Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Anime Spotlight: Project A-ko

Released by Discotek Media

There are anime fans, then, there are fans of anime. The former are fans to the extent that they identify themselves as such. They get excited, maybe very excited, about the latest hot things. There's nothing necessarily wrong with that. After all, anime's a very pop medium. Then, there are fans of anime, who are genuinely curious about the form.

Many anime fans aren't going to care for Project A-ko, but 25 years after its creation, Project A-ko is a special artifact that's a must own for fans of anime, and, it's a real boon to enthusiasts that, following the closure of Central Park Media, Discotek has picked the feature up for a new release.

With creative freedom and a total absence of pretension, Project A-ko is a shaggy dog action comedy thrown together by geeks, about super powered school girls, mecha, aliens and not being late for school. The factors that make it brilliant and pleasurable also make it paper thin even by the standards of a generally under plotted genre. In other words, in terms of what's being animated, Project A-ko is a glorious mess.

Project A-ko opens with a slow, absolutely gorgeous, immaculately animated space docking sequence from Shouichi Masuo - later animator of the climax to Evangelion's classic synchronized battle. The connection between this beautiful bit of animation and the plot is gossamer thin. Later, there's a fantastic homage roadster to robot transformation sequence, full of bits moving in and out of place. This ends up with a shot of the interior, in which the pilot is entirely discombobulated in a space overcrowded by mech parts and further ornamented by a spinning globe and one of those clanking bamboo deer chasers. The sequence is a metaphor for the feature... a marvel, a pleasure to watch, but not really particularly funny.

Project A-ko's set up was novel to North American audiences when sailor suited school girls were. Not so much now. Athletic to a super powered extent (a gag shows her to be the daughter of Superman and Wonder Woman) A-Ko and her cute, but entirely inept childhood friend C-ko transfer to Graviton High school, where they're confronted by the brainy rich girl B-ko, who falls for C-ko and declares enmity on A-ko. So, every day, B-ko outfits her minions with mecha and lies in wait for A-ko at their school's gate, initiating another in an escalating series of duels. At the same time, a group of aliens begin spying on the girls with designs on invading Earth to capture one.

As a comedy, Project A-ko has all sorts of problems. Extravagant movement, striking juxtaposing and reference gags are employed in ways similar to how they would later be in spastic 90's comedies like the works of Shinichi "Nabeshin" Watanabe. It's what a bunch of geeky animators think is funny, and then it's strung together without much of a plan. It's not particularly unlikely that a modern watcher will get the gag about the schoolgirl who towers, fights and screams like Fist of the North Star's Kenshiro, and that particular image is apt to be mildly amusing regardless. Alternatively, it's a small minority of American anime watchers that are going to get the Harmageddon spoof, and that one is apt to be just bewilderingly absurd without the recognition that the scene is in fact a parody.

More generally, there are animators who have a gift for comedy. These ones largely don't. Premises are stupid. They're haphazardly scripted. The creators didn't even let each other know what gags they were building to. Ultimately, what's impressive about those gags is seldom the jokes themselves.

More significant than the success or lack thereof of the anime’s comedy, Project A-ko is the product of a special moment in anime. The micro circumstances had to do with Mamoru Oshii leaving the popular anime adaptation of Rumiko Takahashi's (Inu Yasha, Ranma 1/2) Urusei Yatsura. The Ghost in the Shell movie director is now known for his serious material, often characterized by conversation and stillness, but he found success with a often physical, visual gag based comedy concerning the relationship between a lecherous teen, and a tiger striped bikini wearing alien girl. Along the lines of his basset hound mascot, it's easy to get the notion of a dour, humorless Oshii, not helped by the very particular nature of his relatively recent instances of relatively lighter work, like Fast Food Grifters, but, back in the 80's he helmed a genuinely funny, manic hit comedy.

After 106 episodes, parlaying the Urusei Yatsura TV into a pair of movies, the second of which fused Urusei Yatsura's brand of humor with Oshii's interests in cognition and the nature of reality, Oshii left Urusei Yatsura, after which Kazuo Yamazaki would oversee the series for another 89 episodes.

Thrown by Oshii's departure, Urusei Yatsura staffers like animation directors Yuji Moriyama and Katsuhiko Nishijima began trying to put together a new project that would recapture the dynamic work of Urusei Yatsura.

