Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Genius Party by Studio 4°C Available with English subtitles on Region 4 DVD via Siren Visual

Studio 4°C

American anime watchers are not out of line when they rattle off "Ghibli" and "Hayao Miyazaki" as the first names in a list of revered figures and institutions in anime. The same gravitation governs nearly every watcher of the medium. You don't, or shouldn't need to drill too much further into the prestige list to get to the name Studio 4°C. Formed in 1986 by Eiko Tanaka (producer on My Neighbor Totoro), Koji Morimoto (animator in Animatrix: Beyond, with a history going back to Ashita no Joe) and Yoshiharu Sato (animation director on My Neighbor Totoro, key animator on Kiki's Delivery Service) the Ghibli connection is unavoidable. Roland Kelt's Japanamerica quotes Tanaka as saying "five years from now, we would like to have accomplished as much as Miyazaki and Ghibli have, and reach to the rest of the world as he does." Yet, there are stark differences, exemplified by the raised eyebrows reaction to Studio Ghibli's recent announcement that a director who had not previously directed a Ghibli film will be helming an upcoming project. Ghibli produces Hayao Miyazaki movies, Isao Takahata movies, and movies in the style of Miyazaki and Takahata movies. Even then, evidence suggests institutional conservatism, especially in the light of box office under performance. Works that veer off too far, like Takahata's comic strip adaptation/family study My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999) and Hiroyuki Morita's distinctively animated fairy tale the Cat Return (2002) don't seem like territory Ghibli is eager to revisit. The production of Spirit Away (2001) is a story of possible deviations from the Hayao Miyazaki standard turned back into a classic implementation of his vision. Tanaka said of said of Studio 4°C "I wanted to make a place where creators who wanted to make interesting work would naturally gather." Studio 4°C has become known as one of the least hidebound institution in anime. In a male dominated industry, Tanaka's position in and of itself sets the studio apart. Under her stewardship, Studio 4°C has gained a reputation for their independent spirit, their digital work in movies like Spriggan and Steamboy, as a go to for anime incarnations of large IPs of western origin or interest, as in Animatrix, Batman: Gothman Knight, Halo Legends and Street Fighter IV, and bringing unexpected voices into anime, such as American digital effects artist ( The Abyss, Fat Man and Little Boy) turned director Michael Arias' role as director of TekkonKinkreet.

Shorts and Genius Party

Studio 4°C has a history of anime shorts that's evident from the Matrix and Batman collections, and, if you stretch definitions a bit, ads like Nike's Chamber of Fear (and the Honda Edix kiro spot and music videos for artists including Linkin Park ("Breaking the Habit"), Ayumi Hamasaki ("Connected"), Hikaru Utada ("Passion") Back in the 90's, when anime was taking off in North America, there was a rudimental of schema outlined for how to understand the industry. In order of per minute animation budget, there was TV series, original video animation (OVAs) and movies. OVAs looked better than TV. Movies looked better than OVAs. A significant reason for why this is no longer reiterated very often is that it is no longer very useful. Largely due to economics, OVAs have lost their role as a home for trying out ideas that don't fit elsewhere and for bringing manga or novels to new audiences. The few that are still produced are often packaged with limited editions of manga. Apart from the annual movies connected to Pokemon, One Piece and like franchises, there has never been a tremendous amount of anime movies produced. Still, it has become an occasion when a Paprika (2006) or a Girl Who Leapt Through Time (2006) is released. Beyond being out of date, that model of anime overlooks the role of shorts. As discussed in this columns Astonishing Works of Tezuka Osamu feature, anime shorts represents a alternate course for animation, apart from one in which it is a product shaped by the dictates of sponsors and audience appeal and more about artistic experimentation and expression. For the sake of taxonomy, I'm going to group shorts produced to stand alone, perhaps shown at festivals and shorts produced to be shown in anthologies. Prior to laying out the template for how to produce anime for TV with Astro Boy in 1963, Osamu Tezuka stepped out from the industrial production process by which studios like Toei Doga were make anime movies and created his own artistic statement. 1962's Tales of the Street Corner was Osamu Tezuka declaring himself as an animator willing and able to define his own process. He founded Tezuka Osamu Production, soon renamed Mushi Productions, with the intended business model of producing commercial anime to fund experimental works. Mushi's 1973 bankruptcy illustrates the financial precariousness of the idea, but what has remained is the notion that TV anime is the domain of fighting with budgets and sponsors while shorts are the closest arena that anime might have to auteur works. Studio 4°C has made their mark in the field of anime shorts with their anthology collections. Of these, the triptych of Akira creator Katsuhiro Otomo manga adaptations, Memories (1995) is available in North America, and actually schedule to be available through Netflix streaming starting November 6th. It's entries include Magnetic Rose - Solaris meets Madame Butterfly, directed by Koji Matsumoto, with a script anime-director-to-be Satoshi Kon (Paprika, Paranoia Agent, Perfect Blue), and music by fan favorite composer Yoko Kanno (Cowboy Bebop) Stink Bomb - Akira meets practical joke, directed by Tensai Okamura (Wolf's Rain, Darker Than Black, Project Blue Earth SOS) from an Otomo script with music by Jun Miyake Cannon Fodder - 1984 meets Kafka, written and directed by Otomo, with music by Hiroyuki Nagashima Other collections, not available here, include Digital Juice - featuring Lords of the Sword by Hidekazu Ohara, Chicken's Insurance by Hiroaki Ando, Kin Jin Kitto by Tatsuyuki Tanaka, In the Evening of a Moonlit Night by Kazuyoshi Yaginuma and Table and Fisherman by Osamu Kobayashi of Beck, Paradise Kiss and Gurren Lagann flame war controversy fame Sweat Punch - featuring Professor Dan Petory's Blues by Hidekazu Ohara End of the World by Osamu Kobayashi, Comedy by Kazuto Nakazawa, Beyond by Yasushi Muraki and "Junk Town" by Nobutaka Ito Amazing Nuts! features Global Astroliner, Glass Eyes, Kung Fu Love - Even If You Become the Enemy of the World and Joe and Marilyn For Genius Party, Studio 4°C's unifying themes were energy, freedom, and creative license. The project catchphrase was “seiyaku zero" - zero restrictions. The result is collection of work that broadcasts passion for creation. Part of the legacy of Astro Boy is "Tezuka's Curse." When Tezuka signed a TV deal for the series, he underbid the production, hoping to block competitors from entering the field. As such, making money off anime has always been dicey and generally required the involvement of sponsors. While fans might wish to think of it as the domain of daring, revolutionary work, it has intrinsic proclivities towards banking on easy marks... producing titles for kids and already dedicated fans... redefining and reiterating past successes. The danger of static predictability is a looming one. As such, works like Genius Party constitute a much needed exercise for the medium. It's not an "eat your broccoli" for the viewer, but watching its yoga stretches isn't always brilliantly fun. Some of its entertaining, some of it is worthy and some is both, but it's all an interesting demonstration of what could be done in the medium.

