When the unthinkable occurred on September 11, 2001, there were three immediate questions: "Who did this?", "Where do we fight them?" and "How do we make sure this never happens again?" Though there hasn't been a major terrorist attack by al-Qaeda on American soil since that day, it is very difficult to argue that the U.S. government's answers to these three questions were satisfactory. By needlessly dragging Iraq into the fray, the U.S. sacrificed over 4,000 soldiers, while over 100,000 Iraqi civilians were killed. By torturing detainees in order to gain information on future attacks and/or the whereabouts of high ranking members of al-Qaeda, the country forever ceded the high ground on the issue of human rights. And by stepping up the drone program to keep as many U.S. soldiers out of harm's way as possible, the Obama administration has looked the other way as countless innocent civilians have been mistakenly killed in supposed "surgical strikes".

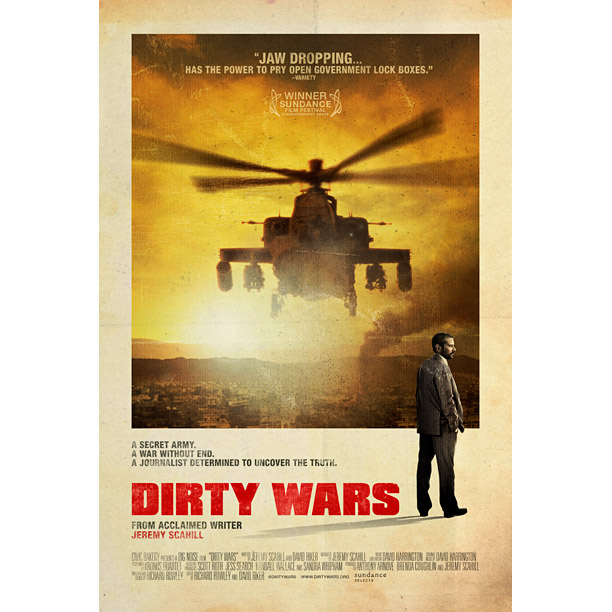

As the fog of perpetual war has grown thicker over the last twelve years, journalist Jeremy Scahill has relentlessly investigated America's waging of shadow wars. He's traveled to various war zones, documenting the actions of the private security outfit Blackwater in his 2007 book BLACKWATER: THE RISE OF THE WORLD'S MOST POWERFUL MERCENARY ARMY, and, most recently, shedding light on the clandestine assassination of high-value targets by the Join Special Operations Command in the book and documentary DIRTY WARS (opening in limited release June 7th). Whereas the book is an exhaustive account of JSOC's activities and the many tragic mistakes they've made along the way, the film focuses in on Scahill's investigation of a joint U.S.-Afghan police raid in Gardez, Afghanistan that left five dead, including two pregnant women. From there, Scahill builds his case against the Obama administration's blundered foreign policy, highlighting its support of ruthless Somali warlords and the drone strike that killed Abdulrahman Anwar al-Awlaki, the U.S.-born son of suspected terrorist Anwar al-Awlaki (who had been assassinated two weeks earlier).

Director Richard Rowley has delivered in DIRTY WARS a stylishly persuasive procedural that capitalizes on Scahill's probing intellect and world-weary prose style. It's a sobering examination of a distressingly under-reported story - which got a bump in coverage two weeks ago when Obama announced the "end" of the War on Terror (only to quickly take a backseat to the murder trial of Jodi Arias). I spoke with Scahill prior to Obama's speech, but these issues are still incredibly pertinent. Until this administration is aboveboard about the extent of the drone program (and the civilian casualties incurred), Scahill's questioning remains vital.

After marveling at the fact that we're both named Jeremy and were born on October 18th (I've got a year on him, but he's probably been shot at more than me), Scahill and I fell into into a wide-ranging conversation about the film, the possibility of an end to our perpetual state of war, and the bipartisan nature of this enduring conflict.

Jeremy Scahill: (Looking at my iPhone) The quality is actually really good on these things.