In terms of macro circumstances, you can argue the artistic standing of anime in the mid 80's, but, factoring the money invested into the industry and freedom that came with that money, the period in which Project A-ko was developed was a high point. After leaving Urusei Yatsura, Oshii was able to make the often abstract, Bible symbolism laden Angel's Egg and a bit later, Patlabor, a mecha anime with more politics and humor than what traditionally drew audiences to mecha anime. Artists who'd later drift off into other fields (manga, video games) were excited by the opportunity. Veterans had no problem finding employment, creating the openings for young, talented creators to prove themselves on a project like A-ko. Plus, there were the resources to really animate the hell out of an A-ko. In this case, artists didn't have to worry about cel counts, allowing them to put together both extravagant action scenes and small, pay-attention-to-catch background gags.

I'm less convinced that Project A-ko flourished because of it, but the production was also influenced by a notable lack of legal impediment. It was able to use the Pokémon seizure effect, but, more to the point, it was able to lift freely and directly with impunity. Mecha and character designs were transposed wholesale. On one half, watching these fit in the hyperkinetic scheme of Project A-ko looks impressive more than ease. On the other, even when the references are recognized, if the animation is anything but lazy, the comedy has a tendency to be.

There was a recent convention panel on remarkable full motion animation in anime. Late in the talk, it makes the point that the importance of story to anime's appeal should not be underplayed: Project A-ko being the perfect example of a beautifully animated work with little story to speak of... largely animation for the sake of animation. However, that's not to say that there isn't plenty to appreciate about anime that simply looks amazing. A lot of the anime that we see is defined by its limited motion. The majority of anime is produced for television, and from its inception with Osamu Tezuka's Astro Boy, televised anime is built around small budgets and animating around the consequential limitations. Anime with the attention to animation and the freedom afforded to Project A-ko are rare, so, even if the story is bogus, A-ko presents special landmark in anime.

Anime Spotlight: Durarara!!

Part Three

Released by Aniplex

During a FanimeCon convention panel, Aniplex announced that the Durarara!! anime will be airing on Cartoon Network's Adult Swim block starting in June.

The anime is the second time director Takahiro Omori, writer Noboru Takagi and studio Brains Base tackled a Ryohgo Narita light novel. Like previous adaptation, Baccano!, the Durarara!! opening does an on-screen name splash Guy Ritchie style cast introduction, identifying 15 significant characters. There are more reoccurring ones and later introductions too. This includes runaways, a pharmaceutical executive, an underground surgeon, insanely violent muscle for a debt collector dressed like a formal bartender, otaku with a taste for manga-inspired torture, an information broker, who, according to Wikipedia, is named for the Hebrew profit Isiah, an Afro-Russian sushi chef, and, a headless horeswoman whose horse has become a black motorcycle, clad in black herself, except for a yellow helmet with cutesy ears.

However, set in Tokyo's Ikebukuro entertainment district , dealing with some remarkably empowered otaku and drawing from Haruhi Suzumiya-esque ideas about what constitutes interesting experiences, globally, Durarara!! has a more devoted following among devoted anime fans than the American set Baccano.

While Durarara!! offers plenty to recommend, this final third is problematic. Explaining how is going to require some vague spoilers.

The anime adapts the first three of what's currently nine light novels. So, its terraced mysteries have a top tier which doesn't represent a cap to the whole affair.

Like the other mysteries that set the stage for this anime-finale, the clues are there, especially evident on a subsequent viewing. I've said in previous reviews, that Durarara!! sets itself in bustling city district, defined by its comings and goings, and yet its story is something of a closed system. As before, while others might serve as active agents, the catalysts are those individuals named in the opening. Outsiders are particularly instrumental in this last situations, and as such, the particular is less than ideal, but even then it's still better than bad.

Always mindful of its philosophical underpinnings, the problem is not that this last segment of the anime is thoughtless. Characters have some solid world view conversations. The climax has a nice key into some of the earlier discussions. And, again, especially in retrospect, it's a valid expression of the themes that the Durarara!! developed all along.

It's not even the extent to which it does or doesn't deliver on the promise of a ragnarokalictic battle on the streets of Tokyo that lands Durara!!'s conclusion in trouble.

