Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

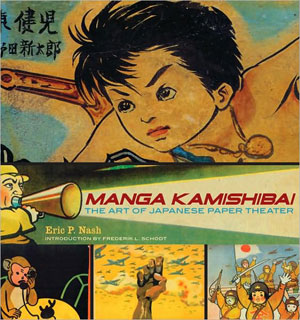

Manga Kamishibai by Eric P. Nash Released by Abrams ComicArts

Preview online here Kamishibai or "paper theatre" is a form of graphical and performance art. Primarily practiced from the 1920's to the 1950's, travelling story tellers would set up a butai (miniature wooden proscenium) and narrate stories illustrated with processions of painted cards. Though kamishibai still exists through the work of a few remaining performers, through cultural preservation efforts and as an educational tool for elementary school students, its precipitous decline since the rise of television, kamishibai has long invited the label "dead art." Manga Kamishibai introduces the medium, relates its 20th century rise and fall, and reproduces the images in a way that is gorgeous to look at and compelling to read. Collected in full color for Manga Kamishibai, the story frames remain positively arresting. With their voice and a canvas the size of what would now be a small TV, the Kamishibai performer would have to attract and enthrall an audience of children effectively enough to eke out a living from selling slightly marked up candy. Relied upon to command and hold the attention of an audience some distance away (like theatre, the performer might have to play to the back row), those painted cards served as a sort of narrative billboard sequence. Generations before Nintendo was making video games and sugary cereals were funding cartoons, critics were calling kamishibai too over stimulating for the young minds of its audience. As reproduced in Manga Kamishibai, with their exploding colors and marked by attention commanding design, the accusation does not seem entirely irrational. Around this time last year I mentioned that I adored Yokai Attack, and that the book was going to be on my holiday gift list for a number of friends/family. I did in fact follow through. As a 304 page 250 illustration coffee table/art book style hard cover, Manga Kamishibai is a bit more expensive, and I do have some reservations about the book, but I still think it’s one of the best holiday items in the anime/manga field. Definitely something to gift or ask for in the upcoming season. Manga Kamishibai opens with works that broadcast pulp sensibility with a sort of cross pollination of Eastern and Western pop culture. Eric P. Nash snaps together a chain of parallels in his opening look at Prince of Gamma, described as an "interstellar hero by way of J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan". The green suited super-hero launches into an adventure in which he "takes on a mad captain of a sea-monster-like submarine a la Jules Verne," eventually confronting a foe "more like Gumby than Captain Nemo." Also noted, "in a fascinating bit of transcultural borrowing, the [title] letters slant away from the viewer as they did in the old Flash Gordon serials, a trick picked up by George Lucas for the opening credit of Star Wars." In its next chapter, the book looks at period adventures, including the exploits of Tange Sazen, the one armed, one eyed samurai later adapted by Osamu Tezuka, who may have also inspired Tezuka's Dororo, and later tales of disfigured samurai, such as Blade of the Immortal. On this genre - jidai geki - a period drama set in feudal Japan, Nash draws attention to "the wordplay of George Lucas' jedi, who resemble medieval Japanese Knights." If this volley of reinterpretations sounds a bit like Chip Kidd's Bat-Manga or the pattern laid out in Roland Kelt's Japanamerica... in the case of the former, as illustrated in Manga Kamishibai, the Caped Crusader was worked into the medium as it tried to compete with imported American TV programming... and that in and of itself is an example of the latter. Like modern anime and manga, a significant aspect of what's fascinating about kamishibai is how it reshapes familiar concepts into startlingly different configurations. From golden age super heroes to John Ford westerns, kamishibai bear similarities to western media traditions, while reinterpreting those tradition for a different cultural context - like working Ghost in the Shell into the Matrix or Blade Runner into Bubblegum Crisis, an amalgam Batman/Joker is worked into the role of a villain for a kamishibai western. The book hits staccato notes that are both recognizably intertwined with familiar popular culture and discernably non-American. Though the image in question is from a coloring book, Betty Boop in a kimono bearing the rising sun and swastika unforgettably captures kamishibai ‘s approach to boldly reworking familiar concepts into an alien framework. After hearing Manga Kamishibai described as an art book, I was surprised by how illuminating the text proved