Mr. Beaks: Even when you're out in a war zone?

Scahill: But I'm a print reporter normally. Most of what I do in life, I do exactly what you're doing here. I use my iPhone, I put it down on the table. It's much better when you don't have cameras around you. People are more themselves. It's a big challenge. I hated having a camera following me.

Beaks: That actually leads into my first question. Had you interviewed the families prior to putting them on camera?

Scahill: No. I don't think in any case had I already done an interview. Not in Gardez, not with the Awlakis, certainly not with the Somali warlords. This was a challenge in the film. If I'm doing what you're doing, where I'm just a print reporter, you can kind of ease your way in with someone, you can be talking with them and then say, "I'm going to ask you that on the record," and you put your recorder out. And sometimes people forget the recorder's there. To get people to agree to talk to you as a reporter sometimes is tough enough. To get them to agree to talk to you as a reporter and allow it to be filmed is very difficult. And then the third thing is to not have them play for the camera, which is a challenge. I'm trying to answer your question literally and honestly. I believe that the first time you ask someone a question, that's usually their best answer and is most sincere. But when there's a camera on them, there's a tendency to want to act for the camera, and we wanted to get away from that. So what we did in the case of Gardez is we sent an emissary down to talk to that family and explain what we wanted to do so they wouldn't be caught off-guard. They really were not used to being on camera at all, and remarkably just ignored it. They did not seem to be putting on any kind of a show ever. We had other stories we were pursuing where the people just seemed to want to talk to the camera, and we didn't want that.

The other thing we did is that we often would have the local folks with us who spoke the language fluently, and we would tell them the arc of what we wanted to talk about, the ground we wanted to cover. And instead of interrupting the people we were talking to every thirty or sixty seconds to have it translated, we wanted people to tell full stories. Sometimes people would talk uninterrupted for ten or twelve minutes without me stopping them at all. Then I'd catch up with the translator and say, "Did you cover this?" And then I'd say, "Okay, I want to talk about this thing. What we found is that when people started to get into a story in their own language, they hit a real path of sincerity. Once they got beyond thinking "How do I need to carefully position this statement," then they're off. In filming with these families, we always tried to find moments where they were truly telling a story, reacting to something that was said, or relaying information in a real, sincere way.

Beaks: What I found surprising right from the beginning is that the film is quite stylized. It's not that it feels staged, but it does feel polished, which is rare and sometimes risky for documentaries.

Scahill: I understand the point you're making. First of all, when we started filming it, we had a bit of a different concept about it. It's not that I wasn't going to be in the film, I just wasn't going to be in the film in the way that I am. It wasn't going to be a personalized narrative story. I was going to serve as a kind of tour guide. We'd go from here to there and explain some of the history of the whole thing. It wasn't until we'd already been shooting that we decided to shift gears on it.

On the issue of being stylized and polished, I will say that if you look at Richard Rowley's work that he's done for Al Jazeera or other stuff as journalism, he has a distinct style. He is a really talented guy, and he's got a very good eye. I look at it, too, and I feel like, "Wow, I can't believe this is our film!" Part of it might also just be that Rick was filming every single minute of my life; I felt like THE TRUMAN SHOW in Afghanistan and Yemen. I would yell at him sometimes and say, "Stop filming me!" I'm in a car, and I'm trying to take notes for the next place that we're going, and Rick is filming me. "We're driving by the most beautiful mountain range in the world, and you have your fucking camera on me!" There were things we had to do once we realized we were making a film that was more personal. I'm an old school journalist, and I use paper and photos and stuff like that, and I was already ahead of the filming on my own stuff, so we had to dismantle this wall that I'd built, and then Rick filmed me putting my wall back together. But I had already been doing all of that stuff. Outside of that, I don't think there was anything that we had to go back and shoot for continuity. It was all stuff that Rick had shot in the field.

Beaks: In terms of documentaries like this, there's a flurry of fact checking that occurs after the release. You worked for Michael Moore, and he's been hammered more than anyone in this regard.

