Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Deadline is reporting that Universal Pictures and Despicable Me producer Chris Meledandri's Illumination Entertainment are teaming with Tezuka Productions to adapt Naoki Urasawa's Eisner Award nominated manga Pluto as live action/CG hybrid film. The thoughtfully mature reimagining of a classic Astro Boy story manga was released in North America by VIZ Media. "With Pluto, Naoki Urasawa has defined an imaginative world full of inventive action and adventure but it was his characters and heartfelt story that compelled me towards acquiring these rights," Meladandri said in a statement.

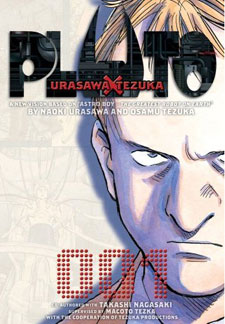

A previously posted look at the manga's first volume.

Manga Preview Pluto: Urasawa x Tezuka 001 by Naoki Urasawa Released by VIZ Media

Naoki Urasawa's Pluto is a Blade Runner re-imagining of Astro Boy, not in terms of plot or environment, but in terms of tension. While the manga deals with a detective trying to find the truth behind two, specific, potentially incendiary deaths, it's not just one troubled individual in the spotlight with a dimmed, inactive world around him. Whatever that detective sees, whether it is a mundane day to day struggle, evidence of a haunting past or an acute tragedy, it does not go away when he leaves the room. The consequences of those deaths may turn out to be apocalyptic, and the worst may be averted, but even then, Pluto projects a tomorrow which is likely going to be trying for all involved. Looking into a disaster plowing through a forest of social problems, this story is palpably stressful. Of all the reaction manga can evoke, few are as likely to cause you to rub your temples as Pluto. I don't know if "not maudlin, but genuinely sad" is a selling point for manga, but in terms of substantial sci-fi, I couldn't recommend Pluto any more strongly. As translated by Frederick L. Schodt in the Dark Horse release of Astro Boy, Osamu Tezuka's laws of robotics start with article 1: Robots exist to make people happy and end with article 13: Robots shall not injure or kill humans. In Turn, Pluto starts with two murders: Montblanc, the beloved robot of the Swiss Forestry service, veteran of the 39th Central Asian War, and poet and Bernard Lanke, a member of the movement to preserve the robot laws with a reputation for attracting enemies. Law 13 is evidently fundamental to Pluto's murder mystery, but law 1 seems equally essential. When I was studying for a BS in computer science, there was a junior year writing requirement. I forget the course title, but it had something to do with technology ethics or principles. So, in addition to learning tech writing, we were supposed to produce written responses to issues like piracy, privacy, life threatening software glitches, the intersections between social problems and technology and the like. While there were no Pollyannas in the class, there was a prevailing sentiment that there was a technological solution to most problems. The trick was to find that solution. I still see that idea around, and not just in the computer science/software field. We're looking for the right technology to save the auto industry, to protect the environment, to fix the economy... Pluto asks, what if we had what we thought we needed? What would things look like if we had everything that sci-fi of the 50's and 60's promised us? What if there were geniuses who could push artificial intelligence to the point where those systems were scientifically proven to possess subconsciousness? The manga seems defined by its sadness. Despite the hover cars and servant robots, humans seem to be of the same disposition that we were at the point at which the manga was written (2003). And, with talk of "weapons of mass destruction," they seem to be engaged in the same mistakes. On the other hand, between fulfilling their functions, contending with both casual and outright bigotry and largely being denied outlets for what could be thought of as their humanity, the robots of the manga look like they’re bearing Atlus' burden. Stripped of how Urasawa actually represents Pluto, many of its scenes verge on being laughable. A detective informs what is basically Rosie, the maid from the Jetsons that her husband Robbie, the police robot was destroyed in the line of duty. A Hannibal Lecter exchange is enacted with a heap of what looks like the robot that attends Luke Skywalker when he gets battered in Empire Strikes Back slotted in for the killer. In the Rosie case, Urasawa illustrates a figure trying to figure out what to do with herself to deal with her grief. She has routines, such as fixing tea, but her ability to express her emotion fails her as she stands with a cup of tea in each hand. She is able to draw a relationship to other experiences she has had and state her sorrow eloquently "I work as a made for a family. And they have a little boy. A human boy of course. Before the boy was born the family adopted a pet dog... the boy and the dog were fond of each other. But then the dog died. The little boy cried and cried for days. I tried my best to comfort him.. but only now do I understand how he must have felt." The image, as well as its implications concerning the world of robots and the less speculative human condition are heartbreaking. One of the classic, memorable stories in Osamu Tezuka's Astro Boy is 1964's "The Greatest Robot on Earth," also known as "The World Strongest Robot" (published in volume 3 of Dark Horse's release of the series, unfortunately, the only volume I can't find from my collection at the moment). Filling a volume of manga, and running two episodes in the 1963 and 1980 anime incarnations, it's one of the longer Astro Boy stories. Generally, the longer Astro Boy stories find their length by twisting and developing in unexpected directions. In contrast, The Greatest Robot on Earth is obviously a big one from its inception, and its premise enables it to work like a modern graphic novel narrative. A power hungry Sultan commissions the creation of the robot Pluto and sends the million horse power titan out into the world with the mission to destroy the seven most powerful robots, thereby commanding a spot as the king of all robots. With Pluto, Astro and six other super-powered robots battling across the globe and with heartfelt exchanges between Astro, Pluto and Astro's sister Uran, it's both a perennial favorite and one of the Astro Boy stories with the most potential to capture a new reader. One of the seven robots was the gold, "Zeronium" plated detective known as Gesicht (Zeron in the dub of the 1980 anime), who took up the mission of apprehending Pluto and determining his motives. Despite Gesicht's intellect and robotic abilities, a fight between the two ended tragically for Gesicht. Tezuka's stories depicted robots that looked human, and there were cases where humans could be mistaken for robots and vice versa. While the Gesicht of the Greatest Robot on Earth was a golden figure with gadgets protruding from his chest, Pluto's Gesicht can pass for human. And like a human, he is haunted by nightmares, exhaustion, the fear that he is an inadequate husband and inadequate to the task at hand. The notion of a more "adult" take on a popular children's character has been around long enough that its parodies have become obvious. This isn't to say that familiarity should breed contempt. In recent years, we've seen both straight mature variants (Batman Begins) and parodies (Venture Bros.) that have been quite exceptional. It's that the concept is now far from novel and Pluto does not get credit for simply being Astro Boy for an older reader. Pluto is not Astro Boy with the violent or sexual signifiers of a mature work. Though, you were never really going to get that excess in a non-doujinshi manga. As related in The Astro Boy Essays, Urasawa approached Osamu's son, Macoto Tezuka in 2002 about his ideas for Pluto. The Tezuka family is protective of Astro Boy, and were especially so in the time leading up to the 2003 planned relaunch of the Astro Boy phenomenon. After meeting with Urasawa, Macoto Tezuka agreed, according to Essays, on the condition that "Urasawa would not create a mere homage or parody, but do something original." And Urasawa has succeeded in creating manga that is as sophisticated and unique as any in his own award winning body of work. Pluto ran in seinen (older teen/adult manga audiences) anthology Big Comic Original, which has also been the home to Urasawa's Monster and Master Keaton, the 35+ year long baseball manga Abu-san, Haguregumo by the controversial George Akiyama and the dramatic omnibuses Rumic Theater (by Inu-Yasha creator Rumiko Takahashi) and Human Crossing (anime versions of which were released in North America by Geneon). As with the manga tradition itself and genres of manga within that tradition, no anthology is entirely monolithic in its traits. That said, characteristics do emerge. Among seinen, anthologies, you can look at Afternoon and note the presence of Hiroki Endo's Eden: It's an Endless World, Hitoshi Iwaaki's Parasyte, Mohiro Kitoh's Shadow Star/Narutaru, and Hiroaki Samura's Blade of the Immortal. Given the commonalities of those work, you can say that the anthology has a place for manga that mixes blood splatters and metaphysics. At the same time, with works like Hitoshi Ashinano's Yokohama Shopping Trip, Kenji Tsuruta's Spirit of Wonder and Yuki Urushibara's Mushishi, you can say that Afternoon also has a home for more subdued, contemplative works. If you look at Ultra Jump, with Yukito Kishiro's Battle Angel Alita: Last Order, Hirohiko Araki's Jojo's Bizarre Adventure spin-off Steel Ball