Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

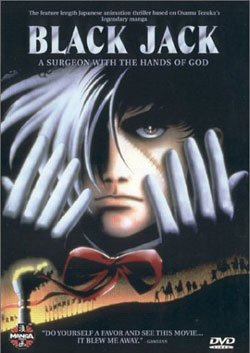

Win a Copy of the Black Jack anime movie

One of the most exciting manga ("manga," as in Japanese comics) releases of late has been Vertical's publication of Osamu Tezuka's classic scalpel for hire medical adventure Black Jack. The third volume of this series was just released on January 20, 2009, with volume four listed for March 17th of the year. Though Osamu Tezuka is recognized as an innovator in the field of modern manga, who established the template for the medium, his works also stand alone as unequaled in many ways. Watching him test a set of ethics through the parable of an unlicensed surgeon is both powerful and fascinating. And, as I've said before no genre fan should pass up a chance to read Tezuka's Black Jack. Chiefly a medical adventure, drawing from Tezuka's own background as a licensed physician, the manga takes a detailed, scientific approach to both trauma surgery and medical oddities, but at the same time, it pulls from everything from robotics to the tradition that would be called "J-Horror" if rendered in live action (eye transplants that repeat visions from a previous owner, jinmenso tumors with a human face) and spins its own morality tales. Black Jack was an extremely popular manga series in Japan, and like many manga with a dedicated following, Black Jack inspired anime. Many of these adaptations were directed by the great Osamu Dezaki, and, one of the highlights of this anime is the movie Black Jack: A Surgeon With The Hands Of God. Released in North America by Manga Entertainment ("Manga," as in the anime distributor), the movie is currently available on DVD. Manga.com has been gracious enough to work with AICN to offer five readers a copy of the outstanding movie. To win, answer the trivia question: Black Jack’s sidekick Pinoko is... A a parasitic twin. B a tumor known as a Teratoma. C a construct created by Black Jack. D All Of the Above. And fill out the form here (don't send an e-mail my the column e-mail address or the stand contest one) The contest ends on 2/23 so make sure you get your answer in before then. See rules for details

To Win a Copy of the Black Jack movie, fill out the form here

Anime Spotlight: Black Jack: A Surgeon With The Hands Of God Released by Manga Entertainment

I wouldn't say that everyone will love the Black Jack anime movie. There are certainly people who I consider to have reasonable taste in anime who dislike it, and while I don't share their opinion, I can see where they're coming from. As a medical thriller, it needs to stay at least partially grounded in reality. For example, what it shows happening to the human body has to stay within the threshold of suspension of disbelief. The movie is helped by the prominent facial features and attention to anatomy in Akio Sugino's character design, which reinforces the impression of looking at real, specific people. It starts in a fairly credible manner. Action opens in the midst of the Atlantis Summer Olympics. There's an infrared view of a pole vaulter setting a record, cut to a fully realized context shot, with a crowd full of people exactingly rendered. From this point of mild exaggeration, it goes into a torch song, James Bond opening, and from there, the anime movie explodes beyond good sense in every aspect. It combines the script license of a summer blockbuster, with hyper-expressiveness. Our hero is bribed, blackmailed and forced into solving the mystery behind why a group of people exceeded the limitations of human abilities, breaking athletic records and creating unimagined art, then, began dying in grotesque ways, with rapidly deteriorating bodies. And, as might be expected, there's a conspiracy and compromised motives behind the disease and the effort to solve it. As the situation plays out, there's plenty that's laughable, form a cameo by Osamu Tezuka's Don Dracula, to the world renowned surgeon "Doctor Michigan from Kent State," to the scene where the G.I Joe branch of Doctors Without Borders executes an armed overthrow of a megacorporation’s hospital. Yet, I'd still insist that Black Jack: A Surgeon With The Hands Of God is a fascinating movie that should be seen by anyone with even mild interest in anime. While the sum of its parts might add up to an acutely melodramatic action movie, surveying the elements that went into it is quite breath taking. As such, time spent deconstructing Black Jack is as rewarding as it can be for any anime. Black Jack: A Surgeon With The Hands Of God is by no means a new film. It was created in 1996, with a North American DVD release in 2001. Yet, here's a reason to think of it as something retroactively buzz worthy. The Ain't It Cool News audience get very excited about pairings of favored directors and famous genre characters - Spielberg on Tintin - del Toro on Hellboy - Nolan on Batman - Kevin Smith (at one point) on Green Hornet - Guy Ritchie on Sherlock Holmes. One of these pairings is Osamu Dezaki on Black Jack, which proves to be a partnership that yields all of the complexities that you'd hope for in seeing an idiosyncratic director tackle a venerable character. If you've never heard the name, Dezaki is a John Woo of