Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

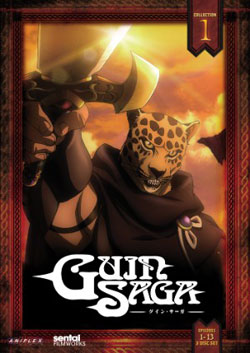

Anime Spotlight: Guin Saga

Collection 1

Released by Section 23

Even more than anime that appeals to my own, personal tastes, I appreciate anime that I can point to and proclaim “I know you don’t watch you much, if any, anime now, but watch this one!”

I wanted Guin Saga to be anime that I could recommend without qualification. Given how the novels were marked by often cinematic scale and boldness, and given how they helped inspired the still popular Berserk, I suspected that that sort of attention commanding appeal was within the realm of possibility. I hoped it would offer fantasy fans reason to watch some anime and anime fans a gateway to the novels.

I’ve called the Guin Saga novels fantasy for people who no longer have patience for fantasy novels. They were quick and sharp. You could read them in one sitting and though they never lost an opportunity to plot the portentous movements of fated characters, you could feel like something was put on the line. As in the teeth gritted bits of Berserk, there was a real desperate sentiment. The books published in North America culminate in the Battle of Nospherus, which would be comparable to Return of the Jedi's Battle of Endor, if rather than a crowd pleasing demonstration of Luddism and merchandising, the Ewoks were a species that had to put aside inter-tribal cannibalism and slave capture in order to wage an ecology razing insurgence on the invading empire... and if that antagonist force were comprised of conscripts, lead by people with some honor or at least sympathetic ambitions, set on their path by harsh realpolitik .

A few volumes into the 130 volume long Guin Saga, the fantasy epic committed itself to total war. It might only encompass tens of thousands of monkey-men versus an expeditionary force, but rather than skirmished based Risk tactics, the novel committed itself to unbridled, apocalyptic warfare

The Guin Saga anime disappointed my high hopes. It’s a dedicated example of a no-longer over represented genre in anime, and in that, I can say, if you are a fantasy fan looking for fantasy anime to watch, Guin delivers like few other recent works. With swelling (if a bit type-cast) music from Final Fantasy composer Nobuo Uematsu and crystal cities and haunted keeps from a squad of background artists ready to detail out ornate chambers and badland battlefields, Satelight evidently relished the chance to produce this sort of fantasy epic. Yet, its flaws and short comings are such that Guin Saga is something to watch, not something to excite. Consequently, I wouldn’t push the anime on the uninterested.

Fantasy has not been a dead genre in anime.

The teenage boy protagonist of Xam’d allows a strangely pale girl onto a monitored school bus in his militarized home state. The mystery passenger detonates a suicide bomb, killing and injuring many, but also infecting the boy with a stone that transforms him into an insectoid monster. Another mystery girl, this one decidedly inspired by Hayao Miyazaki's Nausicaa glides down and chips away as the boy’s hardened new form such that she’s able to trigger a shift back into a human body. This pair is then picked up by postal air ship as it flies between warring states.

I’d argue that Xam’d is a fantasy anime. It’s not a fantasy anime in the Tolkein/Dungeons and Dragons tradition. Nausicaa does invite Tolkien comparisons, but though Nausicaa informs Xam’d, those aspects don’t transition over.

Back when anime was supposed a medium that delivered thoughtful sci-fi or violent porn, depending on who you asked, it was easy to find fantasy anime, where "fantasy" was the swords and sorcery sort that leaps to the mind of most when hearing that term. In the wake of the OVA boom, but also a solid vein of what was making it to TV, anime went through a phase from the early 90’s through the mid part of the decade where action/adventures set in high fantasy or high fantasy inspired worlds were plentiful... and for a while, the medium was peppered with elves and fireballs. Anime for the last decade or so has been markedly out of love with fantasy as its traditionally associated. Now something like the story of sword wielding monster hunting women, Claymore is something of a novelty. Whether it's been a function of the evolution of video games or the ascent of moe, anime's largely looked elsewhere.