Run, Oh! great's Tenjo Tenge and Kazushi Hagiwara's Bastard!!, you see a collection of what could be thought of as graduated versions of shounen. Not to say that the insight for how to handle introducing an adult perspective into Astro Boy was hatched by the Big Comic Original editors rather than Urasawa, but looking at the anthology's works, it is noteworthy that the series are more about a human dimension than they are visceral shock and awe. Likewise, Pluto is chiefly concerned with the weight of decisions, society and history on its characters and offering a chance to witness how those characters think and react. Minor spoilers... There is a scene in which Gesicht takes a lunch break to books a trip to Japan. Distracted by considering witness testimony about the Lanke case, the conversation swerves into a blindside when the holographic projection of an attractive travel agent asks him what might be a pointed question. "Forgive me for asking, but will this be your first trip?" "First trip?" (I believe this get sensitive quickly because, as listed in Schodt's Astro Boy Essays, the fifth robot law is "Robots shall never go abroad without permission.") Gesicht mutters that it is in fact his first time travelling to Japan, where upon the agent asks "excuse me, but both you and your wife are robots aren't you?" Gesicht goes from half attentive to knowingly sad as he responds "why yes... any problem?" The agent then informs Gesicht that she too is a robot, she's a bit envious of the trip and finds Gesicht's intension of taking his wife to be sweet. "Well, she deserves a trip... after all, she's had to put up with.... I'm usually too busy to pay her much attention." This is an unguarded moment for Gesicht. In the cafeteria foreground we see a detective had been scowling and barking about Lanke, relaxed to the point where he looks half asleep as he listens to his holographic conversation partner. Compared to the visible tension in Gesicht's shoulders, and expressions that might indicate that he was on the fast track for an ulcer if he were human, his yo-yo shifts between pleasure, knowing distaste and back seem mild. It also seems telling that he is prepared to be face with bigotry, even in the middle of receiving a sales pitch. Again, the "robots exist to make people happy" dictate echoes in this exchange. During the course of the volume, another peer of the seven strongest/greatest, who like Montblanc fought in the 39th Central Asian War, leaves his warrior role with aspirations to play the piano. It's a tragic story. In a way the smiling travel agent is just as tragic. To her, the exchange with Gesicht seems to signify freedom that some robots can obtain, even if it is out of her personal grasp. She's a person who explicitly exists to make others happy, seeing at least some people in her position can find a release. And she does it with a smile on her face the whole time. To distill this into something even more mundane, within a couple of pages, Gesicht will mention that he can tell a robot from a human by the superfluous movements that humans make. It might be that he was distracted, or a function of the holographic technology, but he is visibly taken by surprised when he hears that the agent is a robot. A subtle comment about Gesicht's personality, or a subtle comment about the position of sales people? End spoilers For anyone enthusiastic about Tezuka lore, Pluto is a must. Like Tezuka might have done himself, Urasawa pulls in other figures from Tezuka's body of work. Volume one has at least one cameo that will have fans grinning ear to ear. Beyond that, the manner in which Urasawa works within the framework of the Greatest Robot on Earth is sure to be a pleasure for anyone familiar with the original. For example, one the seven who tracks down Pluto to pick a fight with rampaging super robot is the Turkish wrestler Brando. In the original, he turned up to avenge his friend Mont Blanc. The exchange was more about Astro and Uran trying to stop the fight before Pluto did something terrible than it was anything in terms of deep characterization on behalf of Brando. Urasawa works out a fully developed philosophy for the character. Everything about him is interesting, from how he views on robot wrestling competition to how he establishes a personally fulfilling place within human/robot society, to how he believes that he can deal with Mont Blanc's killer. Yeah, you can kind of see this as fan service, and yeah, you can see the excitement that Urasawa felt after finally convincing Tezuka's family to let him work with one of the greatest casts in the manga tradition, but at the same time, Urasawa's talent for characterization really has an opportunity to produce an effecting, provocative story with this framework. A reworked version of the World's Strong Robot via the 2003 Astro Boy on Hulu