Papa Vinyard here, now here's a little somethin' for ya...

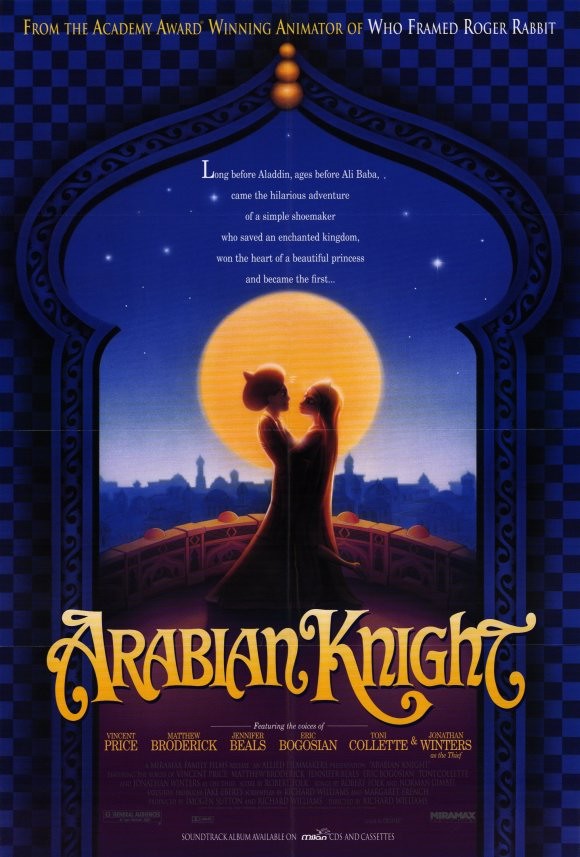

You ever hear of the movie ARABIAN KNIGHT? I wouldn't be surprised if you hadn't. It was an animated flick that came and went in the summer of '95. As the title would suggest, it had a vaguely Persian animation style that many found to be the highlight of the picture. Buncha celebrity voices on it too. Matthew Broderick, Jonathan Winters, Toni Collette, Eric Bogosian, Jennifer Beals, and Vincent Price two years after his death.

But unfortunately, the film closely resembled a recent Disney movie: the megablockbuster, ALADDIN. With the knowledge that many would write the film as a ripoff, Miramax dumped it into a few hundred theaters with a nonexistent promotional push. It wasn't even able to crack half-a-million at the box-office. As legend has it, the film was so forgotten, that the DVD was being given away for free in boxes of Fruit Loops.

But wouldn't you know it; the film, originally titled THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER, is actually one of the most influential animated films of the 20th century. It was painstakingly crafted (by hand, as was the norm) over the course of almost 30 years, by legendary animators who were alumni or soon-to-be employees of Disney, Warner Bros., Pixar, and Dreamworks. The film's shepherd and director, Richard Williams, took commercial, TV, and film work so his studio could continue production. Those money gigs won him two Annies, a BAFTA, an Emmy, and three Academy Awards. His latter two Oscars were for his work directing the animation on WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT. Him using all that money and acclaim to pipe funds into his passion project for three decades is evidence of a rare kind of dedication, the kind seen in dudes like Kubrick, Welles, or Malick.

More than that, the film is something of a lost masterpiece. In it's original form (or, at least, the closest thing we have to it, Williams' 1992 workprint), THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER contains some of the most dynamic, complicated, and carefully designed sequences in the history of the medium. With a radically bizarre, foreign look, a minimalist story, and a dollop of Warner Bros. style lunacy, the movie is one of those perfect things, the fulcrum between highbrow and lowbrow, a personal, vibrant project impractically created on a grand scale. It wants to do what's never been done before, but in a way that doesn't call attention to itself (even if it ends up doing so). More than that, as technically impressive as it is, it's consistently and riotously funny as all hell.

However, despite the amount of time Williams worked on the project and the strikingly original nature of the animation, a completion bond company and cheapo producer Fred Calvert ended up taking control of the film away from the director. Their version excised over 20 minutes from Williams' cut, added new songs and voice-overs, and and completely reworked the tone of the film. This is the only completed cut of the film, the only version that was ever commercially released, and has kept Williams' painstakingly designed original vision largely forgotten and presumed lost.