anime directing, with a varied career ranging from sports stories, to historical fiction to space opera. If nothing else, his take on the two fisted surgeon is certainly unforgettable. While Astro Boy is "God of Manga" Osamu Tezuka's most popular character, it's been suggested by experts, such as Jason Thompson, that Black Jack was the innovators most popular manga. As he debuts in the manga, Black Jack is immediately a striking figure. Exiting a plane, the wind dramatically lifts up his black overcoat, black ribbon tie and shock of white that stands out in the front of his black hair. As the manga closes in on his face, determined eyes glare from a scar crossed face. The MO of this unlicensed surgeon is that he'll travel nearly anywhere and solve nearly any medical condition, provided that his demands, including an exorbitant payment, are met. Tezuka's Black Jack manga was full of danger, violence, medical oddities, and stomach turning - up close views of surgeries, but they were also succinct parables defined by Tezuka's style of story telling. As dark and grisly as the stories might be, they use Tezuka's abstract, classical cartoon inspired stylization, and feature his mannerisms. "The Painting is Dead!" follows a young artist exposed to radiation in a nuclear weapons test. He asks Black Jack to prolong his life long enough to produce a painting that does justice to the reality of what he witnessed. As effecting as the story is, it's full of Tezuka's almost cute caricatures and invasions by his tension breaking sense of humor. Black Jack is planning what can be done for the terribly burned victim, and for a panel, the man's head is replaced by one of Tezuka's gag pig-nosed gourd. There's an ironic contrast between Tezuka's introduction of Black Jack and how Dezaki first introduces him into the movie. Rather than a dramatic imposing figure, the movie's Black Jack appears with his back turned to the camera, sitting at a desk in a small seaside cottage, quietly packing his instruments. Yet, even if the characterization is faithful to Tezuka's, his role has been projected into a more adult, noir world. Especially in light of his interactions with a beautiful dangerous woman, and the deadly intrigue surrounding international incident, the unrelenting, hyper-competent, marble figure of Black Jack is cast as more a medical James Bond or Golgo 13, with occasional glimpses of a soul, than a Tezuka player. Put in dark colors and illuminated by the fluorescents of hospitals, neon cities or dimly lit restaurants, this is Black Jack literally in a different, more dramatic light. These presentation differences are starkly emphasized by Black Jack's side kick, Pinoko. This child bodied assistant considers herself to be eighteen, and Black Jack's wife, while the doctor more reasonably regards her as a daughter. The relationship is still creepy, spawning David Welsh's well phrased question Wrong, but how wrong?. In the manga, you can sort of put aside the notion that Pinoko is a person and appreciate her as a lively cartoon entity. When Pinoko is depicted in flesh tones for the anime, and the solemn dangerous looking scarred man in black has this cherubic kid hanging off him, the disquieting nature of the pairing is really staring you in the face. From the North American perspective, Osamu Dezaki is not one of the better known anime directors. Older and hard core fans probably know the name, but there are also probably at least a good dozen directors who are more likely to be known by the general body of anime fans. Yet, it is a significant name to know. He was an episode director in the original Astro Boy. He left Tezuka's Mushi Pro to become one of the founders of Madhouse (Ninja Scroll, Paprika, Black Lagoon) and during the course of the 70's, he helmed a number of classics, which would become quintessential templates for their genres. There was the boxing tragedy Tomorrow's Joe and the girl's tennis title Aim for the Ace! (inspiration for plenty of sports anime, and mecha sci-fi Gunbuster). He did several entries in the World Masterpiece Theater omnibus (home to the like of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, including Nobody's Boy: Remi Treasure Island. Then, he would leave the decade with famed shoujo anime The Rose of Versailles, about a girl raised by her father as a boy to inherit his position as palace guard in the court of Marie Antoinette. The 80's saw Osamu Dezaki work on a number of male audience aimed works including more Tomorrow's Joe, The Mighty Orbots, Golgo 13 :The Professional, Space Adventure Cobra, and, for North American viewers, Bionic Six. And he's continued to work in the medium with 97's Hakugei: The Legend of Moby Dick, 2005's The Snow Queen, Hamtaro: The Movie, the Air movie, the Clannad movie and now an adaptation of the early eleventh century the Tale of Genji. A lot of those 70's classics were highly melodramatic. I challenge you not to laugh at the earnestness and rain soaked intense glances in Aim the Ace! trailer (if that doesn't do the trick, how about hazing). The Black Jack movie is unabashedly packed with pitched set pieces. Everyone's making grand pronouncements in accordance with their type. In a small, dark room, with rain