Leos Carax's HOLY MOTORS is the film of 2012, and beyond that I'm not sure what to say. I've seen the movie twice, and both times I've walked out exhilarated, yearning to make sense of it all and happily flailing. Clearly, Carax is commenting on the state of the cinema, and, near as I can tell, arriving at contradictory conclusions about its well-being. Such ambivalence is expected: the one-time wunderkind of French cinema has been battling for over a decade to make his fifth feature, and is still atoning for the sin of spending three years and a great deal of money to realize his 1991 masterpiece, THE LOVERS ON THE BRIDGE. When financiers hold your masterpiece against you, your future as a filmmaker must feel forever in doubt.

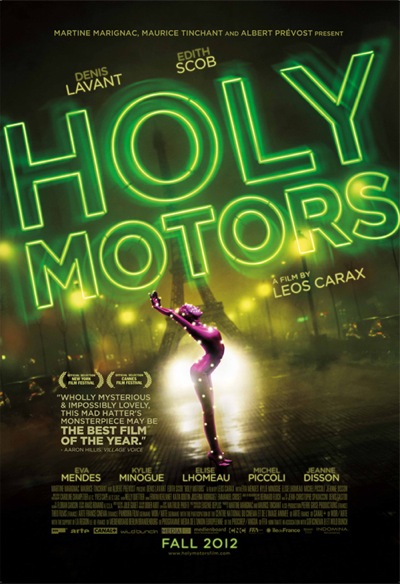

And so it seems that Carax has thrown everything into HOLY MOTORS as if it might be his last movie. It's a disorienting day trip with M. Oscar (Denis Lavant), a seemingly wealthy man who undergoes multiple transformations in the back of his limousine, repeatedly emerging as radically different characters with objectives ranging from the mundane to the murderous to the utterly inexplicable. Lavant's performance is a shapeshifting triumph worthy of Lon Chaney, whose makeup wizardry is homaged as the chain-smoking Oscar carefully applies a variety of old-school wigs, latex and appliances. Everything Oscar does appears to be a put-on of sorts; they're a series of brilliant, but sadly disposable illusions performed for no one in particular. It's a giddy, unexpected thing - as if Carax set out to eulogize cinema, only to discover it's as vibrant and vital as ever.

If you've never seen a Carax film before, HOLY MOTORS is an ideal introduction; it's playful, generally good-natured and filled with ecstatic moments. You may find yourself wondering "What the fuck?" on several occasions, but when that question is prompted by an impromptu accordion rendition of RL Burnside's "Let My Baby Ride", honestly, who the fuck cares? Roll with it, and enjoy not knowing what's going to happen next.

I had the opportunity to interview Carax during the AFI Film Festival earlier this month, and found him to be as unpredictable as his films. I knew from seeing him at a Q&A years ago that he'd have no interest in discussing the themes of HOLY MOTORS, so I tried to delve into his process, and how he views his career after the tumult of THE LOVERS ON THE BRIDGE and the frustration of the last twelve years. He didn't hold back.

Mr. Beaks: Have you had a chance to see any movies at the fest?

Leos Carax: No. I don't see many films anymore.

Beaks: Is that by choice, or do you just not have the time?

Carax: I saw lots of films when I discovered cinema. I discovered cinema at the same time I started to make films, so from age sixteen to twenty-five I saw lots of films. And then when I started making my second feature, I decided it was time to start making my own films. It's different when you start very young and you discover cinema at the same time. Your films are going to show that love for cinema, which is nice. It's fine. But it cannot become the subject of the film. So after two films, I felt that I had paid my debt of love for cinema, and that I could try to invent my own way.

Beaks: You made your first feature [BOY MEETS GIRL] at twenty-three, and it is very much a dialogue with cinema. Had you to do it all over again, would you have preferred to give yourself a little more time to study and digest film before making your first feature?