But the legend of the project, and what it could've been, lives on to this day. Somewhat serendipitously, The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences hosted a screening of Richard Williams' '92 workprint in Los Angeles in December, just as a documentary about the 30 year production of THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER, entitled PERSISTENCE OF VISION, is making rounds in theaters across the globe. Watching both of these within about a week of each other was an awesome, humbling experience, and inspired me to write this piece about the several versions of THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER, the documentary that revolves around it, and my own personal history with the various incarnations of the film.

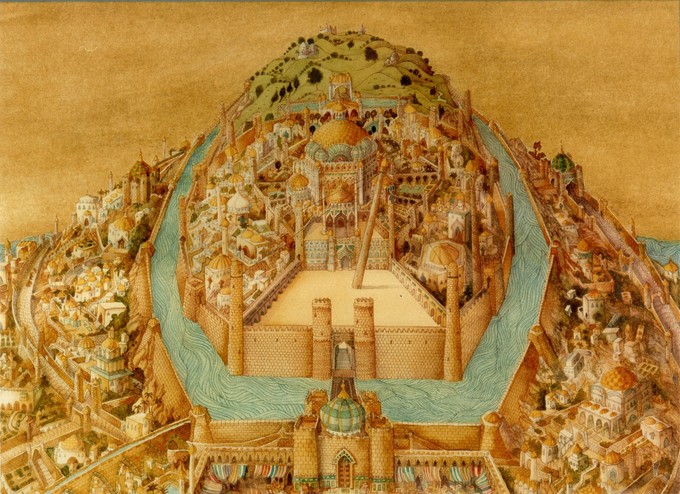

If you've never seen the film, THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER is about , well, a thief and a cobbler in an ancient Persian/Middle Eastern kingdom known as The Golden City. It is named such because of a superstition that the kingdom's safety will be maintained as long as three golden orbs remain atop the city's tallest spire. Through a series of misunderstandings and accidents, the cobbler, named Tack, and the unnamed Thief both find themselves in the presence of King Nod, his daughter Princess Yum-Yum, and the king's advisor, the shifty sorcerer Zig Zag. With the sacred golden balls within his grasp, The Thief cannot help himself and, with much difficulty, manages to steal all three orbs.

The king panics, foreseeing an impending invasion by the mythical and barbaric One-Eye army, and decides to seek the advice of a witch that resides in the nearby desert. He's a little long in the tooth (not to mention complacent and permanently sleepy), so he decides to send Yum-Yum to meet with her in his stead, but she demands that the wrongfully impassioned Tack accompany her. Little does Nod know that Zig Zag himself has stolen the golden balls away from The Thief, and is making a deal with King One-Eye to secure a high level of power for himself in exchange for the (metaphorical) keys to the kingdom. Tack, Yum-Yum, a group of well-meaning brigands the pair meet in the desert, and despite his best efforts, The Thief end up working together to ensure that Zig Zag's plan fails, the One-Eyes are defeated, and that the three golden balls go back to their rightful resting place high above the city.

When I first saw THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER, I was 9 years old. It had already reverted to its original title (although all other changes remained in effect), and was released on video with little fanfare (none of my childhood friends even knew that a movie called ARABIAN KNIGHT had ever existed). The version I saw as a kid was the theatrical Miramax cut of the film, clocking in at 72 minutes, and featuring the celebrity voices I mentioned above. It opens with a Matthew Broderick voice-over (as Tack) saying, "Legend has it that each shooting star is really is an Arabian knight riding across the heavens." He mentions that the story takes place "long before the tales of Aladdin and Ali Baba", and refers to the Golden City as Baghdad. A very clear context completely native to this cut of the film.

As a kid, you aren't even aware that such a thing as behind-the-scenes drama exists. You don't know that TOY STORY 2 was essentially made in half-a-year by desperately overworked animators. You don't care that in one version of A NEW HOPE, Han shoots first, and in another, Greedo does. You don't think that there may be director's cuts of ROBOCOP, ALIEN, ALIENS, or SUPERMAN II that may very well be superior to the theatrical versions. And at face value, without knowing a word of the story regarding the production of the film, I really liked THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER.