"Genius Party"

The title sequence features the work of Atsuko Fukushima, another veteran of Ghibli, and anime in general. Entering the field from a textile background , her earl work includes key animation on Kiki's Delivery Service, graphic and key animation on Akira, Dagger of Kamui, and Golgo 13: The Professional. Fukushima previously worked with Studio 4°C on the Magnetic Rose segment of Memories, the Beyond segment of AniMatrix and the studio's Utada Hikaru music videos. As wrongheaded as it may be to identify female creators by association with their spouses (see Moyocco Anno), it is interesting to note that Fukushima is married to Studio 4C cofounder and anime shorts maestro Koji Morimoto.Relevant to Genius Party, her previous shorts work includes the fantastic opening sequence of the Robot Carnival (1987) anthology. In that marvel, a boy in Tatooine meets cartoon quasi-Mexico environment catches a flyer blowing in the wind. Terror crosses over his face as he sprints towards his village. A titanic machine, shaped as the words "Robot Carnival" plows through the desert. Panels open up and the music by frequent Hayao Miyazaki collaborator Joe Hisaishi swells. As the robot strike up their orchestra and pirouette, they unleashed a holocaust of missiles and bombs that level the scared town. Though Robot Carnival was a Sci-Fi channel mainstay back in the 90's it has sadly never made its appearance on DVD in North America. The eponymous work of Genius Party is similarly set in a strange desert-ish landscape. It's a simple story, presenting a clear metaphor. Smiling stone skull/brain/eggs litter the sand, occasionally burbling fluorescent hearts or sparking neuron shapes into the air. A sort of bird/birdman/costumed thing dances over to one of the stone minds, cracks its beak in and pulls out a heart as if the cartooned essence was a worm. Consuming it, the bird ignites in inspiration, taking to the sky and setting off a chain reaction that brings the mindscape to life. The short evokes Burning Man more than it does "anime." With a sky that looks pasteled onto a canvas, the tableau feels like dreamed artifice. Despite its naturalistic movements, the subject creature has the look of some unique construction between its asymmetry and string and boards texture. Weighed by these impressions, in recording the process of consuming and igniting, the short seems to be spying on a display, both animalistic and performance. This wonderful looking piece sets the right opening notes for the collection. Even as thunder clouds roll in, its mix of imagination and excitement stand in stark contrast to the trepidation (or abject terror) presented by Robot Carnival. Fukushima is representative of the group working in Genius Party: fresh and innovative, but not really a new voice. Rather than a rampaging experimentation, it's sparks of inspiration from skill creators with track records.