Scahill: I worked for him on THE AWFUL TRUTH as a junior producer. It wasn't like I was the producer of THE BIG ONE or BOWLING FOR COLUMBINE.

Beaks: But when you're making a documentary, and you're condensing things for the runtime, and perhaps having to leave out things that would provide greater context, how do you as a journalist contend with that?

Scahill: I wrote a book that's almost 700 pages long that just came out, and I tried to tell the complete story in the book, particularly in the case of Anwar al-Awlaki and all of his complexity. I think what we tried to do in telling multiple complicated stories is present as much of the story as we could without creating a situation where people are going to tune out and not pay attention to it. We really didn't want to have statistics or use cards with words on them, anything that would make it feel like people were in a classroom. We wanted to try to tell the story that captured part of the essence of what's happened in our country and around the world since 9/11. But if we wanted to tell the complete story of any of the individuals in our film, the movie would be fifteen hours long. I believe totally in the integrity of the film, and inevitably whenever you're telling any one story - and this is true in print journalism, too - there are things that get left out that someone could say, "Oh, you didn't put this in!" We're not so full of hubris that we're not open to self-criticism or legitimate criticism, but I think what we made is a film that is an honest portrayal of what's happened with these wars since 9/11.

Beaks: The coverage of the drone program has been fascinating, particularly in the way people on the left have reacted to it. I keep thinking of the scene in DIRTY HARRY where Clint Eastwood, having shot the Scorpio Killer in the leg, proceeds to step on the wound to get information out of him that might save lives. As he does this, the director pulls way back via a helicopter shot until they're specks in the distance on this football field. Shane Black has said that this is the moment where we acknowledge there are people out there doing ruthless things to keep us safe from monsters, and we'd rather not know their methods.

Scahill: And someone says that in our film. We'd don't want to go behind the curtain and see what goes on.

Beaks: And there seems to be a comfort level with many Americans, who say, "I don't want to know about it, but if it gets results, then fine." Do you think this is at play with regards to Americans' interest in the drone program?

Scahill: I think with liberals, part of it is that people just trust Obama, and if Obama says this is what we need to do to keep Americans safe, and we do everything we can not to kill civilians, and this is a surgical program, and sometimes innocent people die, but mostly we're just killing terrorists... I think a lot of liberals are willing to just trust him on that. I've certainly seen a different reality of that on the ground. I actually think we're making more enemies than we are killing terrorists, which is a pretty sobering thing to say. Another part of it is that it's easier to outsource it to someone else. "Oh, the people in the White House are making that decision. I don't want to confront any of that." People in this country are so tired of war, and right now the only people who are required in any way to pay attention to it are people who have loved ones deployed. For the most part, most Americans don't spend much time thinking about the drone program at all. And it's a tough ask anyway. To ask someone who's working two jobs and is trying to raise kids in an economy that's up and down, "Oh, why don't you care about what happened in this Yemeni village of al-Majalah in 2009?" It's a tough ask. But I do think if there was a Republican in office doing these same things that you would not see polls indicating that seventy percent of self-identified liberals support the drone program. To me, people should ask themselves why. Because the next time a Republican is in office, they're not going to just continue this stuff, they're going to want to expand it. And we're going to look back and say, "Wow, I was supporting it when it was Obama, but now that Jeb Bush is doing it..." or whoever the next Republican president would be... it's interesting.

Beaks: They're not going to have a leg to stand on. The same thing happened to every Democratic congressperson who voted for the war in Iraq.

