Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

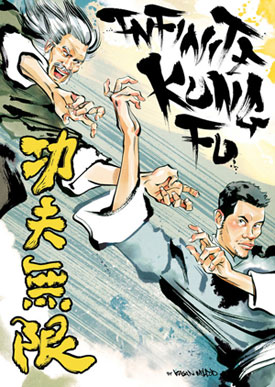

Graphic Nove Spotlight: Infinite Kung Fu

by Kagan McLeod

Premiering for Top Shelf at San Deigo Comic Con

Wide Release on August 9th

First 250 Pages can be read here

Like the movies that it emulates, Infinite Kung fu's plot winds a wildly convoluted route that never the less follows formulaic paths between its twists. An evil emperor sends out his armies to gather the pieces of armor that will grand him the form he needs to seize dominion over Earth. Lowly soldier Lei Kung has had enough of this foraging, so he sets out on his own. On a snowy field, while carving apart the area's local zombie hordes (yes, there are zombies), he happens upon a fat, Laughing Buddha-ish figure meditating. Lei Kung tweaks the man's ear and not finding a response or pulse, does what he things is the good deed and cremates the frozen man. One of the dispatched zombies then rises up and the now benignly animated dead begins berating Lei Kung, informing him the apparently frozen hermit had been mediating for nine years, that Lei Kung's poke halted an attempt to achieve enlightenment, and that now, Lei Kung must be taught what he needs to know become a spiritual replacement. So, Lei Kung begins a journey of reading his way up a tower of books, training in the Shaolin temple and the like, because, as Moog Joogular' points out (yes, there is a particularly funky kung fu great with a lizard inspired detachable limb style named Moog Joogular), "Lei Kung, the greatest kung fu I've ever seen was from you - in the future!"

I should be talking kung-fu, but allow me to talk samurai for a movement, because it's indicative of how I don't particularly trust comics inspired by Asian action movie genres. I don't read them all, or even many of them, but I do read about samurai based English comics. I'll read some interview with a writer pf some comic about a revenge driven swordswoman. The interviewer will ask what works inspired the comic, and the writer will answer "Lady Snowblood;" at which point, I think to myself "yeah, I saw Kill Bill too." Mention Red Peony Gambler or Satan's Sword or something along those lines and I'll perk up. "Lady Snowblood" sounds like your mixing a drink using an prepackaged margarita flavor additive. A silly putty impression would be bad enough, but there's some pretty confused works out there. I think at this point, a Western produced samurai story ought to have a more specific notion of the genre and its cultural context than just "feudal Japan."

On one hand, Infinite Ku Fu opens with a group of kung fu movie legends interacting with actual, legendary legends, as a group of martial artists anger their teachers from the Eight Immortals by revealing that they've taught themselves martial arts from the five forbidden Deadly Venom styles. Promising, but not necessarily checkmate. Drunken Master (a movie that prominently alludes to the Eight Immortals) and Five Deadly Venoms are genre fundamentals. Evoking them doesn't establish that you're the master.

On the other, Infinite Kung Fu kicked off its individual issue run in 2002, so that's before Tarantino stuck a Shaw Brothers logo on the opening of his monumental homage and introduced Gordon Liu to the mainstream, though after the Matrix's massive grab.

In general, it's fair enough to try to capture the appeal of another genre, even if you're crossing language and media. In art and storytelling, grabbing something that demonstrably worked elsewhere is routine. It's also fraught. You have to remember that Frankenstein stitched together his monster from what he thought was well constructed pieces only to find the newly joined whole to be hideously malformed.

This comic plays chicken with the Frankenstein's monster pitfall. Ultimately, its chimera of kung fu movie tropes and undead, and eastern legend and western exploitation movies isn't exactly an elegantly engineered beast, but it is an awesome one.

In one sequence, Moog duels The Emperor’s subordinate master of the Centipede Poison art, a style that causes victims to vomit bugs after being struck. After Moog's apparent death at the hands of the Centipede general, Lei Kung and Moog's protégé Thursday Thoroughgood bury the defeated martial artist. A vanguard of Centipede’s army arrive on the scene. Thursday pulls some blades out of her afro and lets fly the soldiers something to worry about. She and Lei Kung then make a hasty horseback bolt out of what looks like some nicely stylized Wudang Mountain scenery. On the very next page, the horses are tied up outside a skyscraper crowded city skyline, with Lei Kung and Thursday making their way into a seedy, modern entertainment district.