"Shanghai Dragon"

Shanghai Dragon was directed by Shoji Kawamori, who is both a prominent and an interesting figure in anime. Kawamori studied mechanical engineering at Keio University before becoming a mech designer for Captain Harlock (1978) and Takara's Diaclone (1980) toys, the basis for many of the original Transformers. He made a name for himself by designing the transforming jet/humanoid robot Variable Fighter and other mecha on Super Dimension Fortress Macross (1982), the first part of localized amalgamation Robotech (1985). In what's supposedly a "one for me, one for them" arrangement, he went on to envision and supervise Macross' OVA project Macross Plus (1994) and tv series Macross 7 (1994). Plus was a four episode OVA, later re-edited/partially reanimated and rework into a movie, that took a more mature look Macross' key ingredients: war, music and a love triangle - feature the unhappy, adult reunion of three troubled, childhood friends. The work featured Cowboy Bebop's Shinichiro Watanabe co-directing and Yoko Kanno on music. Macross 7 was a zanier, more pop next generation continuation (the title refers to the name of the flagship in a space colonization fleet, it's not the seventh Macross series) He'd continue this leadership position on prequel Macross Zero (2002) and the recent Macross Frontier (2007). He also had a similar creator/supervisor role for Vision of Escaflowne (1996) - a key entry in the 90's North American fan canon. The TV anime series started with a girl from our world with interests in track and tarot. Thinking that she sees a boy with whom she's infatuated, she stumbles into a confrontation between a wild haired young man with a sword attacking a dragon. Whisked into the fight, she's transported to the world of Gaia, where Earth can be seen as a "mystic moon" in the night's sky. That boy proves to be the prince of a kingdom about to be overrun by knight's armor-like giant robots. The girl not only becomes romantically entangled with the prince, but also with a debonair vassal knight who resembles her school crush. With Romantic Nobuteru Yuki character design, soaring Yoko Kanno music and animation that established an original place for the anime's events, it grabbed the attention of anime watchers. With that attention it proved to many that anime can constitute complex mix of ingredients, appealing to both genders; comparable to Final Fantasy VII, before Final Fantasy VII. It wasn't simply for male viewers or female viewers. It could engage everyone. The less said about the debacle of trying to edit the series for a Fox Saturday morning cartoon run the better. The other noteworthy element of Escaflowne was its ending. Escaflowne was inspired by Kawamori's ideas for reworking the fundamentals of Macross as shaded by his ruminations on fate and divination during a trip to Nepal. This dominated the late part of the series, which proved to be a bewildering venture into natural philosophy, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle and mysticism. Popularity begets freedom, and what anime fans soon got a chance to learn was a) Kawamori is a spiritual guy. B) A social and ecological consciousness stem form that spirituality. ) He's not afraid to share these beliefs.As much as Kawamori's imprint on anime has been as the mecha designer and banner carrier of Macross, he's also become the macrobiotic eating, spiritualist director, whose interest in those subjects doesn't always stop short of alienating the audience. (hence the irony when he gets involved in the Macross machine, promoting branded creampuffs and the like). This mix of tech and mysticism has become his brand. As executive director of Satelight, he's been part of a studio that has produced works like Noein (2006), underrated quantum physics, sci-fi anime that might be the greatest Kawamori anime not directed or written by Kawamori and Aquarion (2005) a Getter Robo combining robot tribute with reincarnation and pilots who orgasm when their planes link into a humanoid machine 2001 in particular saw the premieres of The Daichis - Earth Defense Family - a comedy about a dysfunctional atomic family given the roles of global protectors, with weapons/ammunition charges in excess of their pay, and unambiguous social commentary, and there was Earth Girl Arjuna, a sort of Hindu magical girl action series with provocative suggestions for environmental action. Even the lighter Daichis raised eyebrow, and marked Kawamori as an incendiary anime creator. Arjuna's spiritual world view, combined with ecological alarmism provoked some vehemently negative reactions, but that provocation distinguishes it in the field of popular anime. More often, when anime seeks to disturb its audience, it takes approaches that the audience welcomes and seeks. For example, Higurashi-When They Cry or Elfen Lied - anime that draw the viewer into anticipating psychologically or physically grotesque scenes. There's plenty of anime that are potentially offensive, but few look to confront and possibly affront the audience the way that Arjuna did. Given what Kawamori has come to represent, it is slightly surprising that he eschewed risk and turned in the most explicit and approachable entry in Genius Party. Shanghai Dragon is set in Shanghai, with Mandarin language dialog. A literally snot nosed kid is bullied by his classmates. They steal his chalk and scuff off his drawings. Generally he marks himself as the likely, unlikely hero for a work of anime. And, in fact, he's the one that finds a crystal implement in a collision crater. This proves to be a "substantiation of wishes system." It synchs with his brain with a bit of neural network CGI, calling to mind the synapses of the opening Genius Party short, but also a mainstream anime series Code Geass. With brain and crystal aligned (written like that, it does sounds a bit Kawamori New Age), the boy's drawings materialize. At first he brings food into existence. Then, cyborgs arrive with the AI space invaders hot on their heels. After valiantly and flamboyantly gunning away the AIs, the cigar chomping cyborgs scan into the boys head, they see a chaotic maelstrom of super heroes, cars and random shiny objects; prompting the proclamation that the boy could be the "legendary child". The battle's tide turns against the cyborgs and in order to save the day, the child unleashes his imagination... transforming into a sort of snot rocket propelled "Rider" sentai hero. The power of imagination, and specifically, a child's unrestrained imagination is hailed. This fundamental sci-fi tribute is not Kawamori firebombing the scene with holy Peace and Love and "What are you doing to the planet!" as might be expected given the parameters of the project. While it's hard to be sour on the joy of creativity, the original Macross' notion of culture as an effecting force was meatier. Still, the exercise of imagination is bold and colorful. Shanghai looks great as a live environment, built up and inhabited rather than marked out in short hand. Watching the short pan through the city calls the breathtaking Tekkon Kinkreet to mind. Though animation fans aren't going to complain, with nice revolver fu, high speed blaster-behind the back shots and Macross Missile Massacre, most of the it is thoroughly conventional. This is a quality example of modern, digital animation. It doesn't have the studied motion of works like Mamoru Hosoda's Girl Who Leapt Through Time. One cut that stood in my minds featured a crowd classmates absolutely still in the backgrounds as the lead moved in the foreground. While there is figure animation, more often, attention is mainly paid to effects. Of course it isn't simple to give motion to the bursts of light, explosion and blurs as a cyborg guns down mecha-raptors. But, it'd be more interesting to see him aiming, firing and moving than it is light show of effects. Lev Grossman's The Magicians compares trying to understand the roots of magic to the cosmology in which the world rests on the back of a turtle with further "turtles going all the way down." The further you go through the infinite sequence, the more the turtles start looking like dragons. Sometimes thinking through anime shorts seems like a similar exercise. Given the provocative nature of prior Kawamori works, I started wondering it there were implicit messages being forwarded in Shanghai Dragon along wiith the explicit praise of the power of imagination. Given that this is a short, I also had to wonder if I was drawing too many conclusions from too little evidence. The equipment and posturing of the run and gun cyborgs from the future look like unambiguous evocation of first person shooter video games. Is their need to travel back and time to borrow a child with imagination a criticism of video games/gamers? What about the fact that their AI adversaries are reminiscent of mecha anime and Kawamori;s own Macross in particular? Does the boy love's for tokusatsu shows in which a guy in a colorful suit martial art kicks colorfully dressed baddies translate into Shanghai Dragon being a tribute to that genre of shows? For that matter, if the boy really is imaginative, why is it only in the post battle celebration that his drawing turn creative? Prior to the finale, he's hungry and draws blobs of food-stuff. He sees danger and is inspired to recreate the TV shows that fascinate him...Not exactly genius originality from the kid.

