There’s a moment early in Steven Soderbergh’s CONTAGION where a brilliant CDC researcher (Jennifer Ehle) talks her boss (Laurence Fishburne) through the complex DNA structure of a newly discovered virus. It’s a jargon-heavy dialogue between two big-brained professionals, the kind that, in most movies, would conclude with an exasperated government official cracking, “In English please?” But this obligatory exchange is unnecessary. We’ve just spent twenty minutes or so buying into a very real world populated by a lot of very smart people who are scared shitless by a highly contagious virus they’ve never seen before. If they’re concerned, we’re concerned; and if they’re having to figure it out on the fly, we’d rather scramble to keep up with them than have the mystery artlessly snuffed out by some dumbed-down, trailer-friendly quip.

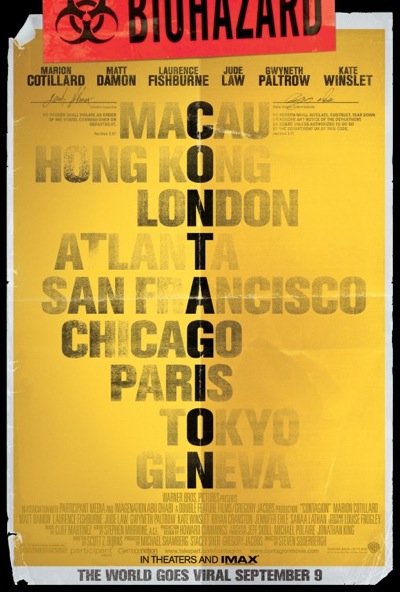

Though Soderbergh has joked that CONTAGION is his take on the star-studded Irwin Allen disaster films of yore, it’s sensational only in its bold belief that audiences are eager to be treated like educated adults. Working with screenwriter Scott Z. Burns (THE INFORMANT), Soderbergh has delivered a sharp, economical procedural that immerses us in the ground-level horror of a rapidly-spreading pandemic while also involving us in the frantic search for a vaccine. Soderbergh expertly shifts from one perspective to another, giving us a full sense of how such a lethal event would play out at nearly every level, from personal to global. It’s an absorbing, strangely exhilarating film - possibly the director’s most accomplished work since OUT OF SIGHT.

It also, until a week ago, looked as though it might be one of his last works. Thankfully, Soderbergh has put to rest rumors of his impending retirement from filmmaking; he just wants to take a break, try his hand at painting, and, basically, “recalibrate”. Most likely, he’ll be back. But before he hits pause on one of the most eclectic directing careers in the history of cinema, he’s still got three movies to finish: MAGIC MIKE (based on Channing Tatum’s experiences as a male stripper), THE MAN FROM U.N.C.L.E. (based on the cult TV show) and LIBERACE (an unlikely biopic starring Michael Douglas in the title role).

When I sat down with Soderbergh a couple of weeks ago at the CONTAGION press day in Los Angeles, he candidly discussed just about everything but his planned sabbatical. A significant chunk of the interview concerns his filmmaking process on CONTAGION, and how it’s changed – and will continue to change - with the advent of new technology. We also touched on his scrapped Leni Riefenstahl biopic, his longtime collaboration with composer Cliff Martinez, what happened with MONEYBALL, how he feels about CONTAGION being blown up for IMAX, the uncertain filmmaking future for today’s burgeoning auteurs and much more.

Before I could hit record on my iPhone, Soderbergh started grilling me about the inner workings of Ain’t It Cool News. This led to a back-and-forth on the state of entertainment journalism, which is where we’ll start the Q&A…

Steven Soderbergh: You know, what’s my filter? When I’m the target for so much information now, what is my filter? How do I delineate between something I should be taking seriously and something I shouldn’t? I mean, that’s where you can help.

Beaks: Well, you can do your job. You can be well researched and try to be accurate. That’s the way I try to approach it. But so much of it is about generating traffic and page views. For most sites, it’s definitely a tabloid type of thinking rather than getting the story right.