Infinite Kung Fu weaves its ant trail plot through a nest of ideas, many of which are introduced quickly and many of which are stepped through just as quickly. There's a bit of Afro Samurai in what it's doing in that it's an eye drawing interweaving of native and non-native genre wolf-whistles. The significant difference is that while Afro Samurai, especially the manga, was driven by showcasing design, Infinite Kung Fu is more concerned with stringing together episodic scenes. It'll rapidly advance from a kung fu-movie-familiar bit of agitation between rival martial artists sitting across from each other at a teahouse table, to a bit where one army enacts the tableaux of crossing a perilous rope bridge, while an impressively kinetic scene plays out below as a second army fights off bands of zombies in the river's rapids; that parallel action resolves itself as the first army races towards a burning city an into a Romero-esque urban zombie riot.

Attitude and style serve as the glue coherencing Infinite Kung Fu as it goes from one scene where Lei Kung is wearing Qing era attire to the next where he's in a suit.

In regards to the latter, Kagan McLeod is a talented illustrator. He has a great pen for making the the page evoke what he's referencing, not easy in trying to capture kung fu combat, full of rapidly moving, twisting limbs, and, at the same time, projecting a look that is specifically his own. Flipping through and hitting any page, it's always this boldly movie referencing kung-fu/zombie/exploitation comic, and it's always boldly, immediately recognizably, Kagan McLeod's kung-fu/zombie/exploitation comic.

In the former aspect, think of the action movie case at a non-chain, Clerks style video store... a particularly progressive one because a lot of those shops weren't going to carry 36th Chamber or Master of the Flying Guillotine or 8 Diagram Pole Fighter. As the comic plots its trek from the scenes of one VHS tape to its neighbor, there's a real at the feet of the guru feeling to the journey. It's like an enthusiastic advocate offering up a stack of recommendations, all of which turn out to be excellent. For the newcomer, there's the excitement of a new domain to explore, and for the already familiar, there’s the ambition and verve to appreciate.

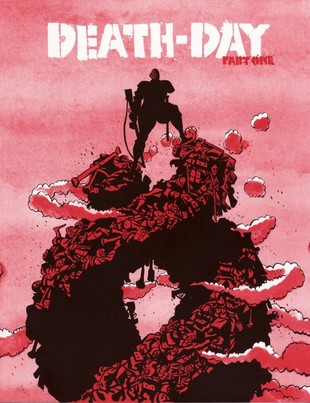

Graphic Novel Spotlight: Death-Day

Part One

By Samuel Hiti

online sample

You can look at Star Wars and start listing out the genres and specifics stories that it was inspired by... Kurosawa movies, and Dune, and heroic traditions, and yet, you have to call Star Wars "inspired" in the sense of being creative in its own right. The same sort of break down holds for Death Day.

It launches with a Kirby-tech army locked in an Aeon Flux-like battle slaughter Locraftian horde titans. Squads of circuit coated commandos creep through Nausicaa style labyrinths of fungal growths, trying to desperately avoid detection by six limbed gargantuas. Having spotted a towering helix structure, the human central computer Mother-0 books up and initiates battle. Mech walkers and columns of soldiers contend with the tearing limbs of the monsters. Meanwhile, similar chaos breaks out in the commanding war room.

Death Day resonates with a profound love and respect for the geek classics, and the brilliant enthusiasm that it casts on those works is certainly bound to bring giddy glee to a fan heart, but that's not the extent of the pleasure offered by the comic.

There's a lot to love about a group of stories that establish a mythology, whether that's the Marvel Universe or the Cthulhu Cycle or X-Files, but, at the same time, there's a cost to continuity. You lose the wild freedom of an unmapped landscape. You only get to put a Cthulhu or Dormammu onto the landscape once, then the next guy working the shared universe has to write around him. Even in the case of the work of a single author, established parameters are liable to paint a creator into a corner. Many of the current generation of top shonen manga artists credit early Dragon Ball as their chief inspiration. What earned that series the love of further hit makers was the fantastic possibility of the Monkey King of the Journey to the West beating up dinosaurs one week, Frankenstein the next, followed by kung fu assassins, and cowboys and Indians. Eventually, it was locked into the repeating pattern, which, like his later emulators, Akira Toriyama occasionally thrashed to try and shake off with time skips and the like.

Death Day's Samuel Hiti isn't writing a weekly or a monthly, so maybe it's not an entirely fair comparison, but what's remarkable about Death Day is its avoidance of the convention in its head first leap off the track. As reminiscent as it is, you can only wonder what's coming down the pike.

