Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Live Action Spotlight: Vampire Girl vs. Frankenstein Girl Released by FUNimation

As with most, if not all, of these extravagant, Japanese splatter movies, Vampire Girl vs. Frankenstein Girl is best watched as a social experience in which you and your compatriots aren't applying a critical, clear thinking mindset. Always going far further than needed to make sure that the viewer can see and hear the transgressions being committed, it's not exactly a movie that needs be to engaged soberly anyways. Those arterial geysers aren't the same if you can't turn to a person next to you and snicker or roll your eyes. Aggressively looking for the reaction, Vampire Girl vs. Frankenstein Girl stamps the too much is never enough MO early in with the vampire teen brawling with a trio of loli-goth attire clad Frankenstein girls in black uniform, adorned with red trim and black lace, dripping blood from their joints. The vampire bites the nearest, and with the slice of skin she takes off, she unwinds the rest of her foes dermal tissue. The still animated skull is catapulted, such that the mindless, chomping cranium of the first Frankenstein girl slowly, gruesomely sucks the skin off the next. The third is subjected to a particularly unpleasant stem to stem method of decapitation. Though some movies of Vampire Girl's type are jokingly angry or downcast, this one is not an angsty, morally conflicted vision of vampires, or any monster for that matter. Maybe you can read something nihilistic into the cast's deep sublimation of their issues (a notion captured brilliantly in horror black-comedy manga Octopus Girl; track it down), but, in practice, no one here of consequence minds being out of their mind. Announcing this, that early confrontation showcases one of a number scenes of the vampire girl dancing through showers of blood. Vampire Girl vs Frankenstein Girl's lineage is more interesting than just "based on the manga." Personally, I'm fascinated by splattery manga by women, whether it's Q Hayashida's baroquely strange story of sorcerers getting their faces chewed off by a lizard man, Dorohedoro, or the undead excess of Rei Mikamoto's Reiko the Zombie Shop and Big Tits Zombie. Fans of transgressive Japanese movies might know this story's creator, Shungiku Uchida. She was the mother in Miike's Visitor Q. Beyond her acting stints, the novelist and essayist had her semi-autobiographical prose work Fatherfucker adapted into live action; and, she's produced manga that has hit subjects from porn to pregnancy. David Kalat's "J-Horror" argued that the "dead wet girls" movies had the characteristics of an artistic school and not just a chain of movies capitalizing on the commercial success of each other (though it was that too). If you accept that, you can see something similar with the creative collaborations and branching found in these shock driven gore fests. And here, the usual suspects gather with some friends to make a live monster out of Shungiku Uchida's work. Yoshihiro Nishimura (Tokyo Gore Police, effects work in The Machine Girl, Suicide Club and Meatball Machine) and Naoyuki Tomomatsu (Stacy: Attack of the Schoolgirl Zombies, which featured Uchida, and Maid-Droid) team up to direct. Handling the fights, you get to see Tak Sakaguchi's (Versus, Azumi, Godzilla: Final Wars) again. Bikini and cowboy clad lead of the zombie fighting flick Oneechanbara: Chanbara Beauty Eri Otoguro is the titular Frankenstein girl. Kanji Tsuda (Jun-on, one of the movie's better geek moments is a language lecture from Takashi Shimizu that devolves into a guide to all the Jun-on/Grudge variations) turns up as the Doctor Frankenstein equivalent. Audition's notorious Asami Yamazaki, Eihi Shiina has a small role as the vampire girl's mother. The regular crew of this school of extreme movie turns out in number, along the lines of Yukihide Benny as St. Francis Xavier and Tokyo Gore Police writer Maki Mizui getting screen time as the head of a wrist cutter clique. X-Men by way of this school of horror, Mutant Girl Squad has a segment in which the protagonist pretty much kills an entire community after they try to stuff her and mount her in their mall. It goes on and on, hitting a sort of runner's high of shamelessness. The zenith for the domain reached there is a tricky reaction for these movies to chase. The break from the realm of what is generally considered acceptable into total insanity is most potent when it feels natural or spontaneous. Try too hard, make the audience aware of the effort, and the movie courts rejection. With knowing irreverence, Vampire Girl vs Frankenstein Girl tries to be cool out its spiral into giddy goriness. Takumi Saito as the male lead (live action Yamato, Miike's Thirteen Assassins) serves as normalized control center, with the attractive actor as a well adjusted guy who isn't pleased about the death and dismemberment kicking up around him, but isn't pulling his hair out either. At the same time, it goes to the hilt as much as any of the field In the movie's frequent ventures into painting the town red, it gets into the spirit of presentation, often turning the bloodletting into a musical number with dance or kabuki (which I guess is dance too). Standards for plotting this sort of movie are not particularly high, and Vampire Girl vs Frankenstein Girl's characters are supposed to be types more than realized individuals. That said, it did manage a turn that was good enough for another recent, well regarded vampire movie. And, a couple of hilarious bits of foreshadowing add to it's staying power as a movie that can be rewatched. It does however get into some trouble with its approach to being half smart. You want these movies to get carried away. Transgression is their raison d'être. But, an American audience will find one particular joke to be punching above its weight. Vampire Girl vs pokes a lot of fun at subcultures. Loligoth, cutters and ganguro in particular. The loligoth bits are largely aesthetic. The cutters go a bit further into the comically extreme, with a laughable club of self mutilators... it's an icky idea, but not the movie at its most excessive since the gag is that the girls have so much scar tissue, they can't really cut themselves anymore. Then, there's the ganguro, a sort of black face tanning that is further accentuated with bright makeup around the eyes and lips. Translated as the "Super Dark Club," the movie has jokes along the lines of what it applied to the cutters, with the group insisting on black coffee and that caffeinated black chewing gum. But, the "super dark" girls also, carry spears, with lip plates or other prosthetic make-up and bang on a drum chanting "Obama! Change! Yes we can!" For an American audience, the rest of the movie isn't quite so charged that it can get away with a minstrel act. Then again, seeing a movie like this do something it shouldn't is the reason to watch, especially if you can commiserate and share an eye roll with a group.