"Deathtic 4"

Deathtic is the first of Genius Party's entries to put a non-traditional director at the helm. Shinji Kimura provided illustrations for Katsuhiro Otomo's picture book Hipira: The Little Vampire. He was an art director on classic anime parody Project A-ko (1986), Victorian/steamtech Steamboy (2004) and Studio 4C's Batman: Gothman Knight ("Have I Got a Story for You"), and TekkonKikreet. However, Kimura is primarily known as a background artist, with classics like Akira and Oshii's Angel's Egg (1985), as well as. other distinctive works like Tezuka's Heavy Metal-esque A Time Slip of 10000 Years: Prime Rose (1983) and Masaki Yuasa/Tatsuo Sato's Cat Soup (more on that later) Not an unbendable rule but one of the fundamental frameworks for the look of anime and manga is to put stylized, abstracted character design against a more concrete background. In this template, the viewer reads the characters as symbols, with what the character represents mentally register. The characters connect as real or at least understandable, and their images are what's remembered. You pick up the concept of Astro Boy as a child robot from his image without the need for a realistically rendered form. Yet, even if they are too complex to be remembered as explicitly as the characters, if done well, the backgrounds can be just as important for the context they provide.Kimura brings an understanding of both classic art techniques and technological tools to crafting the look of anime. From the deeply granular creation of Neo-Tokyo in Akira to the organic, lived in jumble of overbuilt, rundown sprawl of residences and commercial outlets in TekkonKinkreet's Treasure down, Kimura creates environments both studied and imaginative. Deathtic 4 is set in an animated dead alternate-verse, with pseudo Swedish language dialog. A corpsely child lies in his death bed, gasping as a heavy set monster stalks towards the room. What seemed macabre and strange proves to be anything but. The thumping beast proves to be mom, waking up Rått to get his dead body out of bed and to school. Rått has a few issues weighing his adolescent mind. Not only is he the new kid in town, he's somehow managed to find a living frog, a verboten intruder in the land of the dead. In keeping with this sort of boy's adventure, Rått finds some help from the local outcasts. In this case it's his would-be superhero classmates - spark sputtering kid " Ashe controls fire," Blaze is wrapped in a patchwork wetsuit, with a snorkel affixed to his mouth and he "manipulates water" or at least spits it, and Posse becomes a "super zombie" when he removes the paper bag from his head. This is as silly as it sounds and the short find fun ways to frame the credibility of these characters. Specifically, the class' pair of popular girls dress up in US and USSR singlets and bully the wannabes. Yet, despite being scarred and bewildered, the group decides to defy the tricycle mounted inquisition, who communicate through those cans that "moo" when turn over, as the Deathtic team helps Rått return his frog to the land of the living. In slight of hand, there are some tricks that the audience might interpret as simple that actually take a great amount of effort, skill and preparation to perform. Deathtic 4 seems like it might conform to that model. If there's any non-obvious subtext here, I haven't spotted it. Like Shanghai Dragon, the mini-adventure is entirely approachable and enjoyable. Moving as fast as it does, it's a diverting, quick experience. If you're interested in the medium, the imagery is cause to be engaged. Tim Burton is an obvious point of comparison, but there is enough spooky-world architecture and design densely packed into the short to afford Kimura an abundance of opportunity to express his original ideas. By inspecting textures and attempting to mentally reverse engineer how the images may have been constructed, there's plenty of material to think about and appreciate in the short.