As "let's you and him fight" cool as Kirby versus Cthulhu stands in the vein of Freddy vs Jason, Alien versus Predator, Frankenstein vs the Wolfman, more than defining itself by the hallmarks of the geek canon, Death Day revels with the sense of sometimes exhilarating, sometimes terrifying possibility that raised those influential works. Samuel Hiti is taking full advantage of the fact that he's working in a medium that is only limited by the skill and imagination of the artist. The landscape of rock outcropping and grotesque alien growths, the armies of mecha and beasties bearing down of each other, the comic is full of images that are literally awesome. What elevates Death Day is that it's not just ideas and notations. Samuel Hiti has the ability to render these staggering ideas as staggering images on the page.

Tumblr blogs might have robbed "fuck, yeah!" of its potency, but Death Day's fungal avalanches and war room melees are what the expression was invented for. Comics can tell any sort of story. I believe that there's no reason not to use the medium to write a memories or a tennis romance, but at the same time, I believe that there's no better medium for imaginative spectacles. Unlike film or animation or video games, it's not dependant on teams and production committees. One person can create something truly amazing. With Death Day, it's thrilling to see something fantastic grow out of that niche in the media ecosystem.

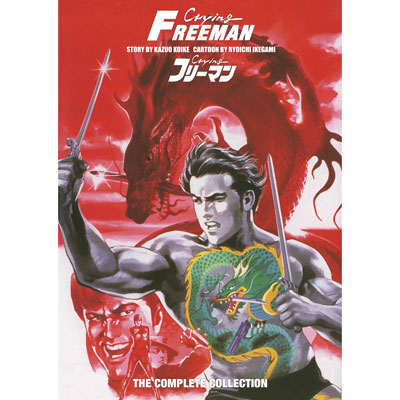

Anime Spotlight: Crying Freeman

Released by Discotek Media

Crying Freeman's tale of a Japanese artist, brainwashed into becoming the top assassin for a Chinese crime syndicate spring boards off 80's action extravagance. Before the age of Bay movies, only a medium like anime or manga could blow up violent spectacle this big. Maybe a Hollywood blockbuster can now keep pace with the scope, but as low brow as Transformers may be, you're not going to find it throwing taste to the wind the way this adventure will. A chief selling point of manga and anime to North American audience is, or at least was, that they present material not found in other media. Along those lines It isn't every day that you find a character whose origin involves being tied to a statue in a sexual embrace while being hypnotized via acupunctural needles. In a Kazuo Koike pot boiler serial like Crying Freeman, it's a brand of sex, violence and sexual violence that's exotic in any context.

For plenty of reasons, tech high among them, Japanese media consumptions habits have changed since America developed notions of them, informed by sources like Schodt's Manga! Manga! That said, though not to the extent that it once was, but you can still find manga readers from across a spectrum of Japanese demographics. There's still all sorts of niche manga and publications for the type of readers who typically wouldn't be found reading comics in America, not to mention circulation figures that put American comic sales to shame.

The same can't to be said of anime, the vast majority of which is made for and consumed by kids and geeks. When you get something that tries to reach beyond that, whither it’s a spectacle like Redline or programming meant to appeal to non-traditional anime watchers like Noitanima, the response is often scarily scant.

This non-overlap in audience is why anime adaptations of popular seinen (mature male audience) manga that aren't cute girl driven otaku-fodder are as uncommon as they are. When the rare series like the 2008 Blade of the Immortal or, again 2008, Golgo 13 are produced, they're rare surprises. Kazuo Koike is an influential legend of manga, and you've heard of the live action adaptations of his work such as Lone Wolf and Cub, Lady Snowblood, but unless you're an older fan of anime oddities like Hanappe Bazooka and Madbull 34, you haven't hit anime based on his work.

While times were good, anime could afford to try to ignore this trend. In Japan's boom years, money was being invested into anime, and money allowed consumers to buy expensive, single episode VHS tapes. Direct to video OVAs are still being produced, but mostly to be packaged with limited editions of geek-popular manga. The six episode Crying Freeman was released between 1988 and 1994, back when the Japanese economy supported production of anime based on a manga written to provide escapism for gainfully employed business men, who generally don't watch a much anime.

The high concept of Crying Freeman is that a young Japanese artist, whose medium is pottery, is of the brink on international acclaim when he lands himself in the wrong place at the wrong time. He's kidnapped, hypnotized and trained by a Chinese crime syndicate tied to the 108 Stars. Killing is anathema to the sensitive soul, so after completing his missions, following a ritual of wrapping the murder weapon in plastic explosives and detonating it, he silently shed's tears.