Soderbergh: Well, that’s the thing. I see a lot of stuff where I just feel like… because sometimes I have information that isn’t immediately accessible to someone like you, but is not inaccessible. And I’ll see something put up and I know “Boy, they just didn’t follow this up. There’s a real story there, and somebody just accepted what they were told and didn’t go anywhere past that.” In a lot of cases for some sites, I know it’s because there’s a bias toward people who give them information, and so they don’t want to dig too deep because they don’t want to alienate their source. I feel like “Well that’s fine, but that’s not journalism.” When you are just protecting your agenda, and you exclude anything that doesn’t line up with it, you can have a site and all of that shit, but you can’t sit here and tell me that you are a “journalist” by my standards. The biggest one is budget numbers. The numbers I’ll see somebody quote from a studio - “This movie cost X” - and it gets printed… I’m like “You’ve got to be kidding me! You said that with a straight face and somebody went ‘Okay?”

Beaks: In terms of the budget being too low?

Soderbergh: Oh yeah. An unnamed movie that came out this summer, a studio floated a number that I can’t believe anybody who knows anything about movies took seriously, and they did.

Beaks: Generally, I assume whatever number they are giving us [for a big summer movie], I can tack on $50 million.

Soderbergh: Pretty much.

Beaks: It’s not a knee-jerk reaction, but--

Soderbergh: No, you can look at the trailer and go, “Uh, I don’t think so.” It just bugs me because I’ve always said what the number is. I think we should out people that are egregiously inefficient. There’s a lot of it. The studios… often their entire process is pretty inefficient, but there are a lot of filmmakers out there too that are just totally out of control, and I feel like “You are polluting the environment. You are making it harder for the rest of us. Because we all get tarred with that brush when you go out and you go wildly over-budget and wildly over-schedule, and are sort of flippant about it. Then the next person that walks in the door pays the price for that. It’s not cool.”

Beaks: So as a filmmaker who tries to be responsible, you kind of know the parameters in which you can work and where you can deliver a film for a certain price. But we’ve heard lately from Disney that “It’s not about story, it’s about spectacle. We don’t give a shit about story, spectacle is what we are trying to deliver.” I guess it depends on what kind of a film you want to make, but when you are dealing with studios, they are disinterested in making, like, moderately-budgeted dramas. If you were making KING OF THE HILL today…

Soderbergh: Well, you couldn’t. I mean, that was an $8 million film back then. Yeah, you just couldn’t get that film made today. That’s just not going to happen. Look, I get it, but I think… it’s cliché, but it’s true: at the end of the day, all the audience really does care about is the characters in the story. We’ve seen too many examples of just spectacle, with more attention being paid to the spectacle than the story and the characters, that have flopped. I don’t know how many more of these we need for this to be proven that, more often than not, that’s what people come out of the theater remembering.

You have to give credit to Warners for not hesitating to say yes to this movie when, by design, we were kind of moving against the grain of what’s typical for a film about this subject. On the one hand, did I go in and pitch it and say, “It’s about hope and scope”? Of course I did! But at the same time I made it clear, “Look, we are not going to be doing a lot of the stuff that people usually do, like cutting to a city we have never been to, cutting to a group of extras that we don’t know just in order to create more scale. I’m not going to do that. If our character hasn’t been there, we are not going there.” And that’s, I think, a good rule if you are trying to make the movie the way we were making it. But it forces you to think laterally instead of vertically, and fortunately they were cool with that.

So I look at it and I think, “Sixty million bucks is a lot of money.” And then I see a contemporary comedy shot in Los Angeles that cost more, and I can’t figure out why. So I’m always trying to balance the idea versus… especially after THE GOOD GERMAN. That was a frustrating experience just because I look back on that and… I misjudged the accessibility of that idea, or the level of interest in the idea of that movie, and I should have figured out a way to make it a lot cheaper. None of us got paid a lot of money; it all went into the art department. I look back on it and go “If the movie cost $32 million, I should have figured out a way to make it for $14 million.” I don’t know what that would have been or if it had been possible to do it the way that I imagined, but I clearly misjudged the commercial potential of that idea and I don’t like to…. it’s not that I don’t like to fail, I just don’t like to fail and then learn nothing. I feel like “Okay, I learned a lesson there. I’m not going to do that again.”