Guin Saga enthusiastically plucks the sword from the stone to raise it in the name of fantasy traditionalism.

The black knights of Mongual succeed in storming the crystal city of Paros, and, in a desperate move, the soon to be deposed royal family secret their twin children Rinda and Remus into a mysterious chamber. The pair find themselves in the haunted Rosewood, where the Black Count Vanon’s patrols are hard and or desperate enough to brave the forest’s flesh stripping ghouls to find the missing Jewels of Paros. By the apparent dictates of fate weaving god Janos, Remis and Rinda happen upon Guin, a stranger with the body of a perfect warrior, a permanently affixed life-like leopard mask, and a mind free of personal history except for the name "Guin" and the word "Aurra." As stunning as Guin’s brute force and preternatural fighting abilities prove to be, they aren’t enough to best the overwhelming odds. The group is captured and brought to Vanon’s dungeons, where they await his sadistic attentions, along with previously imprisoned monkey-girl Suni and survival minded mercenary Istavan Spellsword.

Guin Saga author Kaoru Kurimoto, along with Vampire Hunter D’s Hideyuki Kikuchi, are largely responsible for carving out the publishing niche for "light novels". Light novels are physically small books, printed smaller than an American paperback or a graphic novel, often illustrated, often collecting works serialized in a magazine, often read by school aged audiences.

Light novels typically pair rapid paced writing with development of a place and its spirit.

This sort of place can be very much of this world. The 36 volume Maria-sama ga Miteru (The Virgin Mary is Watching or Maria Watches Over Us), aka Marimite, about a girl in a prestigious Catholic school, is a relationship/character driven light novel series and a mainstay of the field. And, there are plenty of examples in which in place is more fantastic.

Set in the year 12,090 AD, after a nuclear holocaust nearly wiped out humanity back in 1999, and after a reign of vampire lords took hold, then began to decay over the centuries, Kikuchi's Vampire Hunter D related the nature of the Gothic/Western world, from his hero's cape/duster and robot horse, to the workings of half functioning technology, to the hinge that was no longer maintained. From the Swiftian societies visited during Kino's Journey to the demon lord cosmology of Slayers, anime has proven able to capitalize on the detailed backgrounds offered by light novels. In fact, some adaptations, such as Black Blood Brothers, seem to do little but introduce and explore those worlds.

Guin was the hero of 130 novels, five of which were released in North America by Vertical, before the life of his creator, Kaoru Kurimoto was cut short at age 56 in 2009. The figure able to stand in that ocean of world building and plot churning is a sort of Conan meets classic masked wrestler manga/anime Tiger Mask. Not Conan in the sense of the reductionist, grunting brute character that comprises the general notion of the character; Conan in the savy, destined to be king Howard sense of the character. At the same time, Guin is both more obviously animalistic and more enabled; a figure sent into the world by gods, maybe higher, maybe lower, to seize a place in history. He’s pulp informed, classically informed, and forcefully his own being. Giving further evidence of this sort of synthesis, Kaoru Kurimoto’s second most popular work, Makyou Yuugeki Tai, was the Chinese epic Water Margin meets Cthuhlu.

Veteran Kenyuu Horiuchi might not sound like the first choice for the role of Guin. He was Seinfield in the Japanese dub of Seinfield, Lister in Red Dwarf, Raiden in the Metal Gear Solid series, Sanson from the proto-Team Rocket Grandis Gang of Nadia: Secret of Blue Water. He has also been some implacable and capable, if not loomingly immense characters like karate-Jesus Toki in the recent Fist of the North Star projects, Angel in Buffy and Han Solo in the Special Edition release of Star Wars Still, Horiuchi makes for a sufficiently commanding, savagely regal figure, able to literally put his opponents into the ground with his fists. In his world introduction, he beats down a squad of armed knights with his bare fists, one of which hits a tree with enough force to leave a seared trench. Night falls and the defeated knights are animated by malevolent spirits. Guin grabs a sword and a torch and begins going at the undead, popping the first phantasm to dare come within his reach.