Manga Spotlight: Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service Volume 11 By Eiji Otsuka and Housui Yamazaki Released by Dark Horse Manga

During his appearance on the Anime World Order podcast, writer/translator/localizer Matt Alt briefly discussed the Oshii Ghost in the Shell movies. In the anime, conversing cyborg law enforcement officers quote and paraphrase philosophers. The way that Alt frames this is that what's going on is that the wired minds are pulling perspectives from the internet. It's an advanced form of what goes on today when people have their smart phones out to check Wikipedia and pull facts as they talk. That sort of framing of communication by way of technology came to mind reading Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service. It's not that this manga has the same annotated structure. Instead, Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service reads like horror written as if it were a work of blogging. Writer Eiji Otsuka comes to this with knowledge and intelligence. His college degree is in degree in anthropology, with studies in women's folklore, human sacrifice and post-war. He's been a critic and a magazine editor. Early on, the appeal of Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service looked a macabre proposition, in which the reader would be treated to a parade of realistically rendered cadavers in exotic circumstances. Yet, as the series got running, those shocking visuals were tagged as punctuation in a more interesting discussion. Otsuka's Scoobie Doo cast of proxies are intelligent and well educated, and ostensibly dealing with corpses because they're underemployed. The events around the deaths that they unprofitably investigate are often built on top of Law and Order "ripped from the headline" hot button issues. Otsuka then fits those issues together with other subjects that interest him: folklore, history, bits he might have read in recent science journals and geek esoteric fascinations. The proceedings are blog-like in that they're engaged; socially concerned; expert at connecting ideas and expert at provoking reaction. The track record for thoroughly developing the ideas is a bit more mixed than introducing them. The second of volume 11's two stories works the trick of smartly conflating ideas that like likely complementary thoughts. In this case, those super Speedo swim suit from the last Olympics, zombies, and a bit of urban wild life. It's not the celebrity branding grafted onto plastic surgery, the ear mouse, jinmenso (a supernatural tumor with a human face) and multiple revenge plots seen in volume seven, but still an impressively geeky approach to horror. The majority of volume 11 is concerned with one the manga's longer cases. The supernatural element that it works with relates to a manifestation of karma that is visible to individuals with the properly developed ESP. Though this feeds the core cast's slowly established background, and though the manifestation is effectively creepy, the main attraction is Otsuka manga-blogging. The person who has that karma seeing ESP and the foundation for the story is the "Class Cutter," a girl convicted of killer her family with a box cutter, now being reintegrated into society. This is an unsubtle reference to the Sasebo Slashing case that spawned the Nevada-tan. In 2004, an eleven year old girl killed her classmate with a box cutter. Though police initially followed the convention of referring to her as "Girl A," her name was leaked in the media, after which she became known by a class phone in which she wore a University of Nevada, Reno sweatshirt. An internet meme grew out of the abstracted image of a girl in a "Nevada" sweatshirt carrying a bloody blade. Meanwhile, more serious conversation debated the gender, linguistic and legal implications of the case and its handling. Otsuka looks to engage the subject and not just evoke it. He builds narrative tension out of the question of whether a child convicted of a heinous crime can return to a normal life, pulling on the readers empathy with the subject being bullied by peers and disregarded by adults. He further shifts the case to see what something like it might say about the broader society. His reoccurring cast offers him a useful tool for this. The composition of personalities involved are such that it does not sound unnatural for them to act as a mouth piece to question or commentate. They explicitly discuss why Japan has such a high conviction rate (widely reported to be over 99% in criminal cases). Last summer, my mother was doing some gardening when she slipped on a shed's wet ramp. When she went to have her bruises checked out, the nurses and doctors all wanted to heat the "narrative" of how it happened. They responded to her insistence that she slipped by looking for holes in her story, since they strongly suspected that there was another explanation for the injuries. Through Kurosagi's characters, Otsuka says that a person, especially child, can't compete with an accepted narrative. It is an idea that he's dealt with outside manga. In 1989, Tsutomu Miyazaki was arrested for the murder of four girls. Well over 5,000 anime and slasher movie tapes were found in Miyazaki's apartment, leading him to be labeled "The Otaku Murderer," and the reputation of geeks to be truly, darkly blackened for years. In Otsuka's book on the subject, he argued that the media doctored the dipictions of Miyazaki's connection to build up the notion of an "Otaku Murderer." He wasn't saying that Miyazaki was innocent and here, he's not weighing in on the facts of the real Sasebo Slashing case. It's that, when there's a story that can be latched onto to explain behavior, a troublesome echo chamber can be established between publish perception and media. This becomes even more dangerous when it’s allowed to guide prosecution and conviction. This bloggy manga can be better at raising issues then developing them. Otsuka is not bad with characters. The titular Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service are certainly well drawn. He's not always great with characters either. Secondary, story specific ones can be simply functional. The millstone on this story is an antagonist who is simply a heavy old prev man who serves to narrow the focus on society at large to the specific story, with its cardboard villain. It drags the exercise, reminding the reader that it's fictional, but it doesn't stop it. Despite its flaws, for provocation, there's nothing like socially engaged horror, and there's little horror as socially engaged as Eiji Otsuka's.

Manga Spotlight: Hanako and the Terror of Allegory by Sakae Esuno Released by Tokyopop