In the series' present day, during one of his hits, he's spotted by a Japanese woman while she's painting a park scene. She's 30 years old, a virgin due to her now dead father's fearsome political reputation, and hopes the handsome killer will sleep with her before returning to silence her. Realizing that she's the key to finding the chief assassin of the Chinese mafia, the police and yakuza soon begin working through her to plan their own counter attack.

The thing is, the whole weeping assassin quandary is quickly torpedoed in favor of casting the guy as the super-syndicate supreme commander. Maybe false advertising, but reasonable considering that Crying Freeman's raison d'être is to offer escapist, exotic adventures for men whose lives are anything but. Towards that end, it goes for the uber-competent, consummate professional... where the professional routine includes submarine-top knife fights... not to mention inflated honor that involves engineering rape-scenarios to test the Mrs' willingness to die rather than become a liability.

If you ask Kazuo Koike or his protégés like Rumiko Takahashi, the secret to the success of manga, and by proxy its anime adaptation is memorable characters. Well, I guess you could call the obese, low IQ, sometimes nude woman in the series memorable, but Crying Freeman's characters are far from the main attraction. I mean, the manga itself doesn't remain interested in what makes the lead a crying freeman, opting to use him as more a cipher for businessmen to project onto than a particularly outstanding character. Beyond that, the attraction of his adventures is its plunge off the deep end. It starts with serious reality. There's the look of the Ryoichi Ikegami manga illustration, which projects a minimally stylized reflection of reality that calls to be taken seriously. Then, there's Koike's interest in details and process. He's a Mamet for the inside how-to. As in his historical works, Lone Wolf and Cub, Samurai Assassin, and Lady Snowblood, he loves exploring and depicting how things are done. Then, inevitably, always, Koike takes it someplace weird: a board room of syndicate elders, one after another putting their bodies in front of a gunman to serve as human shields, or rhino killing, chakram throwing African revolutionaries.

Ultimately, there isn't much in the way of good sense or good taste in these adventures. At the same time, it doesn't seem like Koike is intentionally trying to be trangressive or offensive with Crying Freeman's interracial disguises and pervasive exoticism. It's more of a lack of respect for boundaries. Not everyone will love Crying Freeman. In fact, many will probably hate it, but its willingness to hold a straight face while running rampant is truly remarkable. When North America got Ninja Scroll and a string of other violent anime movies and OVA, we thought that this sort of excessive, rumpus was the norm. Really. not so much. So if you want a fix of that sort of blitzed business, you really need to look back to something like Crying Freeman.

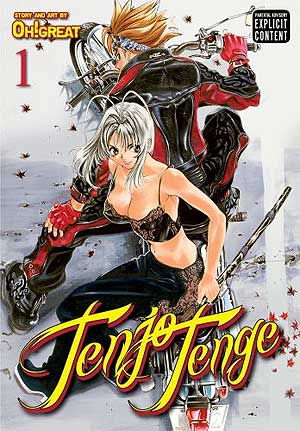

Manga Spotlight: Tenjo Tenge

Volume 1

By Oh!great

Released by Viz Media

Though not an easy proposition, I think that non-kids/teen fight manga could elbow out space for an audience in North America. I'd contend that more MMA based manga is more likely, whether moe gonzo-over the top like Grappler Baki or Tough (both of which were released in North America, maybe a bit too early to catch the attention of MMA's growing fanbase) or more realistic, sports structured like Hiroki Endo's (Eden: It's an Endless World) All Rounder Meguru or Teppuu. Still, even if Tenjo Tenge is for the most part, just a conventional fight series with some style and a propensity to flash its chest, it's still nice to see the mature audience fight manga niche filled out a bit.

Back in 2005, CMX punched a nice little impression in the history of manga in North America when reworked Tengo Tenjo for a release with its nudity, cleavage and rape covered up. To do it, they had to move logos on cover illustration to obscure chests, draw towels and undergarments and excise most of some chapters.

This wasn't putting a dress on the Venus de Milo. It was screwing with a trashy manga. That's not an affront to my affection for manga. It is however an affront to my sense of what constitutes a good idea.

I try to take a practical position on the subject of editing manga content for North American release. Given how violent the manga is, taking out some of the animal cruelty in Jojo's Bizarre Adventure is a bit irksome, but it doesn't invalidate the manga's release. The decision to change the shape of the object to which Fullmetal Alchemist's Greed is bound is such that the guy's no longer being crucified is pretty understandable.

I generally understand the dictates of business, but there are cases where I have little sympathy for the publisher suffering fan ire. Say a company (Dark Horse) takes a mecha series (Cannon God Exaxxion) from an older audience anthology (Afternoon) that carries known harshly violent works (Blade of the Immortal) and plans to release the series for a teen audience; if that series goes someplace inappropriate, I think they should have realized ahead of time that there was a great risk of that happening and not have to rethink how to handle the manga.

