Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

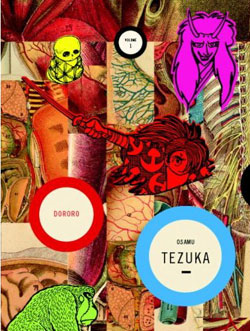

Manga Spotlight: Dororo Volume 1 By Osamu Tezuka To be released by Vertical April 29, 2008

In Dororo, "God of Manga", creator of Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion, Osamu Tezuka ventures into the territory of the dark and strange. For a genre fan, Dororo has been the classic manga to hold out hopes of seeing translated for English release. It's the pioneer of the manga tradition wading neck deep into the mire of freakish swordsmen, ghouls and historical messiness: Kurosawa and Leone meets Romero. For this manga, Tezuka fits the haunting world of the yokai into his view of the human condition. While the 1967 manga is a boys' adventure, starring a sort of samurai cyborg, a physically ravaged swordsman in the tradition of the one armed Tange Sazen, or comparable to the heroes of later manga Blade of the Immortal, Kurogane and even Berserk, hunting down the 48 demons who robbed him of a normal body, the manga is not just a warrior with swords for arms cutting through bandits and harrowing boogiemen and not just the tragedy of a flawed hero. Tezuka offers one of his deeply felt dialectics on the human will to survive versus all of the ambitions than endanger that. His sense of irony is sure to appeal to modern, adult reader, and that disparity between the expected and the reality starts with the title of the manga. "Dororo," named for a childish mispronunciation of dorobo, "thief" is actually the side kick or fool of the manga. While Dororo remains a resolutely human force, in each of his victories, the swordsman Hyakkimaru trades a piece of the artificial body that makes him an effective warrior for a more fallible, human piece, and yet, at the same time, he loses some of his humanity in the experience. Fostered by his manga self-portraits in which Tezuka depicted himself as a little man defined by a large, round nose, thick framed glasses and a barret , the notion of Tezuka as a creator merges with this cartoon image, leaving the impression of a genius that fits into fiction rather than reality. As Frederik Schodt's Astro Boy Essays illustrates, Tekuza's work was key to establishing the breadth and depth of the topics covered in manga, but he was also competitive. Whether it was Disney's movies or the experimental movement of mature gekiga, if Tekuza saw someone else doing something interesting or popular, he wanted to try his hands at it. In one of his forth-wall breaking gags, Tezuka has the eponymous Dororo react to the central back-story of the manga by proclaiming "Shigeru Mizuki should here it!" In the same way that early, prominent shoujo manga can be seen as a reaction to Tezuka's Princess Knight, Dororo can be seen as a reaction to Shigeru Mizuki's GeGeGe no Kitaro. GeGeGe no Kitaro played to boys' fascination with monsters and the grotesque. Mizuki's manga was the story of a boy with a bag of tricks for solving various problems, except the boy was Kitaro, a child born in a graveyard, who had a connection to the ghost world. Stranger still, in place of his missing left eye, his father resided, shaped like an eyeball in the socket. And Kitaro's helpers, bag of tricks were all representatives of Japan's yokai world of folklore creatures: bakeneko ghost cats, flat cotton strip Ittan-momen, sandals and an umbrella from the tsukumogami (objects that come to life on their 100th birthday). Yokai are a perfect subject for boys', shonen manga. The west has its share of interesting mythical creatures, whether it is harpies, minotaur and cyclops of Greek mythology, the unicorns, the skiapods, the horned men and so on. Yet, the yokai offer a wonderfully strange funhouse mirror view of the natural world and the human mind. On one hand, they are the stuff of cautionary tales, the things that lurk in spider holes waiting to consume people who break ancient rules of etiquette. On the other, give a child some paper and pencil, and what they draw might as well look like this host of rolling, disembodied heads, toad people, wandering skeletons and so on. Tezuka works these creatures into a story set in the Sengoku or "period of warring states" that ran from the 15th century through the institution of the Tokugawa shogunate in the 17th. In the absence of a strong central government, Japan fragmented into contesting daimyo ruled domains. Exacerbating the human suffering, the 15th century also saw famine and earth quakes hit