The problem is that the way that it casts its key characters in a bad light spoils the fun. Like the hit Haruhi Suzumiya, one of its most potent ingredients, especially among its otaku/geek fan base, is the notion of camaraderie with interesting people, doing interesting things. In particular, the axial hero Mikado Ryugamine leaves his rural home prefecture to find a more dynamic life, and along with a pair of other regular-ish teens, he gets to rub shoulders with colorful street legends, like headless horsewoman, an underground surgeon, and yeah, the decidedly otaku, tough. Despite the danger from the environment and from each other, they're in together as their own, weird crowd. And, both the normal and the exotic are bound together in the act of reinventing selves. It's no wonder that Durarara!! is a hit among anime fans. It's not just that there are some fearsome geeks in the mix. As the characters parade into the open to recreate themselves, the city that is so central to the anime almost functions like an anime con.

This last stretch still functions that way. Unfortunately, the principal principals get chumped. Their actions, by commission and omission drop them into the trap set for them. Consequence is fine. Mikado Ryugamine's sharp thinking, especially under pressure looked like his entre to the world of the weird and dangerous, but some difficulty could have served to underscore what was special there. Frustration is fine. Action anime is often a hydraulic exercise. It relies on the pressure. The problem is that the leads fumble into the finish line in a way that doesn't vent that pressure and as such makes the struggle to get there that much unsatisfactory. Neither tragic nor triumphant, the heroes close down what is to date their only anime venture with a C grade. It's not so much redemption that they need as it is getting their acts together. "Needs work" is not for the ideal final comment on the characters who you identifying with in what was an empowering adventure.

Durarara!! is highly affection-inspiring anime. It nails the aim of letting the viewer feel included in the action of a cast of colorful characters. That's why it's a mess that its paramount point of view characters fail to rise to the ultimate occasion. How badly this ending fails to work is a sign of how well the anime does work at its best, and, it's telling that the flub inspired the desire for more material in hopes that it might return to form.

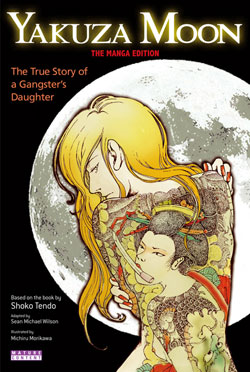

Manga Spotlight: Yakuza Moon: The True Story of a Gangster's Daughter

By Shoko Tendo and Sean Michael Wilson

Illustration by Michiru Morikawa

Released by Kodansha USA

Shoko Tendo's memoir Yakuza Moon recounts her troubled life story, growing up the daughter of a yakuza boss. Starting in her childhood, in which adults took her family connections as a license to dehumanize her, through a home life frequently upended by drunken rage, naked infidelity, incarceration, illness and crushing financial debt, through her self abuse and abuse from the men in her life, and ultimate discovery of the confidence to reinvent herself as the person she wanted to be, it's an often harrowing, never glamorized account.

Kodansha International released a translation of the original, prose version in North America, and had plans to release Sean Michael Wilson (the manga adaptation of Hagakure: The Code of the Samurai) and International Manga and Anime Festival award winner Michiru Morikawa's graphic novel adaptation. Unfortunately, after almost five decades of offering English language resources about Japanese culture, Kodansha International, publisher of Frederik L. Schodt's seminal manga manga, and more recently The Otaku Encyclopedia, Yokai Attack and Ninja Attack shut down in April. However, the newly launched Kodansha USA label materialized and picked up the release of the worthy Yakuza Moon adaptation.

Shoko Tendo is not badly served by the translation to manga. Morikawa effectively conveys the human element. The emotions and when appropriate, the vulnerability of the subject is always unmistakable in the visual depictions. I imagine that every scene successfully projects the original author's intended sentiments. There are panels and sequences of panels in which the body language is stinted or odd enough to distract, but those are uncommon enough that the instances stand out.

Not a problem so much as a "what if?" I wonder how the narrative would have been served by a more distinctive look. There's a bit of the generic here where the story breathes through the specific. Shoko Tendo is not inclined to spare the details. even, or maybe especially, when they're uncomfortable. And, it's not that Morikawa is lazy by any stretch of the imagination. Her cover effectively recreates the striking original image of Shoko Tendo's tattoo, and if you look through the book, it's evident that it's all thoughtful, with smart attention to matters such as attire. But, if you again look through the book, it's also only as distinctive as the events of the particular page. Along the lines of the weirdly generic appendices about scripting and drawing manga or comics (comments about the difficulty of lettering sit uneasily on the tail end of this story), events that are specific "Yakuza Moon" are surrounded by images that, out of context, just look "manga." It tells the story rather than taking an active part in establishing its reality. Maybe that avoids a conflict between the art and the story, but I couldn't help wanting some more grain on the surface.