The anime Guin works. With smarts and cracking fists, he carves out justification too shed embarrassment in thrilling in the exploits of a figure who wouldn’t be out of place in an 80’s toy commercial cartoon. He’s a demigod dropped onto a conflict tensed landscape, both innately familiar with and alien to it. Even the amnesia doesn’t present a problem, since he’s both smartly engaged with the world and forcefully prepared to shape it. His dominance as he wades into the conflict as a combatant and as a general is magnetic. More so because is bound by some physical limitations. Put in the wrong spot, he’d disarmed and captured.

Though the Guin Saga anime is by no means stingy with its lead, he doesn’t loom large enough to support the adaptation on his shoulders.

Director Atsushi Wakabayashi's history as an animator comes through in the fluid pans and snap motion of the melees and single combat. It's those that succeed in establishing Guin as an animalisticall y fast, forceful presence. However, while they register as impressive, they aren't superlative action scenes. They lack creativity or a mind for choreography. The best example of this is an unarmed fight between Guin and a giant. It's a wrestling match, arguably a possible tribute to Tiger Mask, but not a pro-wrestling bout plotted out by someone who has thought about the sort of fighting that pro-wrestling is supposed to stylized. With some nice pans and fluid movements the combatant wind up straining against in each other in ways that don't really decide fights.

It doesn't look like the production really thought of how to best animate the action and it doesn't look like it thought its way around the other pitfalls of adapting the source either.

A sense that problems were Satelight makes it evident that the subject of Guin Saga is difficult to animate. This issue isn’t new to fantasy anime. The genre cornerstone Lodoss Wars had some remarkable gaffs in composition of castle shots, while its dragons were fantastically detailed creatures that basically just slid across the screen as near static forms. Guin Saga has trouble with its armies. The horses under mounted knights move unnaturally. There’s a lot of obvious short cuts via looped replication.

And, the series progression likewise makes it evident that Guin Saga was difficult material to adapt.

With its first book transpiring over little more than two days, the Guin Saga novels proceed with Zerg Rush pacing. This could cut a convoluted path, but rather than veer out of control with this momentum, Kurimoto enforces a coherent arrangement of events. The particular circumstances might be authorially driven chance... make that the dictates of fate weaving god Janos, but the flurry of situations set up and resolved makes each incident, as well as the novel itself, satisfying.

The prose incarnation maintains that dexterity going forward, but begins to juggle in many more objects.

The novels won a lot more vocal English language fans after the second was released. In part, because that second novel began demonstrating how much goes on in Guin's world. Remus and Rinda have their own brilliant or dark destinies. Istavan has his flaming future. The Mongaul are a patch on a political tapestry. Their field commander for that early battle again Guin, Lady Amnelis is a would be general, destined to be political chess piece.

Guin, Rinda and Remus’ misadventures with Black Count Vanon is an introduction, after which the group flees into a nearby wasteland. There, Guin begins to unite the tribes of monkey-like Sem to fend off the invaders. After a bit of Starship Trooper martial appeal as the villains grab their torches, build a pontoon bridge, and march into the wilderness, the richness of the Guin Saga novels begins paying dividends.

No one is going to mistake the Mongaul forces for "good guys."

Regimented, clad in monochromic armor, out numbering their poorly armed adversaries, they present the impression of the classic army of darkness. They recently blitzkrieged Remus and Rinda's kingdom. They're an organized, ambitious, martial society that values a brutal brand of pragmatism. They're in the midst of an expansionary adventure, in which they aim to exterminate the tribes of the Nospherus wilderness, build outposts on the land and claim a hidden WMD. At the same time, when Guin Saga gives them the narrative spotlight, they become sympathetic characters. The rank and file are conscripted young men, far from their farms or home cities, harried by cannibalistic Ewoks waging a scorched earth campaign, marching through an inhospitable wasteland. Their captains and generals are largely competent veterans, trying to do the best by their soldiers, and focused on achieving objectives rather than meta-schemes. The nobility commanding the mission are immature and unthinkingly entitled, but there's a sense that they are exceptional under conventional circumstances and not entirely with personal virtual. Bested by Guin at every turn, their plight invokes the kind of compassion that one might feel for Daffy Duck.