Japan. In Dororo, this doesn't just represent the past or offer a pre-modern platform for people to attack each other with swords. The landscape in the manga is comparable to Tezuka's images of late World War II in his manga Adolf. It is an almost apocalyptic scramble where communities of people are frequently subjugated or devastated. Whether it is bandits, samurai, peasants or wanderers, no party is romanticized. As grave as the histories of Hyakkimaru and Dororo might be, Tezuka sets them in a context where they are not categorically exceptional. Early in Hyakkimaru's wanderings, he is taken to the shell of a temple where the child survivors of a battle linger in the remains of their village. In light of their plight, Hyakkimaru, who has been given a powerful, if artificial body, seems fortunate. One of the era's local lords convinced a priest to bring him to the Hall of Hell. The lord prostrated himself below the temple's demonic statues and promised the demons any prize that they wish for in exchange for victory in battle and rule over the land. While making this offer, a baby mouse fell onto the floor of the temple. Inspired, the lord promised the body of his soon to be child. So, on a bright morning, with birds chirping and people busy and content in their work, the lord's wife gave birth to a child with 48 body parts taken by the demons. Noting that the child lacked eyes, nose, ears, limbs, and so on, the lord was overjoyed to find that the deal had been consummated. The most that his wife could do for her son was put the newborn into a basket and let it float down the nearby river. This basket was found by a doctor who had been by the river gathering herbs. As the child grew, the doctor became shocked by the child's super human will to live, which was so strong that the child was able to find food without the help of any normal senses and even speak into the doctor's mind. The doctor went on to create a prosthetic body for the child, who he named Hyakkimaru, Hundred Demon Boy. Though they were happy, the boy was marked by the demon world and his presence began drawing ghouls to the doctor's hut. Shape shifters came before the doctor as patients, hoping to ensnare him. Slobbering nasties began showing up in pots and closets. The rafters became crowded with rock throwing imps. Eventually, the doctor prepared Hyakkimaru by fitting a pair of famouse swords into his arms and set him out into the world. After new, cruel experiences with the harshness of the outside world, Hyakkimaru began hunting the 48 demons who possessed his missing body parts and met up with Dororo, an indomitable young thief with a tragic past. Osamu Tezuka is brilliant at establishing a cinematic quality to his manga. He's brilliant at cartooning motion. Neither furious sword fights nor inventive creatures are Tezuka specialty. With Looney Tunes whirled charges and monsters that aren't quite as exotic as some visions of yokai, Dororo often does not compare to a modern action manga or to the work of a manga artist who specializes in horror and the supernatural. "Compensate" isn't the right word. Tezuka is not utilizing the same approach as shonen action manga artist or a horror manga artist. But, ultimately, the manner in which he presents the story is as compelling as that of any manga. Starting with Hyakkimaru's father's bargain, in telling this story Tezuka suggests that the reader is privy to something lost or hidden. The view of Hyakkimaru's father entering the Hall of Hell seems to be tracking the man's footsteps from the shadows, before sneaking to a perch over the shoulders of the demonic statues to view the candle lit scene below. When Hyakkimaru leads Dororo and a group of villagers to a forest clearing where a creature with a head larger than its torso is sitting, grinning idiotically and ring a hand bell, the startling effect of seeing something that looks like it was meant to be hidden from the human world, in a context that should have been hidden adds an eeriness to the manga's supernatural world. Tezuka's great mind for manga is evident in how he constructs the physical landscape of a scene, and then panel by panel, determines the angle by which the action should be depicted. As if he were producing a movie, he builds a set then storyboards how his script will be captured. In what he depicts and how he depicts it, Tezuka is keenly aware of the freedom afforded by the medium in which he is working. Hyakkimaru enters the story in classic