2011 kicked off at a ridiculous masterpiece-per-month pace, tailed off over the summer, roared back to life in September with a miracle, and concluded with what could easily wind up being the best film of the decade. It was a phenomenal year for movies, one of the greatest of my lifetime. All, it would appear, is well in Cinemadom.

And then there's this: of the films on my top ten list, only one has, to date, grossed more than $10 million, while none played on more than 250 screens. Four of these movies were subtitled, while one was a documentary about death - commercially, they were destined for obscurity (even though one of the funny-talk movies concludes with an exhilarating forty-minute sword battle). The other five, however, required no reading, featured familiar actors if not outright movie stars, and were "inaccessible" only if you believe audiences are incapable of enjoying a movie on anything other than a visceral level - which I don't. Oh, and one was a crowd-pleasing alien invasion flick starring a bunch of foul-mouthed kids; naturally, its distributor had no idea how to sell it (and didn't even try).

In years past, I might've blamed the studios for dominating multiplex screens or distributors for not devising more inventive marketing campaigns, but availability and awareness is less of a problem now. Many great "specialized" films are now made available nationwide on VOD, usually before they get their limited theatrical run. So movie lovers can send a message to studios and distributors by staying in and spending $9.99 on the well-reviewed 13 ASSASSINS rather than glumly sacrificing peak admission to the widely-panned BATTLE: LOS ANGELES. It's a small, but significant gesture; the more people embrace the VOD option for new, non-mainstream movies, the more likely it is that interesting filmmakers will find financing for their next, non-blockbuster project. Supporting this model is important. If there's so much as a slight decline in theatergoing complemented by a significant increase in VOD purchases for smaller movies, exhibitors might consider dedicating one small-market multiplex screen out of twelve to a non-studio picture. So then, when I cough up a top ten list bereft of one full-fledged studio release, I won't have readers complaining that they never got the chance to see a widescreen epic like 13 ASSASSINS in the theater. (Oh, and it goes without saying that piracy is never an acceptable option. I highly recommend reading these two eloquent essays by director Ti West and producer Keith Calder on the damage done.) Sermon over.

A word on my list: these are the films that I feel succeeded ecstatically on their own terms. In other words, if I see the CITIZEN KANE of cheerleader movies, you best believe that I will rank that film ahead of a hugely ambitious superhero yarn that falls a little short of its lofty goals. Of course, you may disagree. That's fine. No shame in being wrong.

First, the "honorable mentions" (i.e. movies that fell in and out of the last three slots on my top ten)...

DRIVE (d. Nicolas Winding Refn, w. Hossein Amini, based on a novel by James Sallis)

An immaculately shot-and-edited riff on two wheelman classics (Jean-Pierre Melville's LE SAMOURAI and Walter Hill's THE DRIVER), the title suggests a minimalist take on the subgenre, but Refn's film contains a surprising depth of feeling. The narrative trajectory is familiar (Gosling's nameless driver is doomed the minute he lets morality cloud his professional judgment), but the style is exhilarating; Refn dances around on the edges of scenes, often cutting away from obligatory moments to give us an uncommon reaction or odd detail that most directors wouldn't think to capture. He also combines the year's most sublimely romantic moment with its most shocking outburst of ultraviolence. And no appreciation of DRIVE is complete without Kavinsky.

CONTAGION (d. Steven Soderbergh, w. Scott Z. Burns)

A dazzlingly concise procedural that depicts with alarming clarity the micro/macro response to a rapidly spreading pandemic. Soderbergh's film, which improves dramatically on repeat viewings, presents a worst-case scenario but boldly resists blowing it out to apocalyptic proportions. From the perspective of Matt Damon's widower, we get the disquieting ground-level view of a man protecting what's left of his family from a panicked populace gradually running amok. But when we shift to Jennifer Ehle's brilliant CDC researcher, the tone is more invigorating than frightening: while society is busily trying to tear itself apart, the best and brightest shut out the fear-mongering din and save the world. It's a nice little fuck you to today's rampant anti-intellectualism.

MARTHA MARCY MAY MARLENE (w. & d. Sean Durkin)

Girl joins cult, girl flees cult, girl attempts to deprogram without telling anyone in the non-cult world where she's been for the last two years (possibly endangering her sister and brother-in-law in the process). Sean Durkin's masterful debut feature flirts with the familiar, but derives most of its unbearable suspense from delaying or completely eliding the obligatory scenes. Escaping the cult was just the beginning of Martha's nightmare; returning to a life that makes no sense to her, all the while waiting to get dragged back to the compound, is even more confusing and terrifying. Durkin's precise compositions, particularly in the big-windowed lake house owned by Martha's well-off brother-in-law, amplify the horror, but it's Elizabeth Olsen's fully committed lead performance that truly unnerves; we're on her anxious wavelength until she capitulates to her uncertain circumstances in the final shot.