And [CONTAGION] frankly was born out of a process of my learning that lesson. Scott [Z. Burns] and I were about to go into meet with Michael Shamberg and Stacey Sher to close the deal to make a movie about Leni Riefenstahl. They had the Stephen Bach book, which is very good. Scott and I had a really, really interesting take on this, like a very radical interesting take on how to do this, and we were supposed to meet to talk about the pitch, like “Here’s what we are going to do.” And suddenly I go, “I don’t want to do this. Nobody is going to go see this.” I go, “We are going to spend twenty-eight million bucks and two years of our lives, and nobody is going to want to see this, not even our friends. I’m not going to do it. I’ve done that. I don’t want to do that again. I’m too old.” I literally said [to Burns], “What else have you got?” And he goes “I want to do an ultra-realistic pandemic film.” I said, “Let’s go pitch that instead,” and that’s what we did.

Beaks: Now the Riefenstahl biopic: was that a realization of you make that film and--

Soderbergh: “Who’s the audience for that? At $28 million, who’s the audience for that?”

Beaks: But that’s an “awards film,” right?

Soderbergh: Hey, you can’t assume that. I’ve made that mistake before, too.

Beaks: Sure, but isn’t that what the studio thinks? Isn’t that how you then get them interested?

Soderbergh: I don’t care at that point. It’s really about what I think, and I think “Can’t count on that at all. Can’t count on the critics. Can’t count on anybody.” I’m not going to make that mistake again, I’m just not. Again, when I was younger, when I was in my twenties… I look back at KAFKA, which creatively doesn’t really work. But I look back on it, and I smile in the sense that, like, that’s a film that only a stupid young man could make - and I mean that in a good way. You have to be twenty-eight to think that you are going to pull that off. So that’s fine. But if you keep making that mistake over and over again, you are an idiot. So [the Riefenstahl biopic] felt like that, even though I felt we had a really interesting approach, it just felt like a long haul; it’d be like running a marathon and falling down at mile twenty-five, you know? It just didn’t feel like it was going to result in anything that I was going to be satisfied with. The good news is I learned my lesson, we shifted gears, and now we have [CONTAGION], which I’m really happy with and I think plays to my strengths, and also, at the same time, is a world I haven’t explored before. It’s a world that really works well in a movie.

Beaks: I know ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN is a favorite film of yours, and this is kind of an investigative…

Soderbrgh: Yeah, it’s a procedural…

Beaks: It’s a procedural where there’s a lot of information flying at the audience, a lot of jargon that we don’t understand, but there is something thrilling…

Soderbergh: The context. You know they know what they are talking about.

Beaks: Exactly. That’s exciting. You are there with them trying to figure it out. And even when you can’t, their level of concern and the respect that we have for their knowledge, we know the situation is dire.

Soderbergh: It’s exciting to watch people who are good at something on screen, it just is. It’s why THE DAY OF THE JACKAL works. There’s no reason that movie should work the way it does, and it’s because even though Edward Fox is a mercenary assassin, he’s so fucking good that you find yourself rooting for him. I mean, it’s wrong. He kills people. But he’s just so proficient, and we have a real attraction as an audience to that kind of proficiency. When we were researching this, Scott and I just really got pulled in by these people who do this for a living, and it was fascinating. They are smart and they work hard and the stakes couldn’t be higher. They were impressive. I mean the film really shifted a bit during the research phase because of how we responded to them.

Beaks: And it allows you to play around within a genre and a subgenre, the disaster film and the epidemic thriller. I was trying to track down the first epidemic thriller. Maybe PANIC IN THE STREETS is the first kind of film like that.

Soderbergh: Yeah, I think so, and a really good movie, too.

Beaks: I agree. Did you go back and look at it?