Future Diary author Sakae Esuno's Hanako and the Terror of Allegory is an entertaining manga series, and though it does manage the occasional chilling tableaux, Esuno proves better at writing about horror than writing it. Hanako of the title is Toile no Hanako, a popular urban legend about a ghost girl who haunts school restrooms. In terms of American supernatural entities, I can think of the Headless Horseman as something that might have as much traction as Hanako, who appears in countless anime, manga, television and movies; sometimes as an entry in an anthology and sometimes she's the main attraction, as in Yukihiko Tsutsumi's 1995 Shinsei toire no Hanako-san or Akitaro Daichi's 1996 anime (she was especially big in the 90's). In terms of modern Japanese ghost stories, her rival for media appearances might be Kuchisake-onna, the Slith Mouthed Woman, and that one is in this manga's second story. Hanako's role is a key element of the manga's appeal, especially for horror geeks in that the manga aims to offer its own take on a supernatural landscape that isn't confined to or originating in its pages. The premise is that ghost stories grow in the public consciousness and eventually instances of those beings that people think haunt them flower into actual hauntings. A slit-mouthed woman or fish faced man become real. Maybe not the scariest idea, but an interesting one to work from . Teenage Kanae Hiranuma's fixation is that there's a man hiding under her bed with an axe who will kill her if she falls asleep. To solve this problem, she seeks the help of Daisuke Aso, a porn mag collecting young detective, who is himself haunted by two allegories. He hiccups when around the possessed, with the extra clause that, if he hiccups 100 times in a row, he dies. And, Toile no Hanako lives in the bathroom of his office. Volume 1 features the axe murderer under the bed, Kuchisake-onna, and Lovecraftian fish faced men. Elements like Hanako and Kuchisake-onna are improved by familiarity with the urban legends and their media incarnations. Surveying Japan's supernatural population in a book like Yokai Attack!, the trend that emerges is the things that go bump in the night are anthromorphized hang-ups. The yokai stories take the fright of a dark corner, obsession or worry, some wonder of a natural phenomenon, some metaphor or word play that sticks in the mind and gives it semi-human form. David Kalat's J-Horror notes how quirks of Japanese school architecture lead to Hanako stories (among other bathroom horror). Reading Hanako and the Terror of Allegory's attempt to built a story around the inspiration for the horror is improved by familiarity with the subjects that it is considering. It helps to know the game or at least be interested in it to appreciate watching the manga kick around these ideas. If you have some attachment to Hanako stories, the notion that sje enjoys technology because it's literal, and doesn't overload, hide or corrupt meaning the way that humans do, is amusingly novel. While this first outing gets some mileage out of reinterpreting the spooky stories, the manga only ran four volumes, so maybe there isn't too much legs to what the series is doing. While Sakae Esuno isn't about to take a place with the greats of horror manga, when it comes to large images, Hanako and the Terror of Allegory does manage some creepy spectacles. With room for scale and perspective, slit mouthed woman's maw stretching across a room in a double page spread or a page of bodies sinking towards darkness of a submerged point of view are about as good as you'll get from a manga/comic artist who isn't great at horror. As horror, and not just manga about horror stories, Hanako and the Terror of Allegory hits trouble. Ironic for a series that aims to think about horror from a new angle, applying thought to Hanako and the Terror of Allegory's stories crushes them. It opens badly with the notion of a man with an axe hiding under a bed. I was a credulous kid, inclined to over react to campfire stories and the like. The guy with the axe hiding under a bed, in a closet or in the back seat of a car was one of the few I remember not getting me. It's one thing to be chasing some one with an axe, as in the Shining. To lurk in a confined space with a large object that needs to be swung? That doesn't work logistically. Committing the axe wielding killer under the bed to the page early on, the story offers an unintended reminder that the idea is more silly than frightening. I don't get the impression that Sakae Esuno thought too much about how a reader might think about what it's presenting. The manga frequently suffers when the reader engages it. The other stories work off twists that are obvious or aggravating. The fish face man story is particularly problematic with its grasp at unearned gravity, trampling ground that will be very problematic for some audiences. Still, even if it is sometimes bothersome, and often not really scary, Hanako and the Terror of Allegory is Halloween candy horror; a fun snack, not enormously satisfying.

Manga Spotlight: March Story by Hyung Min Kim and Kyung Il Yang Released by VIZ Media