I have even less sympathy for the Tenjo Tenge episode. Few decisions have been as bewildering as the one by DC's now defunct, but then young CMX's move to rework Tenjo Tenge. First, it agitated a constituency predisposed to getting upset about real or perceived deviations from the Japanese original. The label never shook the negative impression made by the move. That they stepped into the predictable pit-fall is bad enough, but the motivation behind going through the trouble is a real head scratcher. What they did was take an R rated movie, and produce a TV edit.

Tenjo Tenge runs in Ultra Jump. Say you're a reader of Shonen Jump, the home of action manga titans like Naruto, One Piece, Bleach and Dragon Ball. Say you love that type of story, but feel you've gotten a bit old for Shonen Jump's stories of friendship and loyalty. Then you turn to Ultra Jump, home of the recent Jojo's Bizarre Adventure iterations (Steel Ball Run, Jojolion) Bastard!!, before it left, Battle Angel Alita: Last Order, Needless and the like.

So, CMX went to the home of fight manga with extra bits of nudity, violence and stuff American's would judge inappropriate for teens, and selected one of the particularly chesty, risqué examples, and tried to carve a teen appropriate fight manga. There are so many teen fight manga out there... it's like pulping a tree when you can write on back the junk mail envelope. Oh, and the author of the manga in question is also known for his porn manga work.

So, six years later Viz is rectifying the situation. You can now get a 3-in-1 sized collection of the manga, unedited for $18.

Ito Ogure, aka Oh! great, doesn't realy shoot for a novel pitch for his launch of Tengo Tenge. At least initially, it's just fighting for the sake of fighting. Brawlers Choichiro Nagi and Bob Makihara dojo challenge the fighters of Toudou Academy. In the lunch room, this plan comes to crashing a halt when the non-descript Masataka Takayanagi of the Juken Club puts Nagi through a wall. Still, it manages to earn Bob and Nagi both respect and enmity. The former comes from the Aya sisters. The elder, Maya, is a serious girl who never the less uses her mastery of ki to adopt the form of a chibi young girl. She decides to bring the pair into the Juken Club and train them. Meanwhile, the younger, more fanciful Aya, decides that she's destined to marry Nagi. The enmity comes from the school's Executive Council, who sends their enforcers to punish Bob and Nagi. In that the manga makes its impression.

There's plenty of cleavage from the get go. Nagi runs into a showering Aya, yielding a double page spread of Aya's naked bust. The next page is dominated by Aya's breasts; just her breasts; no other anatomy. Then, when the Executive Council enforcers join the fray Oh!great really lays out what he has in mind for a mature manga series. Emphasizing female nudity, he launches into an extensive rape scene.

I'm too desensitized to get too morally outraged about this. It's no Master of Martial Hearts making me see red.

As I've said before, I'll forgive anime or manga plenty if it offers good fight scenes. Except, I generally don't have to follow through on that, because the anime/manga with fight scenes that really impressed me rarely turn out to be otherwise meritless.

I first caught TenTen probably about a decade ago, and I remember being a lot more impressed by it back then. I don't think that my current, diminished impression is a function of my tastes shifting or of seeing more manga surpass what it does. Instead, I think it speaks to Oh!great's strengths and deficiencies.

Oh!great's fight choreography isn't anything special. Manga artists who are skilled at conveying fight choreography think in terms of sequential exchanges. These aren't absent, but that's not here Oh!great's head is at. He's more about the big panel or full page or multi page spread money shot... the supplex planting a guy's head into the concrete... the giant panel of a boot to the head; there are plenty of those... the crouching woman, about to let loose a flight of throwing knives. It's the illustration and not the scenes that displays Oh!great's greatness. Design and posture and battle damaged scenery all complement each other to make a statement. I remember being revved up by tableaus of Bob swings his legs at his foes, Nagi ready to launch himself into battle and Aya flinging toughs into the wall.

That's the problem. I remember it. Tenjo Tenge loses its magic on a second viewing. Oh!great is planting all these flag pole moments and not stringing much of anything between them. It's all big moments without much of a cumulative effect. Whether its the rape scene or the character background, three volumes in, he hasn't established anything really counting for the players. And, at the same time, battles are so big effect focused that the dynamic exchanges aren't interesting. I suspect if I were just seeing Tenjo Tenge for the first time now, the look would still ring my fight fan bell, but that effect based approach has a real "seen it “diminishing return.

AICN Anime on Tumblr