Soderbergh: I did. Scott didn’t, which was fortunate. He just watched it recently, and he goes “Boy, I’m so glad I didn’t see this, because there are so many things that are similar that I would have gotten worried.” But, yeah, I liked the idea that it was kind of a horror movie at the same time. I kept throwing the word “intense” around to Warner Brothers, because they kept asking, “Is it a thriller? What is it?” I just said, “Look, it’s just going to be intense. That’s all I can tell you.

In addition to the rules that we set up about the writing, when we started to shoot I had my rules about what I was doing with the camera and what I wasn’t doing with the camera. The whole movie is shot with two lenses, basically an 18mm and a 35mm. Very clean compositions, very symmetrical, very unobtrusive, nothing that calls attention to itself, camera can’t move unless an actor is moving… I really wanted the style to be really, really simple. Not boring, but simple. Clean. I wanted every shot, every cut, to have a reason - nothing extraneous, no waste at all. If you pulled one shot out, then the scene wouldn’t work as well, and if you added one shot you would make it also not work as well. I was trying to be really rigorous about it, and I’m happy with that. I feel like it’s as efficient in its own way as the virus is. It’s moving very clearly in a certain direction.

I like having restrictions. I like having rules of things that you can’t do, and I see a lot of movies in which somebody has never had that conversation with themselves. I look at them and I’m like “None of this is unified. You’re just doing shit that doesn’t even make sense on its own terms. You’re going from this lens to that lens, the camera is moving, it’s not moving, it’s a point of view, but then it’s not…” I just go, “This is just incoherent aesthetically. And it drives me insane because I feel this is stuff you can learn in an hour. I’ve given lectures about directing in which, in an hour, I lay all of this out for you if you need to know it.” So it drives me nuts. This has become like the best entry-level job in show business, directing a movie. It’s crazy.

Beaks: It’s been said that oftentimes the person who knows the least amount on a film set is the director.

Soderbergh: Sometimes. It’s also amusing when you are confronted, as you are inevitably, with the fact that everybody on the movie is making their own movie, when it really dawns on you that somebody who is working in this department is making something completely different than you are – or at least is imagining it. (Laughs) That always cracks me up.

Beaks: How do you rein that person in?

Soderbergh: I don’t, unless we are going to have a head on collision. Sometimes it’s what keeps them going, and I don’t want to rain on their parade as long as it’s the right parade, and that we are marching in the same direction. But it is funny when somebody says “Well this is what I had in mind: that this is happening and this scene is about this.” And you think, “Wow, really? That’s interesting.”

Beaks: You have said this is kind of a thoughtful Irwin Allen type film, but, again, as you were talking about just being very efficient and very focused, you don’t have scope for scope’s sake. So, for instance, you don’t just cut to the President.

Soderbergh: Right, yeah. That’s a good point. That’s another rule of ours, not showing the president. “Can’t show the president.” I set this down: “Okay, the only circumstances under which we can show the president is actual footage of the president talking about H1N1, or something that we could then make it look like he’s talking about our movie. Or we don’t show him at all.”

Beaks: Well it looks like there’s a scene where Fishburne and Ehle are speaking to various heads of states in a teleconference.

Soderbergh: Yeah, and that’s the day-to-day reality of those people, is they are talking to their equivalent in another country. That’s how it happens. We had one scene that we wrote of Laurence, where he was in a van with Jennifer Ehle and Bryan Cranston being driven on to a tarmac, and they are talking about what’s going on and what the next couple of weeks are going to be like. He gets out of the van, and we pan over and realize the president has obviously flown in, and they are going to meet on the plane. That was as close as we ever got to actually acknowledging that there’s a president. But then we both decided, “No, we don’t want to do that.”

Beaks: Because you work as your own DP, it allows you to work quickly. It seems that working quickly is a really important thing for you.