While I could do without the songs or the love story (much of which was added in later), I was enamored with the stylized look of the film, the reliance on physical humor, and the simplicity of the narrative. I remember getting in trouble for shouting the brigands' lines in my bedroom and laughing hysterically like a crazy person. But more than anything, I was in love with The Thief. As voiced by Jonathan Winters, I was gaga over The Thief's constant spew of sarcastic (and largely irrelevant) mutterings as his greed got him into (and out of) increasingly dangerous and large-scale situations. He reminded me of my favorite Warner Bros. character, Wile E. Coyote, reaching for the prize, getting beaten up for it, and going after it again undeterred. Years later, it would all click together for me: Ken Harris, a collaborator of Chuck Jones and the visual inspiration for Wile E. Coyote, worked with Richard Williams on THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER for years.

I was a fan of ALADDIN, and of course, The Genie, but in my house, my VHS copy of THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER got much more play. There was something about the movie that seemed very signature, charming, and un-Disney. As a kid brought up during the four-quadrant, Academy-friendly era of animation that included THE LITTLE MERMAID, BEAUTY AND THE BEAST, THE LION KING, and of course, ALADDIN, I found the more retro, dynamic style more to my liking than the CGI-enhanced, song-permeated trends of the time. But still, the movie was short, narratively similar to ALADDIN (particularly Zig Zag the vizier's plot to overthrow the king/sultan using his daughter's hand in marriage), and had a central love story that didn't jive with me at all. As I grew older, movies like FANTASIA, AKIRA, FRITZ THE CAT, and HEAVY METAL would be far closer to the forefront of my mind when it came to the subject of film animation. THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER was just one of the good ones, not one of the best ones.

Then, I read somewhere that the record for the longest production on a completed finished film belongs to THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER. It did not compute. That weird-looking throwaway from '95? Did that much work really go into it? More than I could imagine, as it turns out. The story of Richard Williams and his studio plugging away at the movie for decades before finally being shut down was irresistible to me. I'd always been a sucker for stories about artists willing to fight the tide and stick their neck out to advance the cinematic medium, like Welles, Chaplin, Coppola, etc., but I'd never heard this one. The biggest bummer? Because Wililams was never allowed to properly finish the film, there was no way of seeing what could've been before Fred Calvert and the bond company rushed the film to completion. I had positive memories of the cut I'd seen, but the knowledge that there was a different, longer, more expressive, and more personal version of THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER out there, one that I would perhaps never get a chance to see, stuck at my craw. That's when I came across THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER: THE RECOBBLED CUT.

In 2006, a USC film grad named Garrett Gilchrist took it upon himself to try and piece together what might've been, and set about editing a definitive cut of THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER. Using whatever materials he could get his hands on, including footage from the '92 Williams workprint and a Japanese widescreen DVD (all the U.S. THIEF AND THE COBBLER releases have been fullscreen), Gilchrist assembled what was, at that point, the closest thing to Richard Williams' original vision. More than that, due to the rise of Youtube (and the lack of any sort of real interest from parent company Miramax), THE RECOBBLED CUT was online, in high quality, available for any curious parties at no cost. Which, as a college freshman living in one of the most expensive cities in the country, suited me just fine.

Even with a healthy amount of the footage in rough or pencil-test form, it blew me away. It was like realizing, 10 years later, that there was a whole half of a movie after the intermission of LAWRENCE OF ARABIA, or that Adam isn't just sticking his pointer finger at the sky on the Sistine Chapel. I couldn't believe it. It seemed like the movie I'd known and loved as a kid, at least on the surface, but it was so different. There was barely any dialogue. The lead characters, whom I remembered as chatterboxes with the voices of Matthew Broderick and Jonathan Winters, were completely silent (save for a lone utterance by Tack at the conclusion, reportedly done by Sean Connery), as were formally verbose side characters like Zig Zag's pet bird Phido and his bloodthirsty pack of alligators (who he uses like sled dogs). The songs were out, and the love story between Tack and Yum-Yum was deemphasized as a result. There were blood splatters, sexual innuendos, and subtle asides that were as un-Disney (and unfit for mainstream family viewing) as something on Adult Swim.