Carax: When you start that young, it's like a bluff. You have to bluff people to make films. I had never been on a shoot before I made my own films. I had never studied film. So I had to pretend to people that I knew how to make a film, when, in fact, I didn't know at all. But discovering cinema was such a relief. Although I went to the cinema as a kid, I didn't fully understand there was a man behind the film. When I understood that, it was a relief that there was a place, an island of cinema, from where you could see things; you could see things like life and death from a different angle. That's the place I wanted to live, on this island. I think in terms of career, what age should I have started or studied? I just wanted to get there.

Beaks: In just a very basic sense, how do you construct a story? How do you decide that an idea is worth filming?

Carax: I'm not a storyteller. Sometimes I wish I was, but I'm not Hitchcock. My films don't come from ideas; they usually come from one or two images or one or two feelings. I try to edit these feelings and images together, but I'm never sure it's even going to make something people call a movie. Many times people have said my films are not films. It's just that at one moment, you need to do something. The need is the thing. And sometimes you need to do something that you can't do. I guess if you're a storyteller, you feel if you have a good story, you make a film. I don't work that way. I'm not looking for a good story.

Beaks: (Laughs) What do your screenplays look like? Do they look anything like traditional screenplays?

Carax: Yes. (Laughs) I'm not sure what a traditional screenplay looks like, but I think they look that way. I'm not a writer, so once I think I have something, I have to put it down to get the money and for the crew to read. It's never very far from what the film becomes. I keep rewriting and making changes, but it's not completely different from what's on paper.

Beaks: In several of your films, you have these ecstatic moments that seem to come out of nowhere. In MAUVAIS SANG, it's the "Modern Love" sequence. In THE LOVERS ON THE BRIDGE, it's the Bastille Day celebration. In HOLY MOTORS, you have the accordion entr'acte. How do these moments come about?

Carax: They are feelings. There's a need for joy in film. It can also be pragmatic. Sometimes my films were very hard to make. THE LOVERS ON THE BRIDGE was very hard to make for the actor [Lavant] and the actress [Juliette Binoche], because they were playing homeless people and because it took three years to make. I don't direct actors really. I choose them, and then it's all very physical. You say, "I want you to walk like that," or "I want you to talk like that." It's not much about psychology. So in this process... there's got to be a space for something purely joyful that you have to prepare for or work for. You might have to learn to dance or do acrobatics or to play an accordion or to parachute from a plane. There's got to be physical stuff that you rehearse and prepare for. You want life to get into a film. You don't want a film to be dead. And all of these things help us survive. That's why there's often music in these moments. I think music and cinema share this sense of joy. It's very organic. And the ambition would be to one day to make a film that would be music. Not a musical, but a film that would be music. That would be my biggest ambition. But I am not ready.

Beaks: A film that would be music: can you articulate what that would be?

Carax: I don't know what it would be. Maybe HOLY MOTORS is the closest. But what I mean is that a composer has to hear what he composes. He has to hear it. It's not about writing a story; it's about hearing something and transposing it. This film... because it was made so fast and imagined so fast, it was made out of the rage of not being able to make other films. It happened to me like that. I can't say I heard it and wrote it down, but it happened a bit like that.

Beaks: It's interesting that you say this was made in a rage. It's been so long since POLA X, I couldn't help but feel that with HOLY MOTORS, as you cycle through all of these genres in a sort of celebration of cinema, you were saying, "If I never get to make another movie, this is everything I love."

Carax: Maybe I was. I didn't think that way. I think in terms of cinema and genre, etc... I didn't think much. (Laughs) I think I tried to invent a science-fiction world not very different from our world where in one day, from morning to night, I could show what I feel is the experience of being alive. I could show all my feelings towards life and death, of meeting, losing, dying, falling in love, etc. Then, of course, because of the idea that this character would travel from life to life, I had to invent all of these lives. Now I can see how this is a celebration of cinema, that he moves from one genre to another. I know that. But I've shown the film to children, who are twelve years old, and they get it. You don't have to know anything about cinema, you don't have to know anything about my films, you don't have to know me to see the film.

Beaks: And yet it's so apparent that the Merde sequence with the GODZILLA music is a kind of monster movie.