to be. Author Eric P. Nash is a researcher and writer for the New York Times who has previously produced books on architecture and design. Looking over to my anime/manga reference shelf, I see few books on the subject matter with the attention to composition and artistic tradition. "The propeller-driven rocket bomb is about to collide with the train, highlighted in a rainbow wash of color from its lantern within the dark recess of the tunnel. Lighting from a source within the picture is more typical of Rembrandt lighting than Japanese painting. Kamishibai artists were conversant with the history of Western art, at least through art books, as well as cinema" Beyond that insight, the book shapes a compelling narrative around the history of kamishibai. Nash starts with the genre, explaining how, like manga, there were shonen (boys') and shojo (girls') stories (I recently read a bit of Jennifer Robertson's "Takarazuka: Sexual Politics and Popular Culture in Modern Japan", which refers to an Eiji Otsuka ethnographic analysis of "shoujo" and the rise of the word/concept along with consumer mass market in the post war decades - as such, I wonder if "shojo" is the best label here). After showing a few representative works and exploring kamishibai’s antecedents, the book looks at the medium's "golden age," in which the economic woes of the 30's funneled unemployed men into the field. From there, Nash introduces the manga luminaries who began in kamishibai, including Sanpai Shirato (creator of ninja epic the Legend of Kamui and significant figure in the mature manga gekiga movement), Shigeru Mizuki (horror, adventure GeGeGe no Kitaro) and Kazuo Koike (Lone Wolf and Cub). The book then hits the subject of World War II. The image under Manga Kamishibai’s Jungle Boy focused dust jacket is a tanuki (a species of animal sometimes referred to as a "racoon dog" in English) firing off a flame thrower, from a cartoonish war retelling of the myth of Momotaro, the Peach Boy. There's also propaganda with more a adult bend (portraying the sadism of Allied soldiers), or political (caricatures of Roosevelt and Churchill) or practical (air raid procedures). The post war occupation saw censorship and new influences (Disney and Warner Bros cartoons) but also new aims for the propaganda, namely American values. By the time the occupation was ending and Japan was finding a new sense of self (signified in entertainment by pro-wrestler Rikidozan, who'd triumphed over larger American opposition), televisions were being installed in public locations, and the new denki kamishibai - electric paper theatre - began usurping the role of traditional kamishibai. The most effecting part of this story might be kamishibai’s reaction to the atomic bombs. The subject was not addressed until after the occupation's censorship was lifted, but as recorded in Manga Kamishibai, works were produced to educate children who grew up after the event. These impressionistic images of young civilians wounded and walking among the dead are absolutely harrowing. Even without the intended accompanying voice of the storyteller, these haunting works stand as testaments to the power of the medium. In his commentary, Nash offers too much of a good thing, to the point where it gets irritating. Besides the ubiquitous comparisons (this looks like this Superman element, that looks like it was heavily influenced by American animators Bob Clampett and Tex Avery), the puns are nearly incessant. Following the adventures of swashbuckling, skull headed superhero Gold Bat, Nash offers caption headers "Bone Voyage," (for a panel prominently featuring the bat's billowing cape) "Cape Fear" , and Rapier Wit. Even the instructional kamishibai on building an air raid shelter features captions like "The Last Ditch." Only when looking at kamishibai that concerned victims of the atomic bombings does this sharp penned approach get pushed aside.There's a chapter in Jonathan Clements' Schoolgirl Milky Crisis labeled "Punditry" about goofs, mistaken assumptions and people not knowing stuff. One of the reprinted columns, "Explanations: The Search For Deeper Meaning," offers Clements' parody of works fascinated with and searching for the history of manga. He aims to mirror the style in an origin story for western comics, full of associative leaps from cave paintings to the Bayeux tapestry to harry potter fan fic. Recollections of this essay underscored my discomfort with Manga Kamishibai. With Manga Kamishibai's jumps between the history of the art form and a more recognizable pop culture framework, I wonder if the book projects a certainty that cannot be fully supported. The frequent comparisons make the subject more approachable, and place it into a larger artistic context, but also draw in plenty of implied