The anime doesn't figure out how to balance the depiction of the foes in such a way as to capture the tension established in the novels. The nastier elements concerning the Sem tribes don't make it in, not helped by the fact their design will have any child of the 80’s thinking Monchichis . The anime finds time for the Mongaul blunders since those establish significant characters but in a way that suggests stupidity rather than dangerous recklessness born of perceived necessity. Consequently, the two sides just seem to be boffing each other around. Without the desperation expressed in the novels, the Battle of Nospherus is just a series of dominos being knocked over; little more than plot progression.

Allowing Guin Saga to just tumble forward with its plot presents a particularly pronounced problem. Kaoru Kurimoto threads a tight needle with the stories use of fate. Characters and events are regularly moved by cosmic forces. It’s not just chance meetings and the protection of narrative necessity. Profound aid falls into Guin’s lap. He is explicitly aided by deus ex mechina. In the novels this is balanced by demonstrations of the superhuman exertion required of Guin to be an instrument of fate. Some of that is internal and couldn’t easily be translated into new medium. It’s hard to fault the anime for not over using monologs. But, some of those moments that establish that fate isn’t enough in and of itself are external. To the astonishment of his companions, Guin grabs bits of armor and wades through a sea of flesh-eating ooze. In the anime, he winds up with a suit of full black plate at a point where he needs a visible transition. The anime tries to make the flesh-eating ooze horrifying, but it doesn’t use it to make Guin a figure whose tendency is as essential as his fate.

Despite scripting some of the Death Note and Berserk anime, there’s little reason to have a huge amount of faith in Guin Saga series composer Shoji Yonemura - he wrote the Ninja Scroll tv series and ambitious mess Glass Fleet. Director Atsushi Wakabayashi seems better suited to thinking about how to visually handle particular movements than tell the story. The results are some nice backgrounds, some impressive punches and spectral visions, and large gaps in conveying the strengths with which the novels connected to their audience. There is a far better anime in Guin Saga. It is not a failure in that it’s meritless or entirely unentertaining. It is a considerable disappointment in that it is probably the one and only chance to adapt Guin Saga and ends up filling a niche left open by a dearth of traditional fantasy anime rather than a reason to be enthusiastic.

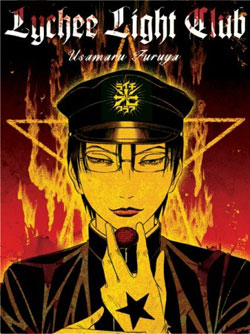

Manga Spotlight: Lychee Light Club

By Usamaru Furuya

Released by Vertical

Preview Online

If I didn’t shave my head, what could cause me to pull out my hair would be that something that would command all sorts of attention in any other medium is sure to be ignored in manga. (Unless it's Death Note) There’s a series called Saint Young Men, a comedy about Jesus and Buddha living as modern apartment-mates. It’s not licensed in North America, an absence accompanied by mummers of the outrage it would invite. I think that notion is bunk. A) English language comics like Battle Pope and Chosen have escaped the Inquisition. B) The cases of manga winding up on some inopportune library shelf are far outnumbered by the manga that received little notice outside the sphere of people who notice manga.

Takashi Miike remains an object of fascination in North America, built on Ichi's the Killer's tempura torture and paint the wall red knife edge kicks. Not sure how many Eastern European movies you've heard of, but thanks to controversy and mutters of what it includes, if you've heard of any, Serbian Film is apt to be one. But, unlike film, manga can be as shocking, trangressive and graphic as it wants and it'll largely escape notice, even by audiences looking for those qualities.

How's this for a pitch? Imagine He-Man Women Haters Club fell out of a time capsule as 13 year olds, fellated each other and built a girl abducting robot.