Carax: But I've never even seen GODZILLA. It's just that when they asked me to make a film in Tokyo a few years ago [for the anthology film TOKYO!], I thought the music was perfect for this character, Mr. Shit. I'm not a cinephile. I did see a lot of films - silent films, Russian films, Hollywood films, New Wave films - when I was starting. But I don't see myself as a cinephile.

Beaks: But you were a critic early on.

Carax: Six months.

Beaks: So that's overstated?

Carax: Yes.

Beaks: Okay. Because it does get mentioned in your biography. How did the "Who Were We" sequence come about? What feeling were you responding to?

Carax: That came late to the film. First, I imagined a scene between Denis and Juliette Binoche, because they had been in two of my films together twenty years ago. Then I thought it was not a good idea because it would make the film nostalgic or something. I wanted to shoot a ghost-like scene in this old department store that's closed and demolished on the Seine in Paris. And I thought, "Who could the woman be? They haven't met in twenty years." Then the filmmaker Claire Denis mentioned Kylie Minogue. I knew the name, but I didn't know who she was. And I thought it would be interesting if she could sing. They have a past together, and the past is so painful that she has to go into a song. So I wrote this song, and I asked Neil Hannon to write the music.

Beaks: This is the first feature you've shot digitally. How did that go for you, and do you see yourself shooting on film again?

Carax: It's a long story. You know, when I was twenty I started making films with Jean-Yves Escoffier. He was a French DP, and he became my best friend. We were like brothers, and for ten years we saw each other every day. We made three films together. Then after THE LOVERS ON THE BRIDGE, we fought and didn't talk to each other for ten years. Then he moved to Hollywood and he died. After that, working on film, celluloid... it's so much work and so wonderful, but I feel that that made it easier to go from film to digital. I didn't have Jean-Yves. But working on digital... I don't watch dailies anymore. That changes everything. I used to remake everything. So if you don't watch what you're doing, it gives you another strength - although I hate digital because it's not ready. It's been imposed on us like a medicine for a sickness that doesn't exist. I do try to use it to invent. That's why I put in this motion capture scene. I'm not nostalgic about celluloid; cinema has had to reinvent itself every twenty or thirty years, and I try to do that. The primitive power of cinema is being lost every year. No one is afraid of a train coming into the station anymore, so you have to reinvent it. That's the job of every filmmaker: to reinvent the primitive power, the holy power, of cinema.

Beaks: Do you feel that 3D or IMAX are good tools for that?

Carax: Filmmakers are tools for that. People are tools for that. Technology is basically gadgets. The pioneers, the people who start with any technique, are usually invented. People started with video and digital years ago. They were inventive. We don't know much about them anymore, but they were interesting people. What I don't like is how people follow. I also don't like being imposed with machines that aren't ready, the computers and cameras. But of course you can invent in 3D and IMAX. As long as you can make something called cinema, it's okay.

Beaks: You talk about the frustration of not being able to make a feature for twelve years. Do you foresee having that difficulty again?

Carax: You don't make a film alone. When I say I was lucky to meet Jean-Yves at twenty, I was also lucky to meet Denis Lavant. I met a producer, and if I was able to make this movie HOLY MOTORS, it was because of Denis Lavant and my associate producer - and he died on the last day of the sound mix. You have to meet people. To make a film, you need health, money and people. It's very hard to meet people [with whom] you feel you can make a film, whether it's an actress, a director of photography or a producer. On each film I feel like I'm starting from zero. And on each film I've always felt it's the first and the last. So of course I don't hope this is the last. I hope I'll do another film. But I'm really starting from zero. I don't have any agents, and I don't have any producers. Once you make a film, the projects before are dead. You have to move on to something new. It's exciting, but it's not reassuring.

If you're a producer, and you're not on the phone to Leos Carax right this instant, you're a fool.

HOLY MOTORS is currently playing in Los Angeles at the Nuart, and will begin a run at the Cinefamily on November 23rd. To find out when it'll play at a theater near you, check out the official website.

Faithfully submitted,