"Doorbell"

Doorbell is the second of the two cases in which the anthology passes its party hat to a non-anime director. This time, it was a creator who made their name in anime's sibling medium, manga. Yoji Fukuyama's work is almost completely unavailable in North America. His Mademoiselle Mozart was recognized with the Yomiuri Drama Awards Excellence Prize in 1997 and was adapted into a stage musical. His adaptation of Don Giovanni (1992) and horror Gamura-Khan (2003), a strange mystery about a lawyer sent to look into a slimy apartment, was serialized in Morning, an anthology that has been well represented in North American manga licenses (Gon, Vagabond, Planetes). His risqué comedy Tales of the Town Uroshima told the story of an honest traveler might find himself in a village all of whose inhabitants (headless women included) make gleeful love to all comersRelevant to Doorbell, his only work available in North America is a bit of Yukiko's Spinach (2000), Frédéric Boilet's Nouvelle Manga, available via the publisher of that movement in English, Fanfare/Ponent Mon From the Nouvelle Manga manifesto At least half of Japanese comics tell stories of men and women and their everyday lives. This attachment to daily life as a theme is for me the principal reason of manga's success with a broad range of readers broad range of readers. While the universes of Franco-Belgian and American Sci-Fi or action comics almost exclusively target male teenagers, in Japan, manga's daily-life stories touch men as well as women, teenagers as well as adults. This allows the format to attract a readership larger than just otaku ; many Japanese readers are not otaku (meaning fan of manga, as one can be a stamp collector, a Formula 1 buff or a Smap groupie ) but simply curious, open-minded people who read comics as they would read novels or go to the cinema... Several other Fukuyama works available in French in that vein include Okami ga Detetika Hi (2004), released as Le Jour Du Loup by Casterman and Mister F Considered a throwback creator who worked in the gekiga mode ("dramatic pictures," as opposed to manga's "irresponsible pictures") Fukuyama's unconventional approach to manga production is described in Sharon Kinsella's Adult Manga as the work of "one of the minority of professional adult manga artists who preferred not to use assistants, but to produce their manga entirely by their own hand. In that way Fukuyama tried to maintain the strength of his artist vision and cohesion of its execution. Fukumaya's slow drawing technique and unusual graphic style were indulged by Morning editorial: 'we have no problem with his strange pictures. In no sense would Morning attempt to restrain his creativity." Doorbell is set in urban Japan, with Japanese dialog. This might be a very specific spot, but my urban recognition is poor. I once thought that an explicitly New York based movie was based in Boston... Chuck Klosterman has a bit in Killing Yourself to Live where he dialogs with an Olive Garden (or maybe another eatery franchise) waitress about time compression in dreams. It's her assertion that everyone has dreams in which years or lifetimes might pass, and that this subconscious phenomenon is learned behavior, trained by TV, movies and other forms of storytelling. Would metaphorical stories be an inverse case or did they too creep into the gray matter gears. Clearly tales in which some mental state is realized are nothing new... Twilight Zone, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Jojo's Bizarre Adventure... nobody notices me, therefore I am invisible. The concept of Doorbell is nothing new, but I'm not inclined to hold that against it. A young man goes through the circuit of his mundane life, only to find that he's been supplanted by simulacra. Except for a small girl, nobody notices him because these other selfs are in his place. This isn't Kafka or Kon. It's not Gamura-Khan or Tales of the Town Uroshima (2001). There's nothing starting or amazing in the young man's journey. The demonstration of what's happening is a function of reaction or lack thereof. Instead, the short is an exercise in manga projected onto anime. Which is to say, it's a concept work for people who like concept works; a piece for students of anime and manga to deconstruct. While it is not comprised of still images, few ideas are conveyed as anime might convey them. The bits that do fit natively into anime are subtle. At the short's conclusion, white lights strung into the tree around an apartment blink on. That's not a typical manga transition. That it stands out should be an indication of the small lines that dissect this work. The way in which Doorbell tells a story through framed expressions, the way that it cuts from bodies in motion to those faces, going back to the Kimura discussion, its abstract people in a more literal context, the anime is built around techniques that map onto an Understanding Comics breakdown of comics/manga. Like Deathtic, whether you find this interesting to look at is dependent on your fascination with the media involved.