beating on the window, Black Jack confronts the woman he's been working for and against. She's hunched over, clenching a glass of wine. "It's a death drug! Don't you feel any sense of responsibility? You'll never be forgiven!" This might as well be "You can't handle the truth!" It's such a stylized version of a tortured confrontation that it seems like the director should have his fingers crossed; that he's going to play it as a joke. Parody may have encroached so deeply into the associative links that melodrama may have become indistinguishable from goofing on the material. I can't see Aim for the Ace! without thinking of a sculpted haired innocent shoujo heroine walking onto the panel of Usamaru Furuya's savaging of youth culture in Short Cuts (not to mention Gunbuster) or watch on of Black Jack's tense confrontations without finding unintentional humor. Yet, I don't think an ironic viewing is the most rewarding way to approach Black Jack. The titular character is an unwavering medical knight errant, defined by his adherence to a set of ethics more than by his identity or history. As such, this self-serious, melodramatic approach suits the character. I'm inclined to think that many viewers will not buy into it, but it is still possible to appreciate how the movie develops and maintains that tone. In Anime Classics Zettai! Brian Camp calls Dezaki the "most baroque stylist in anime." His experiments in the medium have not always worked (see the CG helicopter in Golgo 13, but his willingness to try new models for relating a narrative through anime has made Dezaki the kind of creator who has given anime its vitality. Whether it's shaving a head in preparation for brain surgery or piecing together a jigsaw puzzle, there's a strong sense of presence and interaction in the Black Jack movie. People on screen really seem to be moving in such a way that they're actually making things happen. Dezaki is putting together what will seem like a real, physical world and not just the short hand stand-in for one. He follows through with the precise way in which he realizes that world. In a globe hopping adventure, he's going from the Olympics, to Black Jack's humble retreat, to Germany, to New York, to Hawaii, to the Mediterranean, to Serbia. The way in which the visual elements like color scheme and lighting is adapted to each environment is amazing. Black Jack sits at a candle lit dinner, then hurries to a dark hall to use a pay phone; in the background, through an art deco window, a blimp with a neon pattern illuminating its side passes by. This is extravagant without being distracting, and serves the purposes of a movie that intends to look like a big budget blockbuster. Even in the current model of film, where CG has muddied the distinction between what can be done in a live action movie and what can be done in an animate one, the quantity and scale of the sets in Black Jack beat live action thrillers at their own game. The flip side to that attention to reality is the movie's symbolism. These are the cases where concrete representations of the world are twisted to reflect the characters' perception. Paprika's Satashi Kon is famous for it, but Dezaki is pretty damn good about using his own visual vocabulary for expressing himself too. You spy in on a conversation through a ventilation grate at the top of a room. Then, the screen will be split into four horizontally aligned spaces by slanted lines, each zooming out further from a close-up on the speaker's eye. The funhouse disorientation is exaggerated, as the slices are realigned and repopulated by a view of the conversation's other party, then again, back to the original speaker. They crop up late, generally during the climax, but Dezaki's pastel freeze frame "Postcard Memories" do appear as well. As much as any director, Dezaki is comfortable exercising the flexibility of anime. Black Jack's script loudly clangs around like a rattling subway car, and I don't think that it's going to move many viewers, but even the ropiest bits of the plot are amazing to look at. With the intensity of the visible heat and pumping blood vessels on screen as Black Jack operates, or a still shot of Black Jack coughing blood into a glowing field, the movie is full of amazing images. North American anime fans often go back to anime for the next fix of a popular genre or story type: the next relationship comedy with some cipher guy and a host of exotic girls, the next high concept action, and so on. Yet if you look at the classic anime movies that commanded the attention of North American audiences, like Akira, or recent examples, like Paprika, classic TV series that commanded the attention of North American audiences, like Star Blazers, or more recent examples, like Fullmetal Alchemist, those anime offered intriguing characters and a presentation that offered a new experience. Again, I don't think that people will love the Black Jack movie, but they should see it. Anyone interested in anime should own some work by Osamu Dezaki. He's too influential and too interesting not to be part of an anime collection. The Black Jack movie is certainly a bold, well funded, well animated, full expressed example of his work and as such, it's a great anime DVD to own.