influences. I'm not second guessing from an informed position. To the extent that I do know the subject, I don't believe that the book is explicitly wrong. I do think that it is implicitly a little shaky. Manga Kamishibai presents an artistic history that is less complicated than maybe it should be. A lineage is outlined from the pictorial histories and fables of Buddhist emaki (illustrated scrolls) to kibyoshi from the Edo period -1603-1868- (illustrated text, printed in a comic book like format) to kamishibai and modern manga. Line these media up next to each other and it does look like an evolution as one form is adapted into the next. I've never read Adam Kern's Manga From the Floating World: Comicbook Culture and the Kibyoshi of Edo, a book that is named in Manga Kamishibai's bibliography. I have heard Kern talk about the subject. His presentation details a host of parallels between manga and kibyoshi, from graphical touch points, to business to public reception. Then, he stated that though there is the appearance that kibyoshi became manga, the real relationship is probably not that simple. It's not wrong to give the history from emaki to kibyoshi to kamishibai to manga, or to point out the striking similarities between the characters represented in kamishibai and western media. However, pointing out similarities is not entirely intellectually satisfying. While I don't believe that Manga Kamishibai lands itself into any trouble, it would have been welcome to see the book present some complications in those comparisons or to present a case in which apparent relationships were misleading. The final chapter, Across the Mangaverse is more apt to bring this ambivalence to the forefront for many fans of anime and manga. For example, there is a statement: "Though he was too young to be influenced by kamishibai, Satoshi Kon started in the 1980s as a manga-ka and went on to create the anime series Paranoia Agent and the acclaimed anime Millennium Actress - a kaleidoscopic recap of Japanese film history, including the years in frozen Manchuria. Marvel Comic's Iron Man and Spider-Man have been retrofitted to have a more Japanese sensibilities by Madhouse Studios, a renowned Tokyo-based animation company. As a man protected by a metal suit, Iron Man appeals to fans of anime featuring mechanized characters like Mobile Fighter G Gundam and Appleseed." Nothing in that statement is incorrect. If naming Spider-Man rather than Wolverine in the Marvel/Madhouse slate might sound off, remember that this reflects the announced plans prior to last summer's San Diego Comic Con. Yet, as an anime fan, these narratives go against the grain. True, in part it is disorienting because it is an outsiders view of familiar, often spoken about subjects. Yet, at the same time, I'm not entirely convinced of how accurately the passage captures the spirit of its addressed subjects. The general anime fan's narrative for Satoshi Kon's career is that he started on psycho-thriller Perfect Blue, and followed that with a series of movies, most recently Paprika, with a deviation into televised anime via Paranoia Agent. This ignores the fact that his post-education entrance into the field began as work with Akira creator Katsuhiro Otomo on manga, before contributing to Otomo's anime work, with script and art direction on the Magnetic Rose section of theatrical animated anthology Memories and design on OVA Roujin Z. Manga Kamishibai's references to Paranoia Agent, then Millennium Actress fits the book's structure, especially given Millennium Actress' journey along with the evolution of media tradition. However, the implied progression from Paranoia Agent (2004) to Millennium Actress (2001) is misleading. From its inception with Osamu Tezuka's work on Astro Boy, televised anime and theatrical anime have had distinct production models. As such, it is essential to emphasize that Kon has primarily worked in theatrical anime, with Paranoia Agent representing a shift of his approach into, what for him is, different territory. Less relevant to the nature of the art and more geek-nitpicky, the phrase "mechanized characters like Mobile Fighter G Gundam and Appleseed" is perplexing to a long time anime watcher. There is no way to express this without sounding egregiously geeky, but the reference points make the statement akin to saying "American space operas like Phantom Menace and Star Gate SG1." 