"Limit Cycle"

Genius Party returns to the guidance of animators with Hideki Futamura's Limit Cycle. Futamura served as a key animator on Junkers Come Here (1995), a kid's movie released in North America by Bandai Entertainment, Satoshi Kon's psycho-thriller Perfect Blue (1997) and Vampire Hunter D: Bloodlust (2000). He had a major role in the AnimMatric, directing the prologue and epilogue of Koji Morimoto's Beyond, in addition to providing key animation, key animation again on Shinichiro Watanabe's Detective Story segment, and he assistant in character design, provided art design and served as assistant animation director on Mahiro Maeda's Second Renaissance.He also directed cult favorite Jojo's Bizarre Adventure (two sets of episodes in 1993 and 2001), a horror, travelogue in which colorful, basically super-heroes and villains, match wits and brutality on route to Cairo. Not specifically Futamura related, but to tie together a few threads of this discussion, Jojo's was a prominent bit of output from Studio A.P.P.P. - who worked on Project A-ko, see Shinji Kimura, who worked on Aquarion, see Shoji Kawamori, and who produced Robot Carnival, featuring Atsuko Fukushima and Studio 4C co-founder Koji Morimoto. A.P.P.P.'s North American label, Super Techno Arts indicated plans to release Sci-Fi Harry, Shadow, and the sought after Robot Carnival on DVD. However, after a very criticizable release of Jojo's Bizarre Adventure, the Super Techno Arts enterprise folded (their web presence domain is currently being forward to a slots internet gambling site). Limit Cycle proved to be the live round in the chamber of Genius Party's creative freedom. What happens when you put no limits on artists? Someone is going to produce something profoundly obtuse. Recursion is a concept in mathematics and computer science in which a function calls itself. The joke is "in order to define recursion, you must first define recursion." As that indicates, you need a based case to know when to stop. For example, the Fibonacci sequence, which is the sum of the prior two Fibonacci sequences: Fib(n) is (Fib(n-1) + Fib(n-2)). Zero and one are base cases, so when you hit them, you don't go back any further. So ... 0, 1,1,2,3,5,8,13... Without that base case, recursion is a trap that isn't escaped. Limit Cycle features pseudo-James Dean interpreting... In his monolog, he goes through associative images, symbolic interpretation, the nature of divinity and so on. I thought of Tezuka's discussion of Memories from his experimental works. And, I thought of Mel Brook's The Critic, which didn't help. I don't think that the Rebel Without a Cause's mind trip is a valid base case for a recursive short that relies on your willingness to interpret its own pondering interpretations. Narrative could supply that foundation by providing something that could be accepted without question or active consideration. If that exists here, it is an exercise in and of itself to discern. With nothing to affix to, the viewing mind is simply pulled into a sink hole. I don't have the vitriol towards Limit Cycle that some have expressed, but most who watch this short will be able to see why it's been criticized in many quarters as the most patience trying of the Genius Party collection. A little of this sort of symbolic interrogation goes a long way, see Serial Experiments Lain (1998), and Limit Cycle's 15 minutes is a lot more than a lot of viewers will have wanted to see. Without some plot or character to attach to, it doesn't invite the work required to decode what's going on. As subject as anime is to the necessities of funding and coordinated production, there are few works that are truly difficult. I neither think that Limit Cycle is inapproachable for the sake of being inapproachable nor that Futamura aimed to place his work outside the pedestrian reaches of his Jojo's Bizarre Adventures audience. It's more a stab in the direction than it is an anime equivalent of poetry or literary prose. Even if the intension isn't original and the attempt is not entirely successful, he does demonstrate that the idea is not at odds with the medium. With its jumble, juxtaposition and merger of symbols, the possibilities for imagery afforded by animation is a powerful canvas for an exploration of Limit Cycle's scope.

"Happy Machine"