THE MYTH OF THE AMERICAN SLEEPOVER (w. & d. David Robert Mitchell)

As I wrote last July, "David Robert Mitchell’s THE MYTH OF THE AMERICAN SLEEPOVER is a lyrical look back to the pain and possibility of high school. Set on the last day of summer, it conjures up the night-in-the-life yearning of AMERICAN GRAFFITI and DAZED AND CONFUSED, but eschews era-specific nostalgia for a more timeless evocation of those moments in a young adult’s life when everything seems strange and horrifying and kind of wonderful. It is a quiet, deeply felt film, closer to Truffaut than Lucas or Linklater. Mitchell is after small epiphanies, the kind that occur in silences, when we’re afraid to come out and say exactly how we feel."

RISE OF THE PLANET OF THE APES (d. Rupert Wyatt, w. Rick Jaffa & Amanda Silver)

Rupert Wyatt's re-whatever of 20th Century Fox's primate franchise could've been a masterpiece had it been told exclusively from the perspective of Caesar, but let's just be thankful that a movie this subversively skeptical about the future of humanity made it through the studio system with its head and heart intact. Besides, that the human element of the narrative is so unconvincing (save for John Lithgow's Alzheimer-addled patriarch) only makes it easier to cheer on the apes as they battle their way to the Redwoods. All the superlatives heaped upon Andy Serkis's performance-capture embodiment of Caesar are warranted; he does with movement what Lon Chaney did a century ago with makeup.

HUGO (d. Martin Scorsese, w. John Logan)

THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN (d. Steven Spielberg, w. Steven Moffat and Edgar Wright & Joe Cornish)

Two masters take a crack at the 3D format and have a ball. For Scorsese, it's a preservationist's personal journey through silent film history designed to engage young viewers' imaginations while exposing them to timeless feats of entertainment. To that end, the film works beautifully; my eight-year-old nephew was so enraptured by the story and technique that he applauded George Melies at the end of the movie. Yet another youngster bitten by the movie bug. Thank you, Mr. Scorsese.

Spielberg's film is pure escapism, the most joyous spectacle he's concocted since INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM. The story might be a tad ephemeral, but the set pieces are absolutely mindblowing; after the unfortunate KINGDOM OF THE CRYSTAL SKULL, the joy has returned to Spielberg's craft. All of the action sequences are vintage Beard, but the wild chase through a hillside Moroccan village involving everything from a motorcycle to a trained falcon to a runaway hotel is cleanly choreographed, can-you-top-this insanity heightened by an elegant, unobtrusive use of 3D. It's as if Spielberg took all those INDY 4 pans personally.

WAR HORSE (d. Steven Spielberg, w. Lee Hall and Richard Curtis, based on a novel by Michael Morpurgo)

If THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN offers a limitless digital showcase for Spielberg's crowd-pleasing talents, this direct appeal to human decency sends the director back to war, where he rediscovers his unfettered optimism in the bloodiest, and perhaps most meaningless conflict of the twentieth century. Prior to seeing WAR HORSE, I found myself pining for Spielberg to capture World War I in all its grisly, run-down-the-guns absurdity, but his decision to hold back on the carnage in favor of making an old-fashioned epic turns out to be a masterstroke. Most of Spielberg's post-AI films have been downbeat affairs; there's an acknowledgment of mortality that undercuts his inherently upbeat outlook. But with WAR HORSE, he seems to be saying that nihilism is a copout; indeed, this belief that humanity's capacity for good is every bit as strong as its inclination toward atrocity is actually kind of revolutionary.

And now, the ten...