Having not read the memoir, I can't comment on how condensed the graphic novel is, but given all the misfortune brought upon by circumstances and her own behavior, it doesn't seem like manga's jagged journey misrepresents her story. It's one knock after the next, with the times in which affairs are righted or kindness is displayed occurring as rare shining moments. So, it's so fraught that if it weren't real, it'd be too much. Because it is true, it is truly effecting.

Yakuza Moon becomes the story of Shoko Tendo reaching the point where she has the strength to free herself from the turbulence of the legacy of her father's yakuza life and her own wild days. Having only read the manga, I'm not sure where some of the hitches in the account of this transition were introduced, and specifically whether it's a function of the manga's condensation of the narrative.

On one hand, eventful elements translate meaningfully. For example, when tattoos take on a personal significance in her life, we see the impetus and read her explain what she discovers and that resonates. On the other hand, the manga offers late introduction of dreams that she had and qualities she's told she possessed. Especially as they relate to her early childhood, it's true that there were more pressing concerns to convey in the pages to work with. However, because we weren't aware of it in the first place, the reaction is more along the lines the "why wasn't this previously shared" than appreciating how she's recaptured a lost quality or affirmed a strength she forgot she had.

It's impossible to have a cold response to Shoko Tendo's story. More than the emotional response of being moved by it, it warrants being engage, with some effort to understand her life. And with that there are some difficulties, partially as a function of the transition to manga, partially as a function of the original material.

Shoko Tendo's motivations and decisions are anything but mysteries. Some of the most common descriptions of her memoire are "blunt" and "matter of fact." The manga inherits that. Nor is any element of her story incredible. It still inspires consideration of why she made the decisions she made. And, "why" still crops up, with gaps seeming to emerge. After a troubled and troubling string of relationships with men, working as a hostess in a club frequented by yakuza, she hooks up with a man ten years her senior. He introduces the notion of marrying her, and then "someone told me the unthinkable - he was married! The news hit me like a ton of bricks." That the man might be married should be entirely unthinkable seems like IT should be unthinkable. She knew that it was a danger of the crowd. She'd been personally burned by that. Again, it's not incredible that she be fooled, but it is curious. Maybe the original prose fleshed out her thinking, maybe it didn't but, inspired to apply some psychological order to the chaos of her life, the episode inspires the wish for more insight available into matters such as how she managed fooled herself.

The complaint stemming from the original material is a complaint about what Yakuza Moon is not, what it never aimed to be, and what it didn't need to be, but which will still matter to many readers. Yakuza Moon is not a general examination of yakuza and their families. The only insider talk is of the life's consequences. It's the story of Shoko Tendo, and that's important and meaningful in its own right. As such, it's concerned with the meaning of events to its subject, with little exploration of the functioning of yakuza life. Even accepting it as a personal account and not a tell all, even having some foundation of knowledge on the subject, the book still feels like it could benefit from more context. While I haven’t read exhaustively on this subject, I'm far from ignorant. Still, when talk becomes laden with reference to employment at hostess clubs and aims of working towards being the "number one," the absence of any explanation of the system is felt. I imagine that if Yakuza Moon is a first exposure to the elements of Japanese society without obvious American analogues, though book isn't going to be bewildering, the want of background information is likely to be more pronounced. Since it likely wasn't in the original, the adaptation would have benefited from some expository end notes far better than it does the appendices in which Wilson and Morikawa explain their process for creating comics.

Yakuza Moon is Shoko Tendo's story and not an impersonal look at yakuza life. It's without a doubt a memoir and not an expose. It's constructed to relate a story of specific pain and self discovery. Factor in the matter of fact approach to convey the personal history, and its narrow focus becomes that much sharper. This adaptation takes it one step further. By no means inappropriately unreal, the illustration style of the manga does shade towards the abstract. This look takes away even more of the world such that, even though there are other people who affect Tendo, it's a book that's alone with her, or, more specifically, her circumstances.

Most North American readers are likely to come to this with only a vague notion or spotty knowledge of yakuza, and what glamour might be there for that audience is flimsy enough not that it didn't require a razor quite this keen to slice away preconceptions.

There is an extent to which this directness comes at the cost of material that could be used to better understand Tendo, and because the book does capture the power of Tendo's story, it also does prompt a wish to have seen the culture or Shoko Tendo's thinking be a bit more fleshed out.

AICN Anime on Tumblr