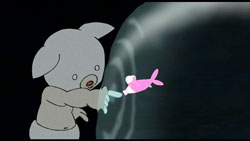

Though Masaaki Yuasa's 45, if a new guard versus old guard distinction could be made for Genius Party's contributors, and it probably can't, Yuasa would fall on the "new guard" side, with anime work dating back to 1990 rather than the 70's or 80's. (No one on this anthology is terribly young. Shinichiro Watanabe is also 45. Shoji Kawamori is 50. Yoji Fukuyama is 60.) Poll American anime fans about innovative animators, and the names to come up would likely include Mamoru Hosoda (The Girl Who Leapt Through Time), Akiyuki Shinbo (Soul Taker, Le Portrait de Petit Cossette, Starship Girl Yamamoto Yohko, Negima!?, Sayonara Zetsubo Sensei, Bakemonogatari) - whose flare is as much about the trapping and imagery as it is the animation and Masaaki Yuasa. Yuasa names Hayao Miyazaki's Castle Of Cagliostro as an anime film that inspired him in his youth. The statement has a ring of how musician might sound mentioning their first exposure to The Who or the Doors. It's evident how the energy of the not-so-gentlemanly gentleman thief roof top leaps and clock tower dives affected the animator to be. With startling abstract forms and immediately discernable freedom of motion, Yuasa brings a vibrancy to the art form, even when dealing with dire subjects.His work that North American anime watchers are mostly likely to have seen is the pot scene in episode nine of Samurai Champloo (2004). Of this noteworthy Crayon Shinchan work through the 90's, the piece that North American watchers would best recognize is the "Reggae" end credits. Ironically, the director's most notable work available in North America wasn't actually directed by Yuasa. 2001, J.C. Staff produced original video animation (OVA) adaptation of Nekojiru's (a creator with a disquiting story unto herself) manga Cat Soup was directed by Tatsuo Sato, who has done some very nice work on some forgotten sci-fi anime, including kitchen sink Evangelion period space opera Martian Successor Nadesico (1996), school dramedy meets galactic politics Shingu: Secret of the Stellar Wars (2001) and surprisingly endearing space academy series Stellvia (2003). He also has some less than sterling series to his directorial credits (the Ninja Scroll TV series). Yet, serving as scenario writer, storyboarder and animation producer, Yuasa's vision marks Cat Soup. The 34 minute odyssey is An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge meets Sanrio. Both its surreal and its mundane imagery of the jarring, creating a resonantly disturbing piece. Lamentably defunct anime distributor Central Park Media may have branded themselves with a title synonymous with terribly anime (MD Geist), but with releases like Cat Soup, they also offered anime that pushed the boundaries of the form. For other work available in North America... he did layout work on episode three of Ruin Explorers: Fam & Ihrie (1995), a largely forgotten fantasy release, key animation on episode five of infamous panty flashing OVA Aika (1997) and key animation on Isao Takahata/Studio Ghibli's water color style comic strip adaptation My Neighbors the Yamadas. OVA series Hakkenden took the like named epic novel Nanso Satomi Hakkenden and turned it into a animator showcase. Yuasa made his mark as animation director on the fourth episode of the second series (1993). Neither of his TV series have been licensed, but Kemonozume (2006) has a monstrous kissing scene that made internet rounds. (The other Yuasa TV series is 2008's Kaiba, at once a tribute to early, black and white televised anime and an abstract work that has little of the aesthetic or trappings generally associated with anime, concerning a world in which the memories of the dead are store and transfers to new bodies.) His signature piece may be Studio 4C's 2004 movie Mind Game. Directed by Masaaki Yuasa, Mind Game adapts Robin Nishi's manga of his pseudo-origin story. It receives some attention for its artistically integrated live action footage and deserves more for its fluid approach to animation. Nothing is static. From its tributes to the history of anime and relationships with pop culture to its interior avant-garde art, the shifts and vision are absolutely beautiful. Beyond the visual expression, with a very human carpe diem story that's emotionally involving, it's difficult to imagine someone not enjoying Mind Game. Mind Game has screened in North America, but never been licensed for DVD release. Its Japanese DVD featured English subtitles. Parties in the know (TekkonKinkreet director Michael Arias) have said that the subtitles were produced to promote the film for licensing, then accidentally put onto the DVD. This subtitled on the movie was posted on YouTube and reportedly the YouTube posting scuttled a deal. Happy Machine is set in some Yuasa imagined system, with pre-verbal dialog. . In college I was friends with a couple who were about to have their first kid. The woman was a psychology major, and if you were a psych major, you could get bonus points/preferential treatment if you could press gang friends and family into participating in experiments. It was my contention that when the baby was born, it would be "volunteered" for psyche experiments and that the psych experiments would be along the lines of what's presented in Happy Machine. An infant calls to his mother for milk, only to find that the provider wilts and collapses upon embrace. Shocked, the infants explores/is dropped out of its collapsing falling inhabitation and into an alien landscape populated by fire creatures, spheres of water and strange bugs. Like the Genius Party short, there's primalness in its testing of a desert landscape and search for substantial in realm of complete uncertainty. Seeing it, Happy Machine is wholly new. The description "the strange motion of strange creatures in a strange environment" sounds very Yuasa. Yet, even if you're a Yuasa watcher, it is transfixingly original. The short gets to the heart of what abstract and stylized animation is all about. While it does not look real, it evokes reality. Because of Yuasa's studied movements and expressions, there's a tactile sense to how the subject of the story feels his way through this world, and similarly a sympathy is establish with his feeling. The oddity likewise enhances the short work. A child is thrust into an environment that neither he nor you can't fully comprehend or predict. Unlike Limit Cycles, there is this child to attach to. Thinking about him, provokes an interest in interpreting the strange adventure, and because the short is engaging rather than unapproachable, it's actively perplexing. You're left wondering what it all means, and consequently, Happy Machine is the least predictable and most moving of the Genius Party shorts.

"Baby Blue"