Scahill: How do you walk back from that? There are a number of reasons Obama emerged as the candidate in '08, but he was really able to hit away at Hillary Clinton and Biden because they voted for the war. And on the foreign policy thing, it was what set him apart from the other viable Democratic candidates: he wasn't in office, so he couldn't have voted for it. But he had also given a speech in October of 2002, before he was a senator, calling it a "dumb war". That's speech is interesting. He doesn't say he's against all wars, he says he's against "dumb wars". You could tell he was already carving out a position so that he was going to be able to say, "I can wage a smarter war." That's what he did in '08 campaign against McCain. He said, "I'm going to wage a smarter war, I'm going to take the fight to the terrorists, and I'm not going to get us bogged down in Iraq." And that's what he says today with liberals. "I'm not going to deploy large numbers of troops, I'm going to use the drone program." Although he doesn't often talk about the drone program. He just talks about how we're killing the terrorists.

Beaks: That's one of the frustrating things about watching your documentary, the realization that we're mired in this again. We seem to specialize in mires.

Scahill: (Laughs) Yeah, we are good at it.

Beaks: What is the way out? You've spent so much time covering this. Do you see any conceivable way to extricate ourselves?

Scahill: Look, I'm not naive about the threats that face our country. I've met people who would love nothing more than to blow up a U.S. airplane, and when I talk to people who support actions like that, I try to understand where they're coming from. "Why would you want to do that?" Just as a human being, I can't ever imagine dreaming of blowing up someone's civilian airliner. But I know that those people exist, and that they are plotting, and that if they had a chance to blow up a subway in our country, they would do it. Or set off a bomb in a shopping mall. We don't know the exact motives for the Boston Marathon bombing yet, but I think that we will see other attacks in our country, so we have to have something to confront people that want to do that.

I think we made a big mistake by using words of war to describe the fight against terrorism. I think we have a robust justice system, and I would like to see us as a society demilitarize our approach to not just terrorism, but the war on drugs. We're operating out of fear. I would like to see an effort to bring terrorists to justice, and not have justice defined as rounding up the posse with pitchforks. To me, it's not about who someone like Anwar al-Awlaki is. Awlaki may be guilty of every single thing he's been accused of in leaks - not in court, because he was never charged of a crime. He might be the awful, vicious terrorist that people say who he is. I found things that he said deeply offensive and reprehensible, some of them are potentially criminal. But I believe in the rule of law. And for me, it's not about "Who is Anwar al-Awlaki?", it's "Who are we as a society?"

You ask me what can be done about it? On the drone thing, not to sound like I'm a politician because I don't like politicians, but I think it's hit a point where there should be a moratorium on drone strikes. Remember when Governor George Ryan in Illinois called for moratorium on the death penalty? It wasn't because he was an Amnesty International activist, it was because of DNA evidence exonerating death row prisoners and realizing we're putting people to death who are innocent. If we don't know the names of the people we're killing in drone strikes, but they're the target because of a pattern of life, and we don't have actual evidence against them? It's like pre-crime. It's like MINORITY REPORT. I think there could be a moratorium on it, and have an actual investigation like, "Who have we actually killed? Have we killed more terrorists than we have made new enemies?" And if we determine that we're actually fueling the very threat that we claim to be fighting, then we have to have a reset button hit, and say, "What would an actual national security policy look like?" I'm not a pacifist, but I've yet to be presented with evidence that suggests by killing that guy in a drone strike we have stopped an imminent plot against our country. I haven't seen evidence to suggest that's happened. That would be a different case, but that's always what the Republicans said: "We have to torture these people to prevent the next terror plot." It turns out that was a lot of propaganda, and that torture didn't lead to much of anything. I think we're doing that with the drones, too. I think we should do something about guns in our country. Look at the threat being posed by these wackos with guns.

Beaks: Well, we've just become so comfortable with guns in our country. I grew up in Ohio, so there were hunters--

Scahill: We're not talking about hunters.

Beaks: Yeah, but they are so aggressively targeted by the NRA to see every piece of gun control legislation as "They're coming for your rifle. They're coming for it all."