Manga Spotlight: Black Jack Volume 3 By Osamu Tezuka Released by Vertical, Inc. A preview can be read here

Osamu Tezuka's Black Jack was serialized from 1973 in the anthology Shonen Champion. This wasn't written as young children's manga, but it wasn't seinen or gekiga for adults either. And yet, on its own terms, the manga is capable of speaking to a modern, older English speaking audience. The third collection of Black Jack's back to back stories "Dingoes" and "Shrinking" exemplifies how the manga both conforms to and cofounds the expectations of many of those potential readers. Dingoes is what might be expected from a medical adventure manga. It starts with a very cartoonish, cartoon history of the introduction of dogs into Australia, complete with a Looney Tunes-esque pack chasing down an emu, then feasting on drum sticks. From there, the story cuts to Black Jack driving through dusty fields towards the farm of an acquaintance. Tezuka drew from many models of storytelling in constructing his manga, and the sequence in which Black Jack is confronted by the emptiness of the farm house he encounters is positively cinematic. With walls boxing him in, there's an impression that the only sounds to be heard are those made by Black Jack himself as he "tromps" through empty rooms. Then Black Jack finds bodies marked by mysterious red spots. He hears a small plane and leaves the house to investigate, only to find himself thrust into a brief North by Northwest homage. Wandering alone for days in the vast fields, Black Jack soon finds himself infected. Testing a stool sample, he discovers intestinal mucosa blood cells and a segment of some organism. So, he decides that he needs to operate... on himself...in the middle of a remote Australian farm. From there, Tezuka dips into his own background as a licensed physician for a close-up, detailed operation. And dingoes smell the blood... and things get violent. This is rather ridiculous, but it's a species of ridiculousness with which anyone who watches television medical drama should be accustomed. It's the exploits of a genius, tough as hell maverick doctor, chronicled by an artist who knows how to maximize the effectiveness of his medium, and is willing to let things get interesting. While Dingoes was keeping the subject exotic and exciting, Tezuka puts on his fabulist hat for Shrinking. A peer shows Black Jack a pair of shrunken heads, to which Black Jack responds "Hmmm. I've never laid eyes on one before, but shrunken heads are local custom, no?" The other doctor du jour then brings out the preserved body of a full mained lion, only it's the size of a house cat. It appears that the African country which Black Jack is visiting is being ravaged by drought and famine, but also by a mysterious decease that shrinks the afflicted to 1/3 of their size before becoming fatal. Tezuka is explicit about the fact that the story is developing a metaphor. Yet, this isn't even the most cartoonish fantasy that Tezuka intends to be taken seriously. "The Robin and the Boy" features a bird delivering spare change to Black Jack's door in order to pay for a boy's operation. So, a guy in the outback cutting himself open to pull a parasite out of his organs sounds bad-ass, but why don't shrinking lions and Mr. Blue Bird paying for the poor child's surgery constitute kiddie fantasy to be enjoyed ironically, if at all? The reason Black Jack still should be of interest to an adult reader is that the invented diseases and anthropomorphized animals aren't the marks of an author talking down to his audience. Instead, it's the freedom that Tezuka affords himself in constructing scenarios with which to pursue his dialog on the nature of medicine. While this occasionally leads into heart warming territory, Tezuka's active engagement with the subject is not about being sentimental or comforting. At its core, Black Jack is Tezuka examining medical ethics and the role of doctors in the world. Like many Tezuka ideas, it's complex and a more than a bit at odds with itself. While Black Jack places unbound value on human life, he is also critical of the woe caused by the series to itself and to its environment to the point of being