More apparent than any of that was this ripe, cutting sense of madcap energy that I'd never associated with the film. Those Thief slapstick bits that I loved as a kid? Turned out they were actually far more brilliant in their original form. Just taking The Thief's voice away did wonders, making him into less of a sly troublemaker, and more of a pathetic, pathological character like my old pal Wile E. But it wasn't just that. What we got from Miramax in '95 was only a taste of the set-pieces, dynamite animation, and perfectly-conceived gags that Williams had cooked up over the years. There were these long, M.C. Escher-inspired designs and comedy bits that had been severely truncated for the theatrical release, but were easily the highlight of the film. Swooping camera movements, meticulously crafted backgrounds, and wonderfully expressive character moments that were inexplicably cut were there in full display, daring you not to stare in awe at the level of craft evident in every scene.

The crown jewel of the restored footage is the undoubtedly the full version of the infamous War Machine sequence. At the climax of the film, when King One-Eye and his army invade the Golden City, we see a massive mechanical structure, filled with a limitless abundance of gears, levers, and pulleys, which The Thief uses to steal back the precious golden balls as the machine breaks apart around him. In the ARABIAN KNIGHT cut, this scene is present, but it moves hella fast, is intercut with a (Calvert added) fight scene involving Tack and Zig Zag, and is peppered by one-liners, courtesy of the late Mr. Winters. Allowed to breathe on its own without the edits and voice-over, scene is, in my opinion, a mark of brilliance. In terms of technique alone, the amount of detail on the endless number of elements on display is remarkable. If contemporary CGI animators had designed the sequence I'd applaud them for their level of attention and their evident passion for the project. But for ink-and-color guys to slave over it for decades and then nailing it as perfectly as they did even in unfinished form, I must say that their virtuoso work is nothing short of legendary. Watching The Thief fly around, eyes affixed to his coveted golden balls, completely unaware that every situation he lands in presents a genuine threat to his life recalls my favorite Wile E. Coyote riffs, continually escalating into something that, if it were part of a symphony, would leave the conductor a sweaty, fevered mess. It made me fall in love with the Richard Williams who believed in this project so much that he essentially made it his life's work; my film-school brain thought, "This is what you try and do when you realize you have talent."

Still, there were flaws in the "Mark 2" version of the RECOBBLED CUT that I saw (Gilchrist's current, newly released version is "Mark 4"). While Gilchrist had the blessing and support of many animators who worked on the project, he, himself, only had so much access (particularly without the participation of Richard Williams), and was only able to get the film workable to a certain extent. As the project was compiled from a bunch of different sources, the quality of the animation varies from scene to scene, and, sometimes, from shot to shot. To smooth over some of the rough edges, Gilchrist used shots added later by Fred Calvert, as well as some original music and editing transitions. But it was a world's apart from the commercially available cut, and for providing all interested parties the only available look at what could've been, Gilchrist had earned his stripes in my book.

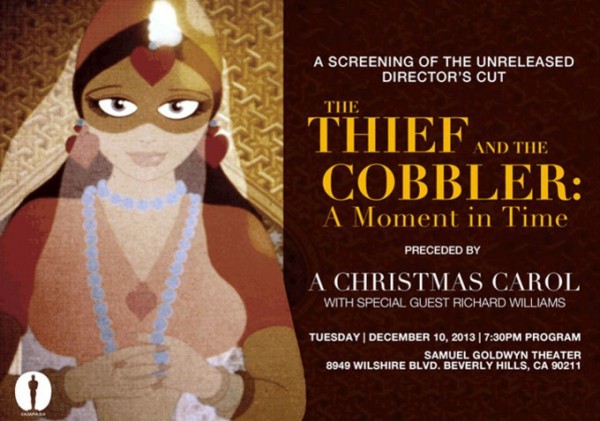

Cut to 7 years later. The above image gets mass emailed to those on the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences mailing list. The news trickles down the web to interested parties: the Academy was going to honor THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER by screening an "Unreleased Director's Cut" of the film. More than that, Richard Williams, who has taken a strict "no questions" stance regarding the film for the past 20 years, was going to be there. First thought: "It's terrific that they're going to pay homage to this unjustly forgotten work of art." Second thought: "Holy shit, I need tickets for this!"

