Hey, everyone. "Moriarty" here with some Rumblings From The Lab.

Holy crap. Where did this COME from?!

I was contacted a little while ago by Douglas TenNapel. I’ll be honest... I didn’t know the name at first. He introduced himself as the creator of EARTHWORM JIM, though, and that was at least something I recognized. I remember back in 1993, when I was dating a girl who was working for Universal’s marketing department, and they had just signed up the EARTHWORM JIM property and they were all “very excited” about it. I think I heard that phrase about 5,637 times in regards to the property. I remember seeing a game, a cartoon, some other merchandising, but I never really read it or watched it or played it. Same way with THE NEVERHOOD, SKULL MONKEYS, and BOOMBOTS, three fairly surreal games from DreamWorks Interactive, all utilizing claymation. I knew of them, but never really picked them up.

One look at his website reveals a guy who works a lot, a hypercreative artist whose work is, I think, quite beautiful. His illustrations and, especially, his paintings are emotive and hyperstylized and for me evoke thoughts of classic illustrators and cartoonists.

The reason he got in touch with me was because he just finished a new graphic novel that Top Shelf is publishing. He wanted to send it to me. Sounded interesting enough, especially from his description of it. He said it was something he’d originally optioned to Columbia Pictures, but after two years, the rights reverted to him, and he decided that he was going to have to draw the project as a comic instead of getting it produced as a film. People just didn’t get it.

And there’s no doubt. It’s weird. It’s incredibly, absolutely, no shit weird. It’s also very funny, profoundly sweet and heartfelt, touching in a strange way, and serious about concepts like faith and family without being in any way preachy or corny. It’s a tightrope act of possible tonal clashes, but it somehow manages to move with consistent grace and ease. I’d even go so far as to say that this particlar book is one of those knock-it-out-of-the-ballpark personal masterpieces. I don’t use this word lightly, and I don’t often write reviews for comics because I’m not moved to. There’s just too much on my plate. But CREATURE TECH provoked me. It dared me. It was so compulsively readable, so beautiful on page after page after page, that I read it three times in a day. All 208 pages of it. And I’ve read it a number of times since.

Simply put, CREATURE TECH is the best American animated film since THE IRON GIANT. Yes, better than TOY STORY 2. Better than SHREK. Better than anything from any studio. I know... it’s a graphic novel... but when you read this thing, there’s no doubt what it is. It’s a movie that just happens to be in print. It’s the complete storyboard, every frame, of something that would blow people’s minds. It’s incredibly entertaining, first and foremost. No matter how strange it gets, no matter how daring a moment TenNapel goes for, the thing always entertains. Every panel is worth looking at. Every character is worth spending time with.

The book begins with images of eels. Giant eels. In outer space. Sounds bizarre, and it is, but it’s also quite lovely. Beautiful, even.

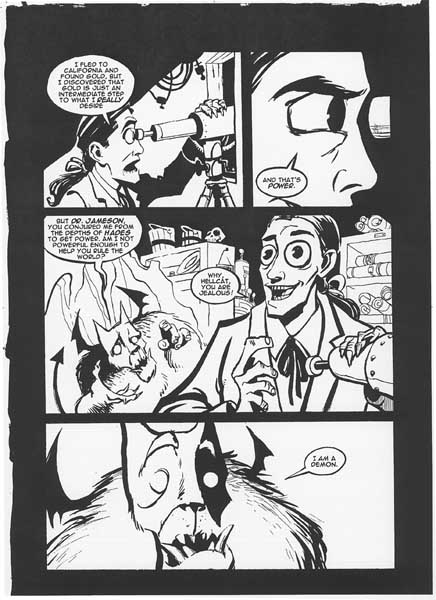

It’s 1854, and in Moccasin Creek, California, twisted scientist Dr. Jameson is working with