antisocial, if not outright misanthropic. Tezuka has an avatar for his philosophy in Black Jack, and that surrogate is going to be tested over and over again, in order to see how his world view holds up under calls for justification, contrary ideas, and set backs. If you're churning out a chapter of manga a week, it must be tempting to do what you need to do in order to keep the readers engaged, and shade in the underlying themes as an after thought. In Black Jack's home anthology, Weekly Shonen Champion, I don't think Go Nagai was up all night trying to ensure a coherent subtext to Cutey Honey; the same applies to Keisuke Itagaki in Baki the Grappler. Rather than simply use themes as justifications for his stories, Osamu Tezuka discernibly took seriously the philosophy behind what he wrote. As such, he employed complex means of interacting with the underlying ideas. In his more epic ventures, he turned around the idea, twisting it into an intricate knot. Thinking about the convolutions employed by Osamu Tezuka, 8th century Japan set part four of his Phoenix cycle, Karma, comes to mind. After his birth, Gao's father raced up a steep incline to thank the mountain spirits for a strong baby, but, in a twist of fate fell to his death and left Gao scarred, less one eye and one arm. Taunted by his peers, Gao's rage builds until it boils over into murder. One of his first encounters is with a sculptor named Akanemaru, whose kindness toward Gao is rewarded when Gao maims the sculptor's arm. The paths of the Gao and Akanemaru take parallel courses, occasionally overlooking each other, and converging again at the story's conclusion. Gao continues his life as a murderer and bandit until sorrow leads to his capture and subsequent release into the guidance of a wizen one armed monk. The monk hopes to calm Gao's spirit, but instead Gao finds an outlet for his hate, and the frustration of his country's people in grotesque sculptures. Akanemaru is likewise led back to sculpture by a monk, but finds himself on the guiding edge of the intersection between spirituality as politics with who see Buddhism as a tool to unify and subjugate the masses. Black Jack isn't one of Tezuka's serpentine narratives, along the lines of his Phoenix, Three Adolfs or Ode to Kirihito. It's comprised of short, punchy fables. In contrast to the novelistic form shown by most of the manga released in North America, each chapter of Black Jack is its own story. Occasionally, a piece will offer some insight into Black Jack's history. More rarely, a story will introduce a re-occurring character. Earlier, we got "daughter"/"wife"/assistant Pinoko. Volume three introduces an antithesis to Black Jack's morality with the euthanasist Doctor Kiriko. Yet, for the most part, Black Jack is a formed person, who's mind and relationships have already been defined. Personalities with which the reader is familiar reoccur from story to story, but rather than persistent characters with developing relationships, they're new instances of the templates from Tezuka's star system of designs readapted for the roles in specific Black Jack stories. From the stand point of long term story telling, none of these characters are developing; not even Black Jack himself. Popular manga often features dynamic, or at least progressing, lead characters. If the lead character is largely static, their relationship with a cast of personalities serve as a hook for the manga. The guy gets strong, and becomes the best... the girl gets the guy... the protagonist surpasses the antagonist... rivals turn to join the hero. Look... our time spent with these characters mattered! Eschewing (or, for the most part, pre-dating) this proposition may seem like a liability for Black Jack. Instead, the stand alone nature of Black Jack stories frees the manga's creativity. Without regard for the long term impact or transitional logistics of how and why the character gets to his various stopping off points, Tezuka has free rein to invent whatever test he can imagine for his titular doctor. Carried out over 25 or so pages, and actively engaged with its ideology, the Black Jack chapters have the keenly honed edge of sharp short stories.