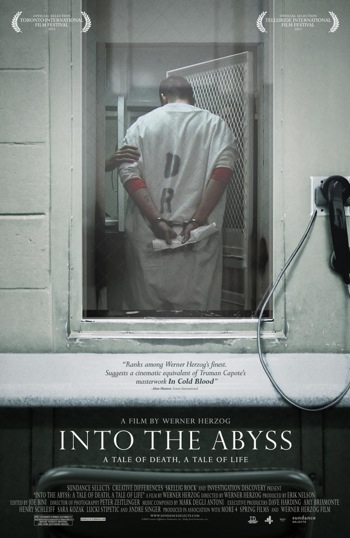

10. INTO THE ABYSS: A TALE OF LIFE, A TALE OF DEATH (d. Werner Herzog)

Werner Herzog's best film since GRIZZLY MAN, and possibly the most devastatingly direct argument against capital punishment I've ever seen (though Herzog swears that this is not an anti-death penalty film). As I wrote last November... "In the prologue of Werner Herzog's documentary, INTO THE ABYSS: A TALE OF LIFE, A TALE OF DEATH, a death row chaplain who administers last rites to the condemned explains how he finds solace in the lush, tranquil beauty of the golf course. He describes how he is moved by the occasional run-in with an animal, even one as insignificant as a squirrel. So Herzog follows up with a question probably no interviewer on the planet would ever think to ask: "Tell me about an encounter with a squirrel." And so he does, recalling a time when a squirrel darted in front of his golf cart, and how he was able to break in time and spare the animal's life. A few seconds later, the man whose job it is to observe the execution of countless prisoners every year is in tears.

"Herzog only had an hour with this chaplain, but he elicited this profoundly moving response by picking up on the man's sensitivities. Why did he single out squirrels? Why not ask? Herzog employs this intuitive line of questioning with all of his subjects in the documentary, and the result is a quietly devastating contemplation on the fragility of life and the finality of death. This is obviously well-trod ground, but by examining a senseless triple homicide committed by two morally adrift Texas teenagers (one of whom, Michael Perry, is scheduled for execution without a prayer of a stay), Herzog emerges with a reasoned and empathetic portrait of a system that serves no greater good."

9. ATTACK THE BLOCK (w. & d. Joe Cornish)

Joe Cornish's remarkably assured debut gained additional resonance after last summer's riots in England. The disenfranchisement, the eagerness to portray London's ethnic youths as mindless, hoodied miscreants... it all flooded out from the BBC, FOX News and pretty much any outlet that values easy villainization over a nuanced discussion of civil unrest. Cornish's sci-fi/horror/comedy hybrid - which finds a group of lower-class kids defending their housing development against an alien invasion - put the mainstream media to shame by allowing its criminal-minded characters to mature once they realize their misdeeds have brought home this extraterrestrial plague. These aren't bad kids; they just don't see the upshot to playing by society's rigged rules. ATTACK THE BLOCK is genre filmmaking at its finest: a fast-paced, cleverly structured yarn on the surface, and a socially conscious commentary on the uncertain future of the country underneath (punctuated by John Boyega's Moses dangling none-too-subtly from the Union Jack before being arrested).

8. TINKER, TAILOR, SOLDIER, SPY (d. Tomas Alfredson, w. Bridget O'Connor & Peter Straughan, based on a novel by John Le Carre)

A miraculous distillation of John Le Carre's classic spy novel, Tomas Alfredson's less-is-more approach requires rapt attention on a first viewing and rewards it handsomely with a unexpectedly jaunty denouement set to Julio Iglesias's rendition of "La Mer". And yet it wasn't until I watched the film a second time that I fully appreciated the filmmaker's strangely off-center approach: given the dense nature of Le Carre's narrative and the condensed running time, you'd expect Alfredson to be all business visually, but he generally keeps his distance - and this refusal to foreground the salient details somehow accentuates the personal betrayals. Gary Oldman's George Smiley comes off as an overmatched dullard for the first portion of the film, but his silence and lack of action is measured; he's just gathering details, studying the chessboard, and waiting for the first errant move. Once he sees the endgame, Smiley patiently proceeds step by step until the board is cleared - but at what emotional cost? The entire ensemble is phenomenal, but Oldman's Smiley is an understated triumph for an actor who's often gone gleefully overboard. He's certainly been louder, but he's never been better.

7. THE TREE OF LIFE (w. & d. Terrence Malick)

This is either seven spots too low or has no business being in my top ten. THE TREE OF LIFE is overthought, personal to the point of obscure, and easily the most affected film of Terrence Malick's career (there are several sequences that make me cringe). But it is also a rich, intellectually challenging, and frequently gorgeous meditation on the meaning of our brief stay in this universe. I think Harry nailed this film when he called it a prayer; with Berlioz's "Agnus Dei" batting cleanup on the soundtrack, you're left feeling sanctified even though you never fully trust the imagery. Is Malick presenting a literal afterlife or an individual resignation (concluding with the heat death of the universe)? If he's expressing a belief one way or the other, I'm misreading his shorthand. But I've never looked to Malick for answers; I'm just thrilled he's pondering the unponderable (with the great Emmanuel Lubezki as his cinematographical guide).