Soderbergh: Yeah, working efficiently. Matt [Damon] talked the other day about the ER scene; when we showed up to shoot it, he had some real questions about how we were going to do it, and I realized, “Okay we can’t shoot this as written right now because we have some real questions.” So I just stopped everything and sent everybody away, and it’s just me and Matt and Scott talking about “Okay, how do we want to change this?” And then we brought in the ER consultant in, and asked him about how he tells people [loved ones have died], and then that’s what we went with. I’m all about moving quickly as long as we are getting stuff that I think works and is good. But I’m the first person to completely shut it down if I feel like we don’t have it - and it’s because we are so efficient that I can do that and still make my day. I’ve done that. It happened a couple of times on some of the OCEAN’S films, where I was having difficulty figuring out how I wanted to approach a scene visually, and on one occasion I literally sent everybody home for the day and said, “I really need to think about this. I haven’t figured this out.” I don’t want to shoot something I know isn’t any good, and I’ve realized that forcing it doesn’t work. The good news is once you have figured it out, it goes very quickly. I sent everybody home, figured it out that night, we came in and we were done by lunch.

Beaks: And everyone trusts that you are going to figure it out?

Soderbergh: Yeah. It’s one of those things that’s sort of a Jedi mind trick on yourself. Once you have jumped out of the plane and you realize the parachute is not going to open… once you’ve reconciled yourself to hitting the ground, and you are okay with that and you are at peace with that, then the parachute opens. It’s a weird thing, you know?

Beaks: I’m kind of curious, because Matt talked yesterday about how at the end of the day you guys kind of got together in the bar, and you were on your laptop and cut the day’s scene together. Do you shoot much coverage?

Soderbergh: No.

Beaks: So you’ve got a pretty solid sense of how this scene is going to play out, and how much time you need to get it?

Soderbergh: I’m trying to figure out how few shots I can do it in, not how many.

Beaks: Right, but then how many takes do your actors need to get what you want?

Soderbergh: If the text is right and you have cast properly, unless there’s some technical issue - it’s a move that requires a certain amount of synchronicity of elements - if you are going more than three or four takes then… I don’t know, I get bored. I don’t think there’s a single shot of Julia [Roberts] in ERIN BROCKOVICH that’s more than three takes.

Beaks: Obviously you want actors who are able to deliver as quickly as that. But have there ever been actors whose work you really admire that you can’t work with because they need lots of takes? Or do you think that you can direct them to get what you want?

Soderbergh: Well, I’ve only have to replace an actor once. You tend to know who those people are and you can usually tell by talking to them to find out who they are. But, yeah, there are certain people that have their reputation of wanting to really chew it over a lot and who really want a lot of takes, and, yeah, I tend to steer clear of them. Like I say, it’s not because I don’t care; it’s just because I feel like “If the scene is right and you are right, then I don’t know why this is taking so long.” There’s one shot on [CONTAGION], I can’t remember which one it was, that we got up into the twenties. There was a lot going on that had to be sort of coordinated - and you know how you do it, and you stay there until you get it. But that’s rare for me.

Beaks: How do you feel about directors like Kubrick or Fincher, people who require, like, seventy takes to flatten out a performance?

Soderbergh: They are obviously looking for something or see something that I’m not looking for and can’t see. It’s all about your metabolism, and that’s just not my metabolism. I don’t get good results by taking more time; I get worse results. I learned that over the course of my first four films that I get better results when I treat it like a sport, where I have to react and make decisions quickly and move on and I’m very cut and dried about that. I make choices on the set and stick with them, and if they are wrong then I try and figure out how to fix them later. But I believe that you should make choices, so… I don’t know. Those guys are termites.

Beaks: From what you then cut together day-to-day on set, how much do those scenes change in postproduction?

Soderbergh: It depends. What I’m doing is trying to get a sense of whether or not we got it, or whether or not I need to go back and get something else. Sometimes you look at it and go, “Well, now that I have this, I really don’t need that other scene; a redundancy has become apparent.” And it’s also just a way of letting, in this case, [editor] Stephen Mirrione know that I’ve taken a very quick pass at it, and then I post it, and I expect him to come in and really finish it. Or in some cases I’ll just dump stuff in his lap and go, “I’m not happy with this. Figure it out. Fix this.” And he does. I just love that the technology exists now that I can get some answers that quickly about what we did. I think of how much better some of my other movies might be if I had that work flow. For me, it’s a really fun way to work.

Beaks: Would that process have helped you on THE UNDERNEATH?

