set. Lewis, the Isle of Lewis. It’s famous. Wilko knew it. It’s famous in England. He has a lot…a big part of him is the Norse mythology. He speaks early Icelandic because he wanted to read the sagas, so I thought that would connect with him.

VINYARD: You have some great footage of Daltrey in the movie, talking about his relationship with Wilko.

TEMPLE: Doctor Daltrey.

VINYARD: Was there anyone else that you tried to get, or wanted to get?

TEMPLE: I only got Roger Daltrey because this album (Going Back Home, which Daltrey and Wilko recorded together in 2013) was kind of a strange thing that happened. It’s funny to see him explaining (in reference to Wilko’s tumor), “It’s like an orange peel, it’s just kind of like an orange.” Elton John makes a genius appearance in it.

VINYARD: Sure. He actually gave him his award.

TEMPLE: He did, which was nice. I like that moment. I like the stick of, we call it “rock.” Is that rock? You get this candy like that at the seaside, like a stick of rock.

VINYARD: Did you go with him to Japan? Were you already filming him for the documentary at that point?

TEMPLE: I didn’t film that. I had some friend of mine film it for me. We couldn’t afford things like a trip to Japan.

VINYARD: But you already decided that it would be part of the documentary, you’d already made the decision by that point-

TEMPLE: To get it filmed, yeah. He’s always had a big connection with Japan. For some reason they like him. I think it’s the dolphin in him.

VINYARD: The timeline of the film is a little iffy with the calendar pages coming off, and I wasn’t aware that he recovered when I was watching the film, so I didn’t know whether it was the time before his operation, or that the 10-month period had elapsed, etc. Can you give me a more specific timeframe of when you decided to start filming?

TEMPLE: We started filming early last year, and he got the sense that he could have the separation in April.

VINYARD: You were already filming.

TEMPLE: Yeah, but we also used stuff from TV that he’d done before that. There were some other sources, radio interviews from earlier. So you do have him talking all the way through the period, although I didn’t start filming until about a year ago.

VINYARD: Would you ever want to do a follow-up to this?

TEMPLE: What, film him dying for real? Yeah!

VINYARD: End the trilogy.

TEMPLE: I intend to film the Sex Pistols deathbed, that’s for sure. It’s a bit like…we have this thing called 7 UP, where you film these kids every 7 years. It feels like that with the Sex Pistols.

VINYARD: Last question: you’ve moved back and forth from narrative to documentary quite a bit over the years. Do you have any particular affinity for one or the other? Do the aesthetics of one translate to the other and vice versa?

TEMPLE: I don’t think I make documentaries or fiction. i don’t think this film is a straight, down-the-line documentary. There’s fiction filmmaking in this film. I just see it as cinema, moving images that move people and tell stories. I’m not interested in kind of observational documentary, I don’t want to follow a guy around with a camera crew waiting for something to happen. I’d rather intervene and shape what’s happening around as a filmmaker, which is more of a fiction element, I suppose. I think really I’m interested in breaking down the notion that one is one thing, and the other’s the other thing. I was always drawn to films that seemed to do that. I loved the film of Jean Vigo, I think eh was the first guy to really take that documentary tradition of the Lumiere brothers and Melies. The position of using the ideas of surrealism and interior realities, as well as exterior realism.

VINYARD: Was there ever a time you shot a subject and you weren’t happy with the results? ‘Cause there’s always that risk.

TEMPLE: Yeah. I’ve shot a lot of things I’m not happy with. You have to move on, you know?

Trailer: The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson from Polite Storm on Vimeo.

THE ECSTASY OF WILKO JOHNSON is playing tonight at 6:45 at the Vimeo Theater in Austin as part of SXSW, as well as this Friday at 1:15 at the Alamo on South Lamar.