From a North American perspective Shinichiro Watanabe is the most recognized, most anticipated name on the card. Surprisingly still occasionally mixed up with Excel Saga's (1999) comedy focused director Shinichi Watanabe, Shinichiro Watanabe carved his name into the story of anime in North America with Cowboy Bebop... a show that hit Adult Swim at the right time to be viewed by audiences from teens to forty somethings, maybe of whom watch little anime before or since.. Watanabe joined production house Sunrise where he worked on OVAs such as Ryosuke Takahashi's Armor Hunter Mellowlink (1988), Johji Manabe's Capricorn (1991) and Mobile Suit Gundam 0083: Stardust Memory (1991) as well as some TV episode supervision work on 4 panel manga adaptation Obatarian (1990) and super robot show Genki Bakuhatsu Ganbaruger (1992).In 1992, Big West commemorated the 10th anniversary of Macross with six episode OVA The Super Dimension Fortress Macross II: Lovers, Again, a sequel set 300 years in the future. The anime featured few staff members from the original Haruhiko Mikimoto (character designer), Sukehiro Tomita (scripter) and Yasunori Honda (sound director). Shoji Kawamori was among the parties who weren’t interested. This not a well remembered work prompted a change in course. Studio Nue came back with their own, sequel via 1994's four episode OVA Macross PLus. Shoji Kawamori was back. As was father of the Macross' dazzling aerial combat, Ichiro Itano - namesake of the Itano Circus. Koji Morimoto, a name that's connected all over Genius Party, whose own work doesn't show up until follow-up Genius Party Beyond, animated the neon psychodelic concerts, performed by the story's virtual idol Sharon Apple. And, Macross Plus featured Watanabe stepping up to co-direct. With its adult characters and integration with the music of Yoko Kanno (her second anime work, following Please Save My Earth, also released in 1994) the OVA laid out the pattern of Watanabe's work going forwards. In 1996, he worked under Kawamori in Sunrise's Vision of Escaflowne, where he storyboarded four episodes. He was back at Sunrise in 1998 for Cowboy Bebop. Again set to Kanno's music, the jazz and noir story of gangsters, ex-cops and feme fatales in the closing days of a sci-fi wild west era found a receptive audience in North America. If you were hoping for "the same, but different" you had to wait a while, but you were in luck with his next work. This time, it was at Manglobe, a studio formed in 2002 by Sunrise producers Shinichiro Kobayashi and Takashi Kochiyama. 2004's Samurai Champloo took its name from an Okinawan stir fry dish that literally translates to "something mixed." This time, Edo period chambara sword fighting genre work was mashed up with hip-hop music and anachronism. He worked with Studio 4°C on the AniMatrix anthology directing the Detective Story and Kid's Story segments. And it was at Studio 4°C that he launched what seems to be the latest phase of his career, producing the music for Mind Game. He took on the music producer role again for Manglobe's Michiko to Hatchin, a Brazilian set caper, directed by Sayo Yamamoto, whose previous directorial experience was the ending of Texhnolyze. Though Michiko to Hatchin has been called a "next Cowboy Bebop", the anime has not been licensed for release in North America. To throw out another bit of trivia, he was have to directed the opening of T.A.T.u. Paragate, featuring the anime incarnation of the defunct Russian pop duo. Baby Blue is set on a trip to Enoshima Island, with Japanese language dialog. If you were expecting something as frenetic as Bebop was, with like audio visual impact, you're out of luck. If you went into Genius Party expecting the unexpected, maybe you'd expect the guy behind "'The Work Which Becomes a New Genre Itself' to produce something genre-free. Something liable to attract the infuriating label "slice of life." Shou (voiced by live action actor Yuuya Yagira, Nobody Knows) is about to move out of town with his mother. Not wanting to give up on what he cares about, he decides to give up on everything. The self described good kid convinces Hazuki (live action actress Rinko Kikuchi, Brothers Bloom, Babel) to cut class with him. As he says "let's forget about tomorrow or the future." They "go somewhere..." A walk goes further and a trip to see fireworks at the beach. As the characters note "talk about clichés." There is a bit of the medium is the message here. Mark Schilling has pointed out that Baby Blue closely adheres to the tenants of seishun eiga ("youth film") - see Schilling's article on the genre here - then again, while label the label is applicable, I think it is forgivable to say that this is a not a genre story. Were it prose, it wouldn't be shelved in a special category of the book shop. It'd simply be fiction/literature. Yet, you shouldn't have to explain "guess what, anime isn't just giant robots and magical girls" to fit Baby Blue into a tradition of teen stories. Someone who watches a bit of anime and reads a bit of manga is liable to say "oh, it's this." Plenty of manga across the audience demarcations come to mind. As do the works of Matako Shinkai (Voices of a Distant Star, Place Promised in Our Earlier Days, 5cm Per Second). What I found it most reminiscent of is regrettably not available in North America, namely Studio Ghibli's Tomomi Mochizuki directed TV anime movie adaptation of Saeko Himuro's novel I Can Hear Ocean Waves, particularly due to protagonist worry of being out of sight, out of mind. It fits into that niche as a well produced instance, remarkable mostly for the people involved - Watanabe, the voice actors, Yoko Kanno. Again on the Kimura point, it effectively uses abstract character design against solidly realistic backgrounds. Given Shinkai's work on this type of story and his use of gorgeously realized backgrounds, comparisons to that animators work crop up. Baby Blue finds its place with its understanding of the tight control that an animator has on its subject. The tonal coloring, the realism of the place and its people, the nuance, it all allows the story to credibly emote. Yet, there's a major misstep. Something happens. It's no more critical to the development of the characters than any other moment, but it is very showy and it robs Baby Blue of its naturalism. It's not accidental. The short built to it all along. However, once the work begins running down hill, it may have committed itself towards sprinting into folly. I have to wonder if the experience had a Girl Who Leapt Through Time re-do, whether it would have reworked that bit.