6. UNCLE BOONMEE WHO CAN RECALL HIS PAST LIVES (w. & d. Apichatpong Weerasethakul)

This is either six spots too low or above being ranked. Apichatpong Weerasethakul's lyrical triumph is ostensibly about a man who visits with his loved ones - living and dead - before succumbing to liver failure, but it's really a gateway to an entrancingly visual rumination on man's relationship with nature. And that's as far as I'm willing to go with an interpretation. Weerasethakul's film is inexplicable in all the right ways; the imagery is consistently lush and enchanting, even when you haven't a clue as to what it all means; at a certain point, you either surrender to the film's strange current, or you intellectualize it and break the spell. UNCLE BOONMEE may be baffling at times, but it connects on a deep, dreamy level; if audiences truly value "immersive" cinematic experiences, they'll ditch the big-ticket gimmicks and hop on Weerasethakul's wavelength. Red-eyed apemen > blue-skinned Na'vi.

5. 13 ASSASSINS (d. Takashi Miike, w. Daisuke Tengan, based on a screenplay by Kaneo Ikegami)

From my March 25th, 2011 review... "Based on the 1963 Eiichi Kudo film of the same title, Miike's 13 ASSASSINS is, in tone and sheer physical scale, a stunning departure for the prolific director. It's a invigoratingly straightforward narrative about revenge, honor and the preservation of peace through "total massacre". Of course, there are perverse, Miike-esque flourishes sprinkled throughout the movie, but he's mostly paying tribute to the classical samurai cinema of Kudo, Masaki Kobayashi, Kenji Misumi and, unavoidably, Akira Kurosawa - and, no hyperbole, meeting them on their vaunted level. This is Miike returning to the precise formal control of AUDITION, and it's an inspiring reminder that when he's not indulging every lunatic creative whim, he's one of our most talented filmmakers working today.

"Some have observed that Miike's film works as a wholesale subversion of the samurai picture, but while there's certainly a satiric sensibility at play in the lengthy climactic battle, the central conflict is still, at its core, basically good versus evil. 13 ASSASSINS is a largely conventional movie in which morally questionable men refuse to stand by while an absolute evil (born of unchecked privilege) preys on the weak. Nothing terribly novel here. But it's all carried off with such extraordinary aplomb that it would be foolish to ding it for reveling in its own excess. Does Miike personally buy into any of this? Fuck if I care. All that matters is what's up on the screen - and 13 ASSASSINS is a stone-cold, limb-severin', bull-burnin' masterpiece."

4. MEEK'S CUTOFF (d. Kelly Reichardt, w. Jonathan Raymond)

Kelly Reichardt's latest film about lost people centers on three families led astray on the Oregon Trail by Stephen Meek (Bruce Greenwood), a grizzled guide whose blustery confidence is really just a dead-end mix of pride and incompetence. These people are doomed before the film even starts; they trusted the wrong man, and now they're aimlessly wandering the eastern Oregon desert, vulnerable to attack by Native Americans and in desperate search of drinkable water. Reichardt's film is at once a harrowing depiction of 19th-century westward exploration gone wrong and an indignant allegory for an America trying to find its way after George W. Bush's disastrous eight-year presidency. Aesthetically, the movie is a marvel: shot in old-school Academy ratio (1.37:1) as a means of closing off the expansiveness of the unsettled Oregon landscape, Reichardt's film holds out scarce hope; the best she and screenwriter Jonathan Raymond can offer is Michelle Williams's Emily Tetherow standing up to Meek's brutish imbecility. Unfortunately, most of Emily's party will perish; Meek, the historical record tells us, will live another forty years. (Wanna get mad? Just think of all the dutiful servicemen Bush and Chaney outlived without ever contributing a day of their awful lives to combat.)

3. CERTIFIED COPY (w. & d. Abbas Kiarostami)

In his seventieth year, celebrated Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami turned his gaze to Tuscany and captured one of the most profoundly romantic films I've ever seen. Starring Juliette Binoche as an antiques dealer and William Shimmel as a writer of some acclaim, CERTIFIED COPY combines the walk-and-talk contentiousness of Roberto Rossellini's JOURNEY TO ITALY with the first-date discovery of Richard Linklater's BEFORE SUNRISE, and then, about halfway through, yanks the rug and leaves you reassessing everything you thought you knew about their incipient relationship. What is the real thing? Are these two playing a game? And what does it matter if we can't tell the difference? Once we start doubting the couple's past, we begin to reexamine the very nature of intimacy (i.e. how long you have to know someone before connecting on a meaningful level). I never expected to see a film this supple and sensual from the formally rigid Kiarostami; freed from the expectations (and limitations) placed upon him as Iran's great cinematic hope, he's reinvented himself as a romantic.