1994's Mobile Fighter G Gundam is the first "alternate universe" Gundam series, meaning that it broke from the time line establish by the original Mobile Suit Gundam and tweaked the premise of the sci-fi war story. Whereas the original Gundam tried to present the titular robots as quasi-realistic military equipment, G Gundam recast as them as colorful super powered totems in a fighting tournament. As a divisive outlier in the popular franchise, few scenarios crop up in which "G Gundam" would be the first mecha series to come to mind. Back in the 90's a subset of mecha fans admired the robotic "landmates" that Ghost in the Shell creator Masamune Shirow designed for Appleseed. Now, when Appleseed is remembered, it's for its CG animation. I'd pin a low estimate on how many anime fans remember its commando heroine Deunan Knute and her bunny-headed cyborg partner Briareos. I'd pin an even lower estimate on how many self-described mecha anime fans would put Appleseed on their top 10 list. When Manga Kamishibai reaches the section tying the preceding material to modern anime and manga, what was said reinforce an impression that I had had with the book. It was not that what was being said was wrong. I just was not sure how right it was. Is Manga Kamishibai worthy of attention even if a scholar or familiar audience might "tut tut" some of its points? Despite the misgivings I have concerning the style and content of its commentary, I'd still unequivocally recommend Manga Kamishibai. As I said with Bat-Manga, I'm thrilled by the notion of preserving a medium with created with intension of immediately arresting the attention of an audience. That this medium is caught up in the tangled history of eastern and western traditions influencing each other makes it even more fascinating. However, given dazzling images of the painted kamishibai, you don't need to predisposed to the subject to be entranced by Manga Kamishibai.

Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit Volume 2 by Motoro Mase Released by Viz Manga

Note the cover of Ikigami. A tormented guy holds up a card bearing a time stamped photograph to his forehead. In the background, a ghostly face screams in anguish. This is Ikigami distilled to a single image; its proclivity to hit tragedy on the nose written on the tin. Manga is a medium that trades in expressiveness. Survey the covers of a selection of manga. The majority will feature characters broadcasting some immediately discernable emotion. Consequently, it might not be fair to hold Ikigami's obvious pathos against it. The problem is, I don't trust this manga's sincerity. I don't expect a standard genre manga to truly reflect the sentiments of its creator. As long as period action manga Ruruoni Kenshin offers involving sword-resolved conflicts, I don't care about Nobuhiro Watsuki's analysis of the Meiji Restitution or his thoughts on the moral implications of violence. Ikigami presents tragic tales in speculative sociology. It is a social engineering high concept blown out into a manga comprised of one off stories... The Lottery: The Manga... A Modest Proposal: The Manga... To join two very obvious comparisons, Battle Royale meets 1984. This is territory that I'd hope was populated by works that genuinely had something to say. Yet, two volumes in, I'm not convinced that Ikigami, is putting much thought behind the handwringing. Ikigami is set in an alternative version of present Japan in which, during their school admission immunizations shots, one in 1,000 children is injected with a nanocapsule that will kill the recipient at a predetermined time between the ages of 18 and 24. The "Ikigami" of the title is the label for the people whose macabre role is to deliver a message to alert the doomed that they will die within 24 hours. This involved process, known as The National Welfare Act aims to have every citizen growing up wondering if, and when, they will die. In theory, the existential uncertainty reinforces the citizens’ value for life and, following from that, increases social productivity. Those unconvinced of the merits of the Social Welfare Act are labeled "social miscreants," send to re-education camps, and, if still opposed, injected with lethal nanocapsules. The character contemplatively frowning on the cover is Fujimoto, a young man employed as an ikigami. The volume opens with Fujimoto's girlfriend confronting him about his work as they sit in a cafe. "It's not like in itself is wrong... I mean your work is essential to our country... but... I never know when you are going to be called in... and after a delivery, you want to talk... I can't live with that." "You can't understand?! I crush someone's life... and then I don't feel talkative?!!" "That's what I'm saying! You end up crushing me too!!" Where upon Fujimoto, perhaps not too sensibly, admonishes his girlfriend, mentioning that she could be called out as a social miscreant, reminding her that it is the duty of all citizen to inform on thought criminals. Having this conversation in public may not have been advisable, as the people nearby mutter "pss, a social miscreant? her? is she crazy?" As in the previous volume, Fujimoto proves to