Soderbergh: I don’t think anything could have helped that. But on almost any of them, it would have been nice to be able to see it that quickly and know “I should get another piece of this or another piece of that” before we left a location - because it’s expensive to go back. But it is what it is, and at least now we know we have it. It’s hilarious. It’s like everything else in the world. I mean, I’ve got all of the material two hours after we wrap, ready to cut, and I’m still texting Corey [Bayes, first assistant editor] going “How much longer?” It’s kind of awful. (Laughs) But again there’s more technology coming. On the next movie, there’s stuff that has happened in the interim, like he will be able to get it to me faster. It’s great.

Beaks: This film is kind of a globetrotting thriller. I remember how you shot TRAFFIC using the different filters to tell the audience where they were location- and story-wise. In CONTAGION, though, it’s all pretty much a uniform look.

Soderbergh: It’s more subtle. We were doing stuff, but in a much less obvious way. We had different color temperatures and filters for each of the environments, but I didn’t want it to be as extreme.

Beaks: It worked. I knew were I was at all times and was never scrambling to figure anything out.

Soderbergh: It’s much more subtle, like color temperature in Minnesota is different, the saturation is down, Hong Kong is very warm with a lot of saturation, San Francisco low con filter with a little bit of a bloom on it, London tobacco filter, Geneva lime green… I didn’t want to have it feel like TRAFFIC in that regard. But I did want to do stuff to make you feel like you knew where you where even if you couldn’t articulate why.

Beaks: Having done this on CONTAGION, do you think “Hey, maybe I could have dialed back on [TRAFFIC]?”

Soderbergh: That was fine for [TRAFFIC] and [CONTAGION] was different. Like I said, except for the Gwyneth [Paltrow] flashbacks, there’s no handheld in it. We are never off the tripod or off the dolly and so that immediately sets it apart from TRAFFIC. We were doing something different. I think that shit worked then, and now it’s eleven years later. And that’s the thing with handheld: I don’t know where to go with that anymore. There are certain times when it’s appropriate in terms of having made a couple of movies in which there’s a lot of it, but I’m not sure what to do with it anymore. It formed a very specific function in this as being inside of the video that Marion [Cotillard] was looking at; it was there for a reason. In general, I’m more drawn now to a more classical sense of composition and cutting.

Beaks: Do you just kind of get things out of your system quickly? In other words, do you get bored quickly?

Soderbergh: Yeah, with some things. There are clearly some things that I will never be bored of stylistically, and then there are other things that I feel like “I’ve played this out and I don’t know what else to do with it.” It’s really… here’s another rule: “No helicopter shots.” I don’t know what to do with a helicopter shot that hasn’t been done, and I’m not just going to put a helicopter shot in for the fuck of it. That was another rule in my mind before we went to make the movie: “no helicopters.”

Beaks: It’s the laziest type of establishing shot, isn’t it?

Soderbergh: Well, I get what it can do, but I feel like I can’t just do that. I can’t. The only things I can think of to do with it probably aren’t appropriate for the movie, like something that is so unusual and you think “Yeah, I haven’t seen that before, and now I know why.” But on the other hand, there are certain kinds of compositions that I’m always going to be drawn to that I really like. At the end of the day, whenever I think of a movie, any movie, I see a face. That’s what I see: I see a face with a certain expression on it; that’s what I’m working from. So you know I always work back from that, and remind myself that, again, that’s what people respond to. They don’t respond to shots - not in an emotional way. They may go “Hey, that’s a nice shot,” but it’s faceless. It’s like eyes. They want to see an emotion.

Beaks: Actors are very willing to be deglamorized when they work with you. It seems they trust you. The shots of Gwyneth, allowing her scalp to be sliced open.

Soderbergh: Yeah, she was into it. I think it’s easy to be into that when you are beautiful. (Laughs) People know she’s beautiful. But to her credit, she didn’t bat an eye about any of that stuff: the seizing out, the autopsy… no, she was into it. She was like “Yeah, great!” And I loved it. It was so cool.

Beaks: Speaking of that shot, I was shocked that you got away with a PG-13.