Under the guidance of manipulative, paranoid chess player Zera, a group of a group of anachronistically dressed students convene their secret childhood organization, dubbed the Light Club from a conflation of their name, and engage their plot to contend with the onslaught of adolescence. They create a being they dub "Lychee", and program it to bring back girls to their abandoned factory lair. With drug coated kitty masks, Lychee begins kidnapping a series of women and girls who unsettle the disturbed group for one reason or another, mainly that they're repulsed by adulthood in general and panicked by the sexually developed female body in particular. Finally, Lychee grabs the idealized Kanon. This all happens in the opening chapters, after which, while the saintly Kanon begins elevating Lychee towards humanity, fear and betrayal begin metastasizing in of the Light Club.

Lychee Light Club ran in Manga Erotics F, which, despite its name, its not an erotic manga anthology, or, by in large, what Secret Comics Japan referred to as "useful." It's a particular publication, even among what Erica Friedman recently referred to as “fifth column” magazines. This isn't as alt/alternative as Garo (where Furuya's debut work, absurdist gag series Palepoli, sampled in Secret Comic Japan, ran) or Garo's descendant Ax. Nor is Manga Erotics F as close to the mainstream as Jump SQ, home of Furuya's teen art/psychological interpretation series Genkaku Picasso (released in North America by Viz). Nor is it marked by the reliably male appeal of something like Young Sunday (home of Inio Asano's Solanin, but also Hideo Yamamoto manga like Ichi the Killer - also Furuya's post Palepoli gag manga Short Cuts - serialized in Viz's Pulp anthology)

Manga Erotics F has run Furuya's adaptation of Sion Sono's Suicide Circle - a movie known for its opening in which 54 teenage schoolgirls leep to their death in front of coming train. It ran Blade of the Immortal creator Hiroaki Samura's Bradherley's Coach - a short with worth the disquieting edge of the human experimentation in BOI with the brutality more in line with the torture illustrations of his Hitodenashi no Koi. On the other hand, Manga Erotics F also runs Fumi Yoshinaga's Not Love But Delicious Foods, based on her experiences escaping her demanding work schedule by going out to eat.

Lychee Light Club is inspired by the Grand Guignol theatre tradition... Furuya explicitly states as much. But, before speaking to Lychee Light Club's rich, interesting artistic connections, it is essential to note that the work does stake out a place in genre manga. It belongs to a thread of horror manga concerned with hang ups. There might be Dead Wet Girls and other nasties involved, but, essentially, some Tell Tale Heart gets beating in the subject's head, and in the resulting panic, houses come crashing down.

The works of Junji Ito offer perfect examples of this. Ito's victims become fixated on something... a girl (Tomie), a shape (Uzumaki), a smell (Gyo). Ito has a Lovecraftian view of human fragility that is accentualed by a degree of gauntness in his character. Apply the right pressure and people crack. Get people thinking about spirals and before you know it, ready to deliver pregnant women are attacking other hospital patients with hand drills.

Lychee Light Club has more than its share of messiness. There's disembowelments, broken bodies and bleeding out. But, this is a pristine shell getting cracked. Rather than Ito's slightly disheveled normality as a starting point, Lychee Light Club falls from the perverse fascist regularity. The manga opens with the sharp lines of flash light beams and further contrasts of a chess board before resolving into a trial in which the Light Club proposes an intruding peer be fed his own eyes or castrated.

This is aestheticized ultra-violence from a tradition of aestheticized ultra-violence.

"Ero guro nansensu" (erotic, grotesque nonsense) was an artistic movement of Japan's Taisho era, a liberal time, also known as the "Taisho democracy," between the rapid modernization of the Meiji period and the war time that would open the Showa. I don't think Germany's Weimar Republic is an entirely misrepresentative comparison.

The movement looked to precursors in ukiyo-e prints like the infamous sea creature erotic encounter, Dream of the Fisherman's Wife and found itself tied into true crime sensationalism, such as the 1936's Sada Abe case, in which a woman strangled and castrated her lover, then carried around the severed organ in a bag. It would inform the abnormality infused work of Edogawa Rampo, a titan in Japanese crime and sci-fi fiction.