ronin fashion: the wind is kicking up so much debris from an old battlefield that only the bones and armor strewn ground can be seen. A blurry figure makes its way closer from the horizon, and by the time Hyakkimaru is in view, he's in the midst of a marauder ambush. The closed circle of attackers before the fight, and the disorder of the bodies afterward capture the danger and the chaos of the confrontation. Then, when Hyakkimaru precedes to walk into a ghost town with a phantom pair of sandals following at his heels, the mix of martial wariness and paranoia that track the cuts to Hyakkimaru's face and eyes is an effecting mix of Leone and Hitchcock. When a mass of swamp muck advances on a fight and begins consuming the combatants, it isn't Tezuka's design for a swamp thing that makes the encounter harrowing. What's harrowing is the impression established by image to image progression of the manga, of this oozing corruption that consumes humans to the bone, unstoppably moving towards the protagonists. The intended audience for Dororo was not quite as young as that of Astro Boy, but it did run in Weekly Shonen Sunday, home of Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro, Mitsuteru Yokoyama's Giant Robo, Shotaro Ishinomori's Cyborg 009, much of the Rumiko Takashi shonen including Ranma 1/2, Inu Yasha and Urusei Yatsura, as well as recent titles Yakitate!! Japan, Zatch Bell, and The Law of Ueki. Yet, Tezuka's command of the form and his use of the form as a scalpel for dissecting the human condition makes his younger-audience works appealing and provocative for older readers. Tezuka's body of work is marked by a balance between popular entertainment and addressing how he perceives the world. Astro Boy directly dealt with the war in Viet Nam. A year after starting Astro Boy, Tezuka adapted Crime in Punishment using characters that looked like they were out of a Fleischer cartoon. There's a contradictory admiration for and disgust with humanity in Tezuka's works, including those for younger audiences. In Astro Boy, Doctor Tenma created Astro to replace his deceased son. When Astro failed to grow up, Tenma rejected his creation, selling Astro to an abusive circus master. After torment in a robot circus Astro was rescued by the kindly Professor Ochanomizu . In this thumbnail, there is Tenma's blinding love for his son, his unconscionable rejection of his Astro, the cruel commercialized treatment of Astro under the circus master Ham Egg (a perennial heel in the Tezuka re-used troupe of characters), and the altruistic Ochanomizu's championing of Astro. Tezuka's compassionate humanism and his criticism for humanity, and even pessimism regarding the human condition, coexist in his story. In the case of Dororo, the balance of what is justifiable in the action of the manga's subjects defies conventional storytelling algebra. No action simply moves the morality ledger in the direction of salvation or damnation. This is a grim, perpetually compromised world. There are bandits who hold the manga's sympathies who kill prisoner samurai, for the crimes committed by all samurai across the land, as this particular group samurai beg for their lives. In the darkest moments of Phoenix, Tezuka celebrated humanity's tenacious hold on life, but here in Dororo, the acts of the peasants plagued by war and famine is viewed with some shame. If Hyakkimaru kills a man who has been corrupted into a blood thirsty killer, can it be called a good thing if that man's sister is weeping next to his corpse? Even Hyakkimaru's mission to hunt down the yokai whose posses his missing body parts is questionable. Part of the manga's irony is that the yokai are a factor in the world's problems, they do cause problems, they do kill and cause suffering, but they are not the chief cause of human misery, or even Hyakkimaru's misery. Hyakkimaru's condition leaves him no choice but to venture into the world. Yet, venturing out, the sights he must witness and the action he must take chip away at the humanity that he's fighting for. Watching Tezuka advance his characters into what looks to be an inexorable conundrum (it is inexorable, Tezuka did not bring Dororo to a conclusion) is fascinating, especially given that he's working within the framework of a shonen adventure. Dororo stands as a classic that showcases Osamu Tezuka's unique approach to manga and to the world. For genre fans, both of these illuminate a story of swordsmen and spirit and spirits in a compelling way.