Soderbergh: I was, too - especially since we’ve got it at an R on HAYWIRE, and I can’t figure out why, so are resubmitting. I was prepared to get an R [for CONTAGION], but honestly felt we shouldn’t. There’s tough stuff in it, there’s intense stuff in it, but it’s real and I think a young teenager seeing this movie, there’s plenty in there for them to chew on. It’s a grown-up movie, but it’s also… I know when I was young, it was something that at thirteen or fourteen I would have really liked.

Beaks: Yeah, and it’s something that, again, I don’t think we get enough now. No one knows how to make a good adult thriller for a reasonable budget with those actors, and then trust that a studio will be able to sell it.

Soderbergh: I think everybody was sort of going off their gut in a good way. Like I said, there was just this sense of like “This is good movie material. This is stuff movies do well.” And [Warner Bros.] have been very bullish on it; they moved the release forward because they really felt like “Why wait? We’re going to [the Venice Film Festival]! Let’s come out right after Venice.” People seem to like it. The early toe-in-the-water screenings were really positive, so they were like “Let’s go!”

I’m really happy about the IMAX thing. I’ve seen it in IMAX. Talk about “intense”. Dan Fellman, the head of distribution at Warner Bros., floated this a couple of months ago; he was like, “What do you think about IMAX?” Like most people, I thought, “Isn’t that for effects movies and stuff?” He said, “Look, they would like it not to only be about that. I’ve talked to them about it, and they are interested.” [IMAX] doesn’t do everything. So [Fellman] said, “Can I have a test done for you? Go look at the test.” And I looked at the test and I thought “This is fantastic!” It just makes everything more intense, like the sweat on people’s faces. It was awesome. (Laughs)

Beaks: Seeing it that way, do you then kind of wish you’d composed certain shots differently?

Soderbergh: A couple things I would have done differently. What I realized in this sort of extremely wide tableau… it’s a sad fact of life that everything looks better shot wide open on a lens - which is hell for the focus puller, but that’s just the way it is. It gives you more depth and it just looks better. What I realized looking at it in IMAX is in some of the tableaus, where people are fifty or sixty feet away, that now I would know if I were going to have a movie in IMAX, I would shoot that at a 4.56 to get a heavier stock to create more sharpness at the focal point. Shooting wide open and focusing on something that’s sixty feet away, you can’t really tell you are shooting wide open unless you’ve got something right in front of the lens as a cutting piece. So I did come away going “Okay… if MAN FROM U.N.C.L.E. ends up being something that’s appropriate for IMAX and I’m shooting at a tableau, I’m not going to shoot it at a 1.3. So that was helpful. That was good to know. I was stunned at how good it looked, though. I mean that’s a testament to the MX sensor on the Red. It’s beautiful, like velvet. Just fantastic.

Beaks: I’ll have to see that. And since you brought up U.N.C.L.E., would you consider shooting some of your action sequences in IMAX?”

Soderbergh: Shooting in IMAX? No. No way. Those cameras are too fucking big, especially with the [RED] Epic now, which is a 5K capture. No, not at all. But I will definitely shoot my tableaus with that in mind. They are supposed to show me a test today too, because the format is a little taller than 2.40, and we are shooting that in anamorphic. I want to get a sense of… He’s going to show me some 2.40 films that they have made adjustments to to see if I feel like I’m cropping too much. If it’s not too much, I have to go in basically and sort of recompose shot by shot so I’m not losing information. But, boy, I really got sold on the format. Also, as Danny Fellman was saying, he goes, “Look, those are the best rooms in any complex. The IMAX screen is the best screen, and I want us to be on the best screens.” That’s why he thought of it, and I think he really is on to something.

Beaks: Looking back at your collaborations with Cliff Martinez…

Soderbergh: It’s been a while, yeah.

Beaks: It’s been amazing, especially with SOLARIS, which I think is one of the great scores.

Soderbergh: It’s really good.

Beaks: As you shooting and roughly editing the movie, are you beginning to hear what Cliff might do with the score?