be the bridge for two distinct stories of death notice recipients: "The Pure Love Drug" - concerning the put upon (and physically and emotionally abused) girlfriend of a driven, drug addicted would-be director, and "The Night He Left for War" about a nursing home attendant and his relationship with an elderly woman who'd given up on life. While the focus of the volume is this pair of stories, Ikigami also continues to carve out a path for Fujimoto's metastory. Reputedly, the drug taken by the would-be director can extend the life of someone whose heart stopped for an hour. "By the way, I've heard these pills can prolong your life... is that true?" Where upon the (foreign looking) dealer proceeds to explains exactly how the supposed life extension works. It'd be shocking if that never factored into a further development in the manga. Ikigami ran in the anthology Big Comic Spirits, home to Crying Freeman, Maison Ikkoku, and Uzumaki. It isn't for an audience that is particularly young. Hence the "Explicit Content" warning label, which is in no way needed for this volume. Given the age of its audience, the manga's directness is aggravating. Painting a direly objectionable picture of the Social Welfare action, then demonstrating its beneficial results, the manga is achieving emotional confusion. However, chasing that effect is not the same as fostering intellectual ambiguity. With large panels framing faces that are weeping, dismayed or driven, the emotional signposts erected along the stories unmistakable. To the same result, nothing of consequence is left unaddressed by the dialog and captions. Ikigami will raise provocative issues, such as drug use, physical abuse or even sacrifice paralleling service in World War II. Then, it will jump to directly mapping those complicated issues onto concrete elements of the story in which they're raised, with little time or space left for consideration. That explicitness discourages reading more from the stories than the emotional impact. Nor does the manga seem concerned with more than that sorrow or bittersweet sting. Beyond the meta-unease, the Social Welfare Act conceit seems to serve little more than as reason for the lives of 18-24 year olds to be conclusively resolved. Other than Fujimoto who dwells with it day to day, the lives of the subjects seem not to be impacted before the arrival of the death notice. For example, "The Pure Love Drug" gives a reason why the character is manically set on becoming a director which has nothing to do with the premise of Ikigami, with little evidence the he considered the defining differences in his speculative alt-society before they directly intruded into his life via his girlfriend's death sentence.

Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service Volume 9 written by Eiji Otsuka illustrated by Housui Yamazaki Released by Dark Horse Manga

As the title might indicate, the pitch for Kurosagi Corpse Deliver Service seemed to be that the manga was going to showcase realistically rendered cadavers in a panoply of circumstances. However, around the second volume, it struck me that the manga's writer Eiji Otsuka had something to say. This wasn't simply the product of skimming urban myths and hot button current affairs to construct modern ghost stories. There's a distinctive, liberal arts educated authorial voice to The Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service. It's interested in esoteric facts. It's interested in history. It's conscious of the implications of those facts and history. After reading more of the manga and more about anthropologist and cultural critic Otsuka, I feel that it's not hyperbole to call Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service one of the smartest horror series, regardless of origin. I'd point to the manga's unreserved curiosity and spendthrift utilization of story concepts to back that claim. My favorite example of this approach occurs in volumes seven, where one particular story draws from celebrity branding, plastic surgery, the mouse that had a human ear grown on its back and the lore of jinmenso (a supernatural tumor with a human face) for an episode twisted with multiple revenge plots. Driven by real intellect and informed opinion, volume nine of Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service finds Otsuka fitting an examination of the social ecology around otaku and the legacy of World War II into horror stories. This genre has long addressed prickly issues metaphorically, but watching Otsuka fit his theses into the structure of horror is almost poetic. The Japanese serialization of Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service has changed publications three times as the periodicals have shuttered, repackaged or relaunched. Given volume eight's