Scahill: I'm from Wisconsin, and, I mean, my parents didn't have anything to do with guns. They were nurses, and they saw the effects of gun violence in the city of Milwaukee. But go up north, and they're hunting, and everybody loves their guns and their camouflage. The issue isn't about just guns in general. We have this reality where we've had these school shootings where kids have been killed. There was Virginia Tech and Newtown, and our response to that compared to our response to terrorism is very, very different. The fact that we are so terrified of guys in the mountains of Yemen, and are willing to spend billions of dollars to try to hunt them down and kill them, and we can't figure out a way to have any effective legislation on guns in this country... I'm sorry, but if a terrorist had gone in and shot up Newtown, could you imagine what the reaction would be in this country? Why aren't we doing something about the people who are doing this? Our priorities are so out of whack.

Beaks: Your reporting over the years has been very illuminating, but I'm exposed to it because I tend to watch news and read websites that reflect my sensibilities. How do you go about reaching the people who don't generally land on your end of the political spectrum? I ask this because of lot of your reporting is tough on the left, and strikes me as common sense much of the time. The drone program is something that should bother Democrats and Republicans.

Scahill: When I heard that Rand Paul was going to do this filibuster about the Brennan nomination, I was like, "This is going to be great." (Laughs) I think I made a big mistake in assuming that it was going to be great, but it was like, "Someone is going to do this."

Beaks: Some folks got a little carried away on Twitter.

Scahill: I never did the "Stand with Rand" thing. I won't stand with anyone who takes the reprehensible positions that he's taken on race and women's rights and other things. But I give Rand Paul credit for raising this issue in a way when Democrats were either silent or cheerleading it. There were life-or-death issues he was raising there. I think you do have this weird moment where some Republicans, for their own politically opportunistic reasons, are criticizing the drone program, but I don't believe for a minute that there is grand sincerity on their part. "Obama loves drones, we must hate drones." That's not principle. But I do think that there is a shifting reality about this. I think that a lot of conservatives are getting sick of this, and maybe some of it is because they don't like Obama. But maybe some of it is they don't want a perpetual state of war either given our economic situation. Just the sheer money being spent on these wars is incredible. I've met a lot of people from the military community and Special Ops community that I never thought I would be friends with. I've developed friendships with them over the years, and we have great debates and arguments. Just as I want people to see a kid in Yemen who lost their parents in a drone strike, or a woman who had several of her children killed in a cruise missile strike, I also think it's important for those of us that are more on the liberal or left side of things to realize the humanity of the people we think we're arguing against. I talk about this in the book, but I've learned a hell of a lot from knowing guys that are Navy SEALS or in the Special Ops community. They've changed my view on some of this. I don't have a cartoonish version of them anymore. I think ten years ago, I had a very cartoonish version of who those guys were.

Beaks: And yet there seems to be a split in that community. You've got the guys who are in the service for life, and then you've got the guys who "go Blackwater".

Scahill: That was the slang of it, and that's how I met those guys. I would get emails or Google chats or guys would come up to me at events and say, "I really don't like your politics at all, but you were right about those Blackwater guys." I would always tried to reach out after that and say, "Would you like to get a beer?" I was stunned that these people were even talking to me because I just thought they all hated me. But then it became a thing of "They're really interesting." They're not a homogenous bunch. There's great diversity in that community. One of the funniest things is that General Stanley McChrystal is apparently a social liberal. I think that's true of some of the folks in higher positions in the command of these things, that they have MSNBC on, not Fox News, and yet they're implementing the military policies that Fox News is cheerleading. But they'll say, "Oh, yeah, but we support gay marriage."

Beaks: I want to bring up General William H. McRaven, who has been able to operate in the shadows for so many years. It seems that one of the major thrusts of your book and film is to put a face and, I guess, a name to this hugely important figure in our military.