2. MARGARET (w. & d. Kenneth Lonergan)

Lisa Cohen (Anna Paquin) didn't ask to be thrust into the center of a tragedy; she was just trying to track down an authentic cowboy hat on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. And she wasn't trying to flirt with that bus driver (Mark Ruffalo) when he blew through a red light and clobbered that poor woman; she just desperately needed to know where he acquired his authentic cowboy hat. Okay, she was flirting a little. And he was flirting back. Granted. The important thing is that she didn't mean to give a false statement to the police; she was just a little upset after that poor, mangled woman died in her arms. She didn't mean for any of this to happen, okay? But she's going to make damn sure that it never happens again.

Kenneth Lonergan's MARGARET is, narratively speaking, a sprawling work about a young girl's reckless pursuit of justice. Lisa knows the bus driver was at fault, resents that he was flirting with her prior to the accident (never mind that she initiated the distraction), and was deeply affected by the dying woman crying out for her own daughter, named Lisa. She also knows from drama (her mother, Joan, is an acclaimed New York City stage actress) and dramaturgy (her father, Karl, is struggling as a screenwriter out in California), which explains how she's effortlessly inserted herself into this small tragedy and blown it up into opera. Lisa's a seventeen-year-old wrecking ball of self-absorption, and she's not going to stop knocking shit over until she feels better about this whole thing.

Lonergan observes Lisa's crusade with the same eloquence and empathy he brought to his masterful feature debut, YOU CAN COUNT ON ME; he finds the humor in her idealistic outrage without making light of it. Lisa may be an emotional powder keg, but the girl can't help it; her body is mercilessly fueling this out-of-proportion response. And Lonergan, rather than rein her in, lets her lash out, trusting that we'll stay sympathetic even as she turns at times into a hormone-addled monster. It's rare to see a teenage girl depicted with such volatile authenticity in an American film (it's easier to make young male rebellion look cool, I suppose); if Lonergan had kept his gaze fixed on Lisa's story, he might've come away with a small-scale masterpiece.

But MARGARET was written at a time when 9/11 was still an open wound for most of the country. It was produced at the moment filmmakers tentatively began to grapple with it. And it languished in editorial/legal limbo while that blow was absorbed, and the country got on with the business of tearing itself apart. It finally arrived in September of 2011 as a rough assemblage of complex ideas that no major studio (or studio boutique) could ever comprehend or, most importantly, market. The barely-available 149-minute cut of MARGARET is an unfinished, under-the-gun collision of sensational sequences; it's so close to being one of the best movies you've ever seen that you want to split the meager difference and place it in the pantheon. There's a longer cut of the film (edited by Lonergan with the input of his filmmaking mentor Martin Scorsese), but the protracted legal dispute that kept the picture shelved for five years could keep that version from ever seeing the light of a projector. Until these issues are resolved, MARGARET is in a class with Orson Welles's THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS as a frustratingly mistreated masterpiece.

1. A SEPARATION (w. & d. Asghar Farhadi)

It's possible that the censorial dictates of the Iranian government forced Asghar Farhadi to structure this drama of marital discord as an even-handed, everyone-has-their-reasons narrative, but this kind of empathy is rare regardless of one's nationality. As a writer, Farhadi has drawn dangerously lofty comparisons to Ibsen and Chekhov, but his dextrous depiction of a country that is failing its people ranks as one of the all-time great balancing acts - if only because he's not in jail.

A SEPARATION is just beginning to open in theaters across the country, and it's my hope that Sony Classics will spend to get the film seen by as many people as possible. There's a dangerous drumbeat to war with Iran echoing out at the moment (much of which is predicated on their troubling development of a nuclear weapons program), but most Americans don't have the slightest idea about the struggle of its citizens. When a film like A SEPARATION arrives, replete with devastatingly nuanced critiques of the country's theocratic system, we're getting a distress signal from an oppressed people. I adore A SEPARATION as a human drama, but I get outraged when I consider that a significant portion of the United States wants to bomb ordinary Iranians into submission. I've never spoken with Farhadi, but I get from his film that there's an immediacy beyond the personal; this is a movie quietly focused on creating a cross-cultural dialogue. A SEPARATION doesn't have the first thing to do with war, but I've seen the film twice now and I despair at the notion of killing people eager to effect change, but reticent to sacrifice when history tells them the world just doesn't care.

One of the greatest films I've ever seen just escaped from a dissent-squashing dictatorship. This is a call to discourse. This is why film - all ticket-hiking gimmickry aside - still matters.

Faithfully submitted,