Many forms of media still look back to ero guro, but, relevant to this column, its imprint can be seen in the work of manga artists such as Suehiro Maruo.

Amazingly in retrospect, Suehiro Maruo started in manga sending submissions to Weekly Shonen Jump, but in the 80's curved his niche with work that looked back to ero-guro and its precursor, muzan-e "atrocity prints," Yoshitoshi's 'Twenty Famous Eight Murders with Verse' illustrations of notorious murders and tortures. Fastidiously Maruo worked eye licking deformities and profound wounds into manga like Mr. Arashi's Amazing Freak Show and the notorious "Planet of the Jap" (included in Comics Underground Japan), in which Japan wins World War II, drops atomic bombs on Los Angeles and executes General Douglas MacArthur.

Beyond the Taisho uniforms and interest in the perversity of fascism, Lychee Light Club makes explicit reference to Maruo. In a flashback, a whiskery, wall eyed fortune teller known as Marquis de Maruo told a young Zera "there's a Black Star' over you. A star not even Hitler had.. Kid, you're either gonna rule the world at 30 or die at 14."

Furuya addresses these dark influences in his own particular way, which is as he describes himself "conscious and capricious."

Back around 2006, Dark Horse released a blitz of horror manga including comedian Toru Yamazaki's Octopus Girl - about "super-cute goody two-shoes" Takako or "Tako"/"Otopus." Local stress relieving activities included tying Tako up, gagging her, and jumping on her chest until her lunch comes out her nose. This bullying was taken too far when Taka was force-fed her namesake, invoking an allergic response. The immediate reaction is profuse vomiting, but that night she dreams of an octopus creature... and the following day she wakes up a human head on an octopus body. Problematic, but less so after a bit of a skewed Little Mermaid retelling (closer to Anderson's than Disney's) leaves her with the ability to assume a human body.

Octopus Girl and her Eel Girl rival companion travel out into the world looking for fame and love, and instead find themselves covered in excrement, mucus and blood. There, Octopus girl would use grotesque visuals to shock rather than has a consequence of a disquieting progress and more for astonished laughs than horror. Think Fractured Fairy Tales with a lot more shit and gaping wounds. However, it was hard to imagine anyone, even those who love a good human waste gag, finding much mirth in Octopus Girl. Toru Yamazaki's joke was that he was writing horror, turned comedic, turned back to horror. It's not so funny when there's a bleak subtext to how, repeatedly, Octopus and Eel shake off past failure, chase love and fame and, repeatedly, the inevitable ugly subsequence spell out how hollow those pursuits were.

Putting another bend on that horror/comedy link, Furuya continually turns the whole think back in on himself. Mishiviously unpredictable, it's never quite certain when Furuya is going to wink and when he's going to needle. When the Light Club send Lychee out to bring them a girl, the first he grabs is a store display doll. The club tells him to bring back something with more blood and vitality, so he snatches an overweight older woman. He later grabs include an unhealthy looking guy with long hair, bald on top. The Club tries to teach Lychee the concept of beauty, and the artificial man responds by asking if the curves on a discarded toilet make it beautiful. Furuya is both keenly aware of the absurdity as well as terrible implications, and, he's keen to make both bear fruit.

Lychee Light Club is an example of why, if asked if I prefer anime or manga, I’ll answer in favor of manga. So much anime is made for so few audiences. Far more often than not, it's for kids who can be sold some ancillary or dedicated anime fans who can be sold something. When you get some idiosyncratic it too often seems out of shape from lack of practice.

While it's best not to view manga production through a too rose colored lens, it does offer opportunities for creators like Furuya the opportunity to hone the skill of authoring works of as well constructed distortion as Lychee Light Club. There's abundant evidence that an audience for shocking, trangressive and graphic exists. Making an art of "fucked up", there's no reason why the attention that it receives should be restricted to just manga followers.