Scahill: I do think he's one of the most powerful figures in modern American military history. You were asking about what you put in and what you leave out: a film about McRaven would be fascinating. He wanted to be James Bond when he was growing up, and he was an original member of SEAL Team Six, but he didn't deploy early on after 9/11 because he hurt his back in a parachuting accident, so he ends up getting brought in to advise the National Security Council right after 9/11 in developing a High Value Targeting program. He sees first-hand how the White House works. Then, as he recovers, he's one of the people who leads the hunt for Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Most of his life, though, he spent working on covert ops or helping to develop the targeted killing program that he would then lead under President Obama. Is the whole story of McRaven told in our film? No. We sort of meet McRaven when he's already entrenched in it. We talked about how to do that. I really wanted to tell a more complete story of McRaven. I also wanted to tell a more complete story of Awlaki in the film, because I think Awlaki is really fascinating. But I think also there's been a lot of media coverage of some of these issues, and we were trying to tell it in a way that was true to the facts, but also gave people a sense of it being a part of a broader narrative, and not getting bogged down in any one person's story at any moment.

But I don't see McRaven as the face of this anymore than I see Obama as the face of this. There was a Slate article someone sent me about our film where they were calling it an "anti-Obama film". I don't think Obama would see it that way. I don't think it's a full-frontal assault. Obama appears in the film twice: once is very early on when he is giving these speeches talking about "We're going to end our use of the state secrets privilege", and the other one is when he kills Osama bin Laden. To me, part of what is really remarkable is that it doesn't have one particular face. It's not Bush-Cheney, which is what a lot of liberals thought it was, and it's not Obama. It's going to be all of these people. It's a bipartisan project that's gone on for a very long time, and it is going to endure because it is a bipartisan project. McRaven and Obama are peripheral figures in the film, even though the mystery of McRaven... I remember the first time I saw that McRaven picture, and I was feverishly Googling who he is. It's very interesting. There was very little written about McRaven prior to this.

Beaks: So are we still stuck in this Military Industrial Complex syndrome? At base, are they the ones championing and profiting from this perpetual war?

Scahill: A few years ago, I may have gone on a rant about this when you asked me that, and talked about the Military Industrial Complex and the no-bid contracts of the Bush-Cheney era. I think our campaign finance system is rotten to the core, and I think corporations are in total control of both parties. Not in a sense that they're fat white guys smoking cigars in a back room saying, "Pass this legislation, don't pass this legislation!" The whole structure of our electoral process, the idea that members of congress spend a majority of their time fund raising for their next campaign, and that their campaign contributors from huge corporations can dictate how they're going to vote on issues is responsible for so many of our problems. The Military Industrial Complex will give more money to Democrats if they think they're going to win, and more money to Republicans if they think they're going to win, and that says a lot about who's in control of our politics.

Beaks: Having gone through this experience, do you see a value in making a complementary film every time you write a book?

Scahill: I wasn't even sure that I was going to write this book. I don't remember exactly when it was that I committed to writing the book, but it was in question for a bit of whether the two were going to be entirely related. The film and the book are definitely different creatures, and part of what the film turned into was the filming of an investigation that became a book. But we don't have a moment at the end of the film where I'm speaking at a bookstore somewhere. (Laughs)

But I love film, and films really resonate with me. I think we wanted to try to make a film that would stand on its own legs as a movie and not feel like people are in a classroom. We wanted it to be accessible. I'm from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and I want it to be accessible to people from rural Wisconsin who maybe aren't paying attention to these issues. I want them to be able to walk into the theater, and feel like they came away understanding something about how our country has changed over the past twelve or so years, but also to feel like they watched a movie and weren't just inundated with information. To me, those are the best movies, when you can just get lost in it for an hour-and-a-half. It's totally different from the film we made, but when you watch Werner Herzog's films, he really gets you into a trance. You enter his mind, and he takes you on an adventure. To me, that's really an accomplishment in a film, when people feel like they're on the journey with you. I didn't want it to feel preachy or like I'm trying to "learn you all on the facts". I wanted to say to people that the narrator is fallible, too, and we're going to take you on a trip. I don't know if we ended up achieving that, but that's why we chose to tell it that way.

DIRTY WARS opens in limited release in New York City, Los Angeles and Washington D.C. on June 7th. It will expand throughout the month. It is highly recommended.

Faithfully submitted,

Mr. Beaks