Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

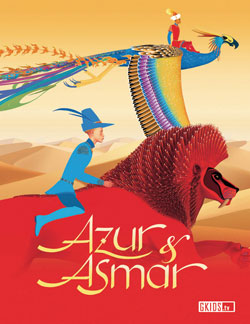

Azur and Asmar

Based on English language audio preview DVD To be screened by New York International Children's Film At the IFC Center in NYC, starting Friday, October 17 Currently scheduled screen times include Sat & Sun, Oct 18 & 19, 11am - IFC Center, 323 6th Ave (at West 3rd) Sat, Nov 29, 11am, 2pm - Symphony Space, 2537 Broadway (at 95th) IN ENGLISH - FOR AGES 6 TO ADULT For tickets see GKIDS.tv A limited theatrical release across America is also potentially in the works. Weinstein Company has scheduled a DVD release for February 2009

Pan's Labyrinth was a useful reminder of the power of fairy tales. Presumably, if you are reading AICN, you're a genre fan. And, presumably, if you're a genre fan, you were already willing to credit the majestic potential of fantastic fables. The arrival of Pan's Labyrinth was akin to the difference between recognizing that stove tops heat up and sticking your hand on a burner... like talking up Westerns in 1991, then being able to point to Unforgiven in 1992. Like Pan's Labyrinth, Azur and Asmar is what a cinematic fairy tale should be... an enchanting journey into the unique vision of its creator with an imprint of that creator's moral world view. Like Pan's Labyrinth, Azur and Asmar inventively draws from a fascinating array of sources. While Pan's Labyrinth director Guillermo del Toro found inspiration from places as varied as Lewis Carroll, Stan Winstone, Francisco Goya and Catholicism, Azur and Asmar director Michel Ocelot looked to Europe's elves and Arabia's djinns, Jean Fouquet's work and North African architecture. It's unfortunate that you only get one opportunity to watch a Michel Ocelot movie for the first time. While animation followers would have known of him as the president of the Association international du film d'animation (ASIFA) from 1994 to 2000, English speaking enthusiasts generally discovered his work when they were bowled over by 1998's Kirikou and the Sorceress. Born in France and raised as a child in Guinea before moving back to Anjou as a teen, it's tempting to reductively surmise that Ocelot's background suggested the spirit of globalism that has given his work its distinctive beauty. In the case of Kirikou and the Sorceress, Ocelot recounted the legend of an African folk hero who could speak and reason from the moment of birth in a vibrant manner, reminiscent of Henri Rousseau's paintings. In Azur and Asmar, he projects the antagonism of Eastern and Western culture onto the rivalry between brothers within a fable. Kirikou and the Sorceress and Azur and Asmar are the antithesis of a growing equivalence between animated and live action film. With CG effects the possibility of animation has been brought into live action. With improvements in 3D modeling, the concreteness of live action has been brought into animation. While animated works like Wall E successfully reaffirm animation as its own medium, with a unique way of expressing personality and the relationship between characters and their world, that contrasts a prominent tendency towards emphasizing verbal wit over visual imagination. As in boldly distinctive animated films like Chomet's Triplets of Bellville, Arias' Tekkonkinkreet or Satrapi's Persepolis, Ocelot recasts the world in image of his story. Here, living figurines act out a classic journey of questing, exile and triumph across continents and cultures. Caucasian featured Azur and Semitic featured Asmar are the clever, brave heroes of fairy tales, rivals and brothers. The pair grew up in the European estate of Azur's father, where Asmar's biological mother, Jenane, served as Azur's wet nurse, then nanny. As Azur grew up, his strict father separated the boys, then expelled Asmar and Jenane. Though Azur matured into the handsome, poised man that his father had hope to mold, Azur remained enthralled by Jenane's stories of a Djinn Fairy princess, separated from the world by magical gates and guarded by beasts such as the Crimson Lion. Fate and fabulists tend not to make undertakings of that magnitude particularly easy or strait forward, and soon en route, Azur finds himself shipwrecked in a land of people speaking Asmar's half-remembered language. Faced with mobs who view his blue eyes as a sign of evil, Azur endeavors to find his way to the Djinn Fairy under the guise of a blind beggar. Few true fairy tales, and fewer meaningful ones, are without pointed arguments. Azur and Asmar is less evasive than many concerning where its sympathies lie. Overt "multiculturalism" doesn't have strictly positive connotations for all audiences. Personally, I'll enthusiastically read Chinua Achebe or watch Deepa Mehta, but, for me, the notion of multiculturalism as its own intension has the ring of a dull reading assignment. "You might be drawn to Philip Roth and Cormac McCarthy, but shouldn't you endeavor to expand your horizons?" Like anything, espousing progressive ideals can be done artfully or it can be done gracelessly. You can get the arresting humanism of a Tezuka manga, or you can get cloying "It's a Small World After All." In this case, Ocelot offers a narrative that is inclusive and interested rather than reductive or critical, in which virtues and faults find equal distribution regardless of location or culture. With an artist's eye, Ocelot establishes vivid contrasts. An observation of the mud, rocky wastes, bigots and thieves makes the sages, gardens and mosaics more glorious. He then imbues Azur and Asmar with the movie's vital qualities by surveying the globe and history, then embracing different motifs for capturing the human, natural and fantastic worlds. Early on, Jenane tells the children of fairy caves and terrible beasts, and the movie is set onto a progression to build to that spectacle. Along the way, if there is a spice market, a patch of wild flowers or an ornate object, Azur and Asmar takes the opportunity to marvel at the sight. Employing a masterful command of color and composition, Ocelot crafts a gorgeous work of animation that pulls from the artistic movements of Azur's and Asmar's heritages. Characters like a precocious princess, bristling at being cloistered and overlooked are plainly emblematic, but, because those qualities are arrived at honestly, morality and personality are winningly grafted. The final scene of the movie goes into Shakespearian comedy mode, with a few corrections that are adorable and right for the vision of the movie, but arbitrary within the film's story. That's the exception. While the movie's lessons are unmistakable, they are also heartfelt expressions of its characters. When a frantic Jenane proclaims that there is no possible way that she could know if a red blood stain was evidence of Azur or Asmar's injury, it works on dramatic and didactic levels. In many cases, bland, concrete 3D cgi animated work miss an obvious point. Different media are often at their best when showcasing qualities emphasizing what is native and particular to the given medium. Stage or film can offer an actor embodying a role. Poetry can expose a masterfully crafted arrangement of words. Animation can recreate motion and landscape in such a way as to bear the imprint of the animator. Every expression and object becomes an instrument for relating the animator's ideas. As demonstrated by classics, from Disney to the Toei movies that gave Hayao Miyazaki his start, this flexibility to illuminate or caricature aspects of the story and weave in fantastic elements makes animation an ideal medium for fairytales. Watching Ocelot artfully present a unique vision for his account of these fables is a pure delight.