March Story is seinen (older, male audience) manga, running in Sunday GX (home of a couple known gun heated works, namely Black Lagoon and Jormungand) from Korean creators Kyung Min Kim and Kyung Il Yang (illustrator of Shin Angyo Onshi aka Blade of the Phantom Master, and Island, an anti-hero driven horror released by Tokyopop fairly early on). As is common for horror manga, at least for this early segment, March Story is structured as episodic stories of the supernaturally afflicted, joined by a character who witnesses the misfortune. Set in, 18th century Europe, as the title might suggest, that linking element is March. This individual uses an unusual, symbiotic relationship with a type of demon known as an Ill in the role of a Ciste Vihad, hunting other Ills. These supernatural tragedy-catalysts dwell in human made objects, waiting to be found. They then possess their finder, causing the victim to grow horns and raise havoc. As that havoc turns deadly, the horns turn crimson and the possession becomes irreversible. March Story's bloody proceedings are defined by a look that's gothic in the modern sense of the word. And they're defined by being bag of hammer stupid. And yet, the manga overachieves by owning both, neither explaining nor apologizing for its characteristics. In this volume, obvious scenarios with some thorny flair lead up to an amazingly demented back story. And there, March Story begins showcasing some attention commanding wildness. Where the manga had been unessential, the gory history is enough to make March Story prospectively interesting, with a second volume seemly set to cinch whether or not the relatively young series (its Japanese run began in 2008, but it's running in a monthly) is entirely worthwhile. After an violent, pre-credit roll sequence in which March dispatches of a beyond help Ill-fated, the manga's first adventure finds March with eyes on the street looking for a Ill-bound ear ring. March bumps into a girl who also has her eyes on the ground. Dejected Pircolett is the daughter of the ring master in a travelling circus and dreams of being an acrobat, but because she's ugly (giving the tradition of ghastly horror manga from Shigeru Mizuki to Hideshi Hino, the notion of this pixie-ish girl being "ugly" is laughable), is assigned to be juggling clown. Pircolett plucks a muffin off the pavement, and is about to eat it, when March snatches it out of her hands, ominously warning her never to touch something the providence of which she doesn't know, "it could contain dangers beyond human reckoning." March then undercuts the gravity of the warning by taking a squirrel’s approach to quickly consuming the muffin. Of course, Pircolett finds the Ill earring. And, with little hesitation, she ignores March's warning. Of course, it grants her wish of becoming an acrobat in Monkey's Paw fashion. There's plenty of bloody bodies and tears, but, setting an odd precedence for the series, March is able to avert real tragedy. Plenty of iffy manga horror series, including ones for audiences younger than March Story's have attempted to grab the reader by remorselessly going to the jugular in their early outings. The expectation that March Story sets up here is that it travels a familiar path to a destination that is not as dark as it might first appear. Kyung Il Yang is an illustrator rather than a writer, but the introductory story notably contrasts how his other works began. Island opens with its anti-hero savagely beating back the ogres attacking female lead, only to have him cast as a misogynistic serial killer. Shin Angyo Onshi has its law enforcer of an old world order travelling across a crumbling society as a wondering gunslinger. He insists he is not a hero, either in role or demeanor. He sort of goes to rescue a child, and concludes the confrontation by directing a monster's attention towards its child hostage, then shooting the threat in the head when distracted. Despite some tragic endings, the sum of the other one off stories doesn't disabuse that notion that March Story is furiously swinging around a nerf padded horror bludgeon. There's Jake, an older woman with an oversized face approaching that of Spirited Away's Yubaba, who dresses like a loligoth teen. There's a spoiled rich kid who hyper-active Ill corrupted persona is like something out of a Warner Brothers cartoon. The manga version of Chevalier d'Eon is often ripped as silly with its guy interest re-aligned take on a loligoth look. Personally, I thought that there was something amusingly half-clever about the way it looked at the Versailles court and retrofit an extravagant, almost parody of loligoth fashion on the Roccoco aesthetic that contributed to its birth. March Story doesn't employ any such justification. It's a bit Tim Burton's Sweeney Todd shifted further out, with as much black thorns, carnival masks, striped stockings, fringes and stitches as can be packed into its panels. Though unlikely to alienate someone who would identify themselves with the aesthetic, it isn't really position for them. This might seem like it would set March Story up for an identity crisis, but even if the manga isn't presenting conventional lookers, it reads more for like it was for an audience inclined to gawk at loligoth girls than one composed of or sympathetic to them. The fourth and final chapter of the volumes, Black Dream is a back story. It's neither new nor surprising. It's basically an Elizabeth Bathory pastiche. Even if not heart wrenching either, in its favor, it's pitched and relentless. While its gritted teeth and tears are well earned, more than emotionally effecting, it's grabbing. The story offers quite the gesture with all its piling on. It's like going down a flight of stairs, and after a series of evenly spaced step, there's one that's double the height of the previous ones. You might not trip, but you're now looking out for what might be treacherous ahead. Spinning off familiar parables and spooky tales, March Story seems unlikely to develop into smart manga, stimulating its readers emotionally or intellectually. The angles it takes similarly make it unlikely that March Story is going to carve a niche into parameters that a horror purist would be happy to call "horror." Still, if it continues to mix extravagant goth illustrations with situations that put the reader's head on a swivel, it'll slice out an alternative, darkly enjoyable niche.