Very little was officially announced about the screening, so my mind was abuzz with possibilities. Just what version of the film were they going to screen, the workprint, some interim version, or maybe even the RECOBBLED CUT? What would the quality level be? Was Wiliams going to do a Q & A? Would he address the differences between what we'd see that night and what Miramax had released in '95? And, perhaps most fascinatingly, was there a chance that this version could be the best one to date, the one that would be worth preserving for the ages?

What we saw at the Samuel Goldwyn Theater on December 10th, 2013 was dubbed A MOMENT IN TIME, and was Richard Williams' workprint that he'd created when he was still working on the project in 1992. Warner Bros., who began financing the formerly independent project in 1988, were very wary of Williams' ages-long production schedule, and once they saw that Disney was going into production on a distinctively similar project, ALADDIN, they sent TV animator Fred Calvert over to Williams' studio in London to check out his progress. What he saw, including Williams slaving over minute details while continually tossing whole scenes and characters out of the script, scared Warner to the point that they requested a work-in-progress cut of the film to screen to their execs. Wililams worked day and night to create enough storyboards, pencil-tests, and finished animation to have something concrete to show off his decades of work. Soon after he screened this rough cut, Warner shitcanned Williams, closed down his studio, and fired his staff, leaving the Completion Bond Company to try and finish the film as cheaply and quickly as possible.

Like THE RECOBBLED CUT, very few scenes roll by without the presence of unfinished animation, pencil-tests, storyboards, and even written direction dictating the proposed camera movements. But it felt like the thing. It felt personal, raw, the product of hungry artists working for decades to achieve something new and different. Scenes that were throwaways in the previous cuts, such as The Thief traversing a labyrinth of sewage piping and a dying soldier struggling to climb aboard his horse, became unabashed comic centerpieces. The witch character, rendered into a floating eye by Calvert and only in pencil-test form on the RECOBBLED CUT, was more fully-animated, becoming a memorable, interesting character in her own right. Nod's castle was bursting, more than ever, with gorgeous floor patterns, background designs, and architecture.

And that War Machine sequence. Oh man. Sitting there, watching the rapturous audience eat up Richard Williams intended vision for that climax, knowing that he was in the crowd watching them eat it up for the first time on the big screen, was a religious experience. There we were, at the Church of Williams, in deep reverence of the work he had bestowed up on us. As The Thief bounced back and forth as every element of the War Machine worked, in Rube Goldberg-esque fashion, I was in pure bliss. Not only because the quality and ambition of the animation were jaw-droppingly impressive, but because my feelings were reaffirmed by the entire theater. If you were watching the screen, you couldn't help but admit that this was something to be in awe of. As the credits rolled, the audience shot out of their seats in an appreciative standing ovation that rivaled any I'd ever been a part of. The tickets that night were only 5 bucks a pop; even if they'd been 50, we'd have gotten our money's worth.

Williams, at age 80, was all smiles and appreciation during the Q & A. His baby had been shown, and it had played wonderfully after decades of being treated as an example of dedication and passion run amok. He talked lovingly of the old animators who worked on the film, like Art Babbitt, Roy Naisbitt, and especially Ken Harris. Williams credited Harris with serving as his mentor on the project as well as the lead animator for the character of King Nod, and there was a clear sense of affectionate nostalgia in his voice as he recalled their days in his studio during the early stages of THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER's production. But one subject wasn't even broached: that miserable, heartbreaking period between 1992, when the workprint was struck, and the 1995 release of ARABIAN KNIGHT. No matter. It was a night of nostalgia, meant to honor the film and its creator, and no one was itching to sullen the mood by lingering over the grim realities of a corporation-dominated film industry. It was a miracle that Williams had finally agreed to talk about the film at all.