Soderbergh: Absolutely. What was hard for Cliff on this was I changed course with the temp score a couple of times, and that’s really terrifying because his window of composition was not that long. So as we approached his period where he was going to get to start writing the music, and the fact that I kept completely changing this aesthetic of the temp, that was a little alarming for him. But eventually it ended up being a combination of the two [temp] scores in a weird sort of way. I’m really happy with it now. I think he really found this sort of hybrid that serves the movie in terms of keeping the energy level going, but also being atmospheric when I needed it to be a little subtler - yet in those moments still having elements that keep it connected to the energetic part of the score. Even when he’s using the orchestra, he’s got sort of electronic tonal elements that still are connected to the stuff that’s more propulsive, so you never feel like “Oh god, we are in a different movie now.” So I’m really, really happy with it. I think it’s one of his best efforts. The movie is unimaginable to me without it, especially the ending. I love that cue at the end where we sort of see the loop closed. It’s just nice.

Beaks: Having talked about how much fun it is to write dramatically-effective jargon, was that an itch you were trying to scratch with MONEYBALL?

Soderbergh: Yeah, well, I mean I like that stuff, you know?

Beaks: That seemed like a natural fit for you, given how much you like baseball. Thinking how you could’ve had fun playing with the idea of sabremetrics… I’ve got to say I was hugely disappointed when you came off that movie.

Soderbergh: Yeah, there was a lot of that in it. (Laughs)

Beaks: And is that why they were reluctant to make your version?

Soderbergh: I don’t know, but there was a lot that in it. I was fascinated by it because there were real world applications. It wasn’t just abstract ideas, and the line of data mining to result was very clear and, I thought, really fascinating. But, yeah, I don’t know what they ended up with. I guess we will all find out.

Beaks: Okay, so you’re still producing.

Soderbergh: I used to.

Beaks: But you’ve got Lynne Ramsay’s [WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT KEVIN] coming out this year. I’m just thinking about the younger generation of filmmakers who are trying to make interesting movies, but who are having trouble getting across that threshold. I think of people like Shane Carruth, Lynne Ramsey, Maren Ade… what’s your sense of where these filmmakers are going to be able to go? Are they going to be able to continue making the kinds of films they want to make, and, eventually, maybe get to the place where you are today?

Soderbergh: I don’t know. It’s harder now than it was when I was at their stage, it really is. It’s a tough question. I mean part of the mandate of Section Eight [the since-shuttered production company Soderbergh launched with George Clooney in 2000] was to pull those people into situations where they getting more resources, and they were being given projects that had bigger budgets and had stars in them. That was the best part of having that company. Unfortunately, we were kind of getting punished by our success in the sense that the workload became so extreme that we just couldn’t handle it anymore. We had so many things going on that both of us just felt… we had day jobs and we were trying to do this on top of it, and we didn’t want to be producers in name only; we really wanted to do the work, and there just weren’t enough hours in the day. It’s unfortunate that there isn’t another place like that for people like that to go. Lynne was somebody that we talked to back when that company existed; Shane was somebody we talked to back when that company existed. We were tracking interesting people and trying to see if we could find something that either they had that we could pull in, or that we had that we could pull them onto.

But part of having a career is figuring that stuff out. I had to. I reached a point where, pre-OUT OF SIGHT, I realized, “Wow, half the business is off limits to me. I don’t like that. That seems dumb. That seems like not a good career trajectory.” So when OUT OF SIGHT showed up, I thought, “Okay, I know how to do this, and I need to do this. I want to do it. I can do it.” And that opened up the other half of the business for me. I didn’t want to be in the art house ghetto for the rest of my life, and I don’t think anybody does. You want to be able to have a big canvas once in a while. There are some really talented young filmmakers out there, so I don’t know. I don’t know. I hope they like comic books.

That's optimistic.

Steven Soderbergh’s excellent CONTAGION opens wide Friday, September 9th. Do not miss it. And if you live in the Los Angeles area, you should absolutely hit up the Cinefamily this Saturday evening for KING OF THE HILL, which will be followed by a live Q&A with Soderbergh, Jesse Bradford and Amber Benson!

Faithfully submitted,