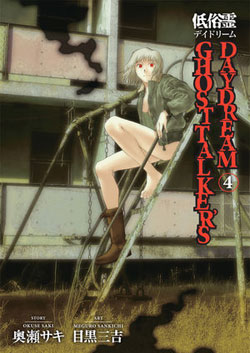

Manga Spotlight: Ghost Talker's Daydream volume 4 by Saki Okuse and Sankichi Meguro Released by Dark Horse Manga

Horror is one of a couple of genres of manga that I'm usually willing to give some leeway, especially if it is truly trying to tell horror stories and not just use horror trappings, as in all the generic stories with vampires. Yet, I was cold on Ghost Talker's Daydream. It ran in Shonen Ace, an anthology known for its many anime tie-ins, such as the Neon Genesis Evangelion manga. As the name applies, it's for a shonen audience, but it skews older than periodicals like Shonen Jump or Shonen Sunday, as it features darkly disturbing, and/or violent works, populated by older characters such as Goth, MPD Psycho, Welcome to the NHK, Kerberos Panzer Cop and Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service. It's explicitly shonen, but borderline seinen (though those more mature titles have more recently more to seinen Young Ace.) And Ghost Talker's Day Dream follows suit, not adhering to firmly deliniated territory for what's appropriate. Manga that hops that the rails can be brilliant, but, Ghost Talker's Day Dream doesn't stick its landing. The concept was hatched by Okuse Saki, who has plenty of horror history, most notably Twilight of the Dark Master. Artist Meguro Sankichi has an effective hand for rendering darkly violent scenes. His fight work is actually pretty good too. As such, it's not a dearth of talent that set the manga off balance. The protagonist here is an medium, and in this difficult economic landscape, she has an extra job or two. She's a dominatrix, and a BDSM columnist. In terms of physical characteristics, she has albinism, and lacks pubic hair. The manga operates under the assumption that the missing hair and the dominatrix works are hilarious. Just evoke them and the audience should be tittering. Along with these frequent misstep attempts at comedy, factor in a meta-creepiness with its lurid fascination with sexual violence, and Ghost Talker's Daydream is a bit of a mess. That said, Saiki Misaki is largely missing from volume 4, and as such, jokes about her career and physical characteristics are absent. Without her holding the center, the super natural problem solving is supposed to be problematic, and the unwound proceeding are effective for telling horror stories. The volume features two cases in which mediums are pressed to investigate the ghostly echoes of suicides. One sees psychotic detective Gada strong-arm traumatized high school student Kunugi Ai into read into why a pair of girls hung themselves outside a temple. The second effort has Ghost Talker Daydream's more frequent organizers mounting the effort. Livelihood Preservation Group's liaison Kadotake Souichirou is fairly in over his head when it comes to the supernatural, but considering he's an unexceptional looking civil servant, thanks to a grasp of judo, he's fairly (and relatively realistically) able to handle the human element. With Misaki away, he brings in Kunakoshi, an Otomo-esque psychic whose abilities don't' impress, to ascertain why a spectral woman is haunting the bridge from which she threw herself. In both, neither the organizer or the medium are really up to task, and even by the standards of horror, neither investigation goes smoothly. Ghost Talker's Day Dream still has problems. There's its leery quality. It alternately aims to titillate and disturb, and doesn't offer much evidence to convince that there's an objective beyond stimulating the reader. If there's reason to be intrigued by the clues to a unifying influence behind the series suicides and other violence, it hasn't manifested yet. And, relevant to all of its flaws, the manga still misses the mark in its human dimension, lacking the regard or sensitivity for its character that it needs to be taken seriously in its dealings with traumatized characters. Still, the unhappiness in volume four is effecting. Humanity ends up looking terribly mistake prone and life cracked with opportunities for tragedy. As demented, ill equipped, or both people content with the ghostly remnants of suicides, the nasty mess makes for Ghost Talker Daydream's strongest entry.

Event News

Giant Robot's GR2 in LA will be presenting Visitors: New Art by Theo Ellsworth November 6th to December 8th, with a reception Saturday, November 6, 6:30-10pmCheck out this to see more work

Digital Distribution

FUNimation has begun simul-streaming charming looking Princess Jellyfish on FUNimation.com's video portal, YouTube and Hulu. The Brain’s Base (“Spice and Wolf II”, “Baccano!”) and Takahiro Omori (“Baccano!,” “Hell Girl,” and “Durarara!!”) series adapts Akiko Higashimura's award winning manga. It is currently running on Fuji Television's noitaminA, which airs anime for audiences who aren't traditional anime fans.