But you can't help being curious, right? I mean, this is 30 years of a man's life we're talking about here, not to mention the legendary and up-and-coming artists who worked at his studio during that time. As much as I appreciate separating the art from the artist, and the final result from the painful birth that spawned it, I'm from the DVD featurette generation, and as such, I want the juicy details. And wouldn't you know it, Kevin Schreck went and made a documentary giving us just that: a play-by-play of the conception of THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER, the 30-year process of animating the film, and the scuttlefuck of its collapse and eventual compromised release.

A PERSISTENCE OF VISION has everything you could possibly want in a THIEF AND THE COBBLER retrospective documentary. A clear timeline paints the picture clearly, top-to-bottom, without the pretentious flourish a studio-sanctioned doc may have tacked on. Animators, old and young (well, younger), who worked on the film contribute candid interviews about their time with Williams in London. Footage from all the cuts, Williams' other work, and even ALADDIN are used to illustrate the talking points. And most impressively, there's an abundance of archival footage taken at the actual Williams studio while work was being done on the movie, complete with extensive looks at Williams himself discussing his intention, overseeing his animators, and decrying both the financial and personal pressure on their progress.

One important aspect Schreck emphasizes (and discussed in our interview) was the level of influence the project had, not just on ALADDIN, but on a bunch of different projects. The film was being developed for 10 times the length of any normal studio picture (including most animation), and Williams, to keep his funding and a healthy reputation, would show off his progress to anyone within earshot. Many times, he'd let animators and distinguished visitors take home discarded cels and storyboards as souvenirs. In an industry where "everybody steals from everybody," Dick Williams was an easy mark.

To illustrate: remember how AVATAR was in development for almost a decade, but we didn't really see a frame of it until 5 months before its release? Well, imagine that a year before AVATAR, some former WETA animator directs a flick about blue humanoid aliens, and an invading human force that threatens to oust them from their land. Go even deeper: former mentor becomes the villain, the local religion wins the human lead over, etc. One could easily surmise that he may have picked up some elements from the in-house work on AVATAR, right? But his film comes out first, and James Cameron's film that was gestating for ten years gets brushed off as a ripoff. That's essentially what happened to Williams. Except he was working on his film for almost 30 years when ALADDIN came out. Now his baby's an ALADDIN clone. I can't even imagine the existential agony he went through watching a squat, white-turbaned sultan get conned by his duplicitous, long-faced grand vizier (Zig Zag's blue skin was transplanted over to the Genie) in one of the biggest (and most acclaimed) films of the year. I get pissed when someone makes a penis joke I thought of first. This was his life's work.

The story of PERSISTENCE OF VISION, and of THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER, is a painful, harsh one about the realities of moviemaking, but I can't help feel that the ending of the story is shaping up into a happy one. No less than the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences saw fit to publicly screen the film (in its original format), and honor Richard Williams in the process. Schreck's PERSISTENCE OF VISION, while featuring a ton of licensed footage that make it virtually impossible to distribute commercially, continues to tour around the world almost a year and a half after its first festival premiere. The recently-released RECOBBLED CUT MARK 4 features the most high-quality and painstakingly restored elements of the film of any publicly available version of the film, to date.

More than anything, Richard Williams lived to see his life's work appreciated. Sure, he'd been honored with a bevy of awards for his efforts over the years, but those were all side jobs to fund his passion project, which was THIEF AND THE COBBLER. That was the movie he'd plugged away at for decades on end (have you ever spent more than a couple of years on anything, save for a marriage?), and the one that represented all he'd learned and all he wanted to pass on in the realm of animation. He's been teaching and lecturing for a long time now, and his book (The Animator's Survival Kit) remains a must-read for burgeoning animators. But THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER shows a technique, an ambition, and a deep sense of joy that could never be taught.

Because in the end, to paraphrase Morpheus, no one can be told what THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER is. You have to see it for yourself.

PERISISTENCE OF VISION is screening at the Bloor Hot Docs Cinema in Toronto every day this week through Thursday (1/16), save for Tuesday (buy tickets here). For updates on further screenings, or simply for more info on PERSISTENCE OF VISION, check out the film's Facebook page.

Check out my interview with PERSISTENCE OF VISION director Kevin Schreck.

-Vincent Zahedi

”Papa Vinyard”

vincentzahedi@gmail.com

Follow Me On Twitter