attention to establishing (or reestablishing as the case might be) the fundamental premise of the series and the identity of its characters, I strongly suspect that the volume caught Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service sticking one of those dismounts. It managed some effecting moments in some familiar horror scenarios, but what it appeared to be doing seemed more out of necessity than inspiration. Volume nine is back on firmer ground, and back with its unique MO of synthesizing diverse bits of history, politics, sociology and esoteric facts horror ghost stories. Because Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service is one of my favorite manga, it pains me to admit that I forgot that I had read volume 9. I went through it, shelved it for a while, and when I picked it up to read ahead of this review, I was disappointed to note that rather than new material, it was something that I'd already read. The issue is not that Kurosagi's stories are forgettable. It's that they are constructed with the aim of exploring diverse subjects through the horror anthology format rather than driving an ongoing narrative. Its character are a crew of over-educated, under employed Buddhist college grads whose lack of job prospects and un-marketable skill sets led them to the unprofitable business of delivering dead bodies to where they need to be. The characters do matter. They are well constructed and their backgrounds do have a bearing on the course of the manga. This volume in particular reveals significant background information about Keiko Makino - the loligoth embalmer and Yuji Yata - who claims he channels an alien intelligence through the sock puppet worn on his left hand. While there is a meta-mystery relating to the characters, along the lines of the X-Files mythology, it has thus far been more background than a driving force of momentum. Manga writer Otsuka is fifty one years old, which makes him slightly younger than the creators who were close to Japan's student protest movements at their height, like Mamoru Oshii or Katsuhiro Otomo. His background includes academic study in anthropology, women's folklore, human sacrifice and post-war manga. When it comes to the academic discussion of die-hard fan otaku, Otsuka is on a tier with Gainax co-founder turned intellectual (and diet book author) Toshio Okada and celebrated pop artistic/Superflat founder Takashi Murakami. Unlike manga that exists in a vacuum or trades in concepts divorced from reality, Otsuka grounds his the work in thoroughly considered extrapolation of true issues. Unlike Murakami, whose work speaks about rather than to otaku, and rather than Okada, who has distanced himself from anime creation and creators, Otsuka has remained in the trenches. Looking at otaku and World War II, the subject matter of volume nine is clearly in Otsuka's wheelhouse. He isn't trailblazing in his approach to the subject matter either, with stories involving or driven by stock characters such as an egocentric starlet, corrupt politician or duplicitous research partner. The first of the volume's stories exemplifies the manga's use of conventional moving pieces, such as the above mentioned starlet/idol is harassed by creepy, persistently reappearing doll. Otsuka's interest in mechanics and obscure curiosities can be seen in the detailed procedure used to create possessed dolls and the recreation of a shrine for unwanted toys. Otsuka puts on his culture critic hat and breaks out the otaku-ologists scalpels as he deconstructs the geek/object of geek affection dynamic. As editor Carl Horn says in his legendary end notes "Eiji Otsuka's feelings about otaku are, shall we say, nuanced." Rather than comfortably simple recriminations, Otsuka delves the convoluted feedback channels between extroverted, fame seeking idols and introverted, obsessed fanatics. The next story, The Grape Colored Experience plays to Otsuka's own geek interests. Like the grand ear mouse/tumor/branding episode, this one is a titan of alloyed ideas... a headless horseman, the Susumu Tachi optical camouflage cloak, voyerourism, Mamoru Oshii (a great doppelganger appearance) and associated pop culture representations. There's a great Tarantino-esque thread around an argument as to whether the invisibility camo was inspired by Ghost in the Shell or Oh! invisible man (oh! toumeiningen), suggesting Otsuka's own fascination with the subjects. After a slightly below par volume eight, volume nine is back to the hyper-informed horror synthesis of ideas that has made Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service a favorite. What originally seemed to rely on gross out spectacles has continually proven to be a remarkably smart take on spooky standards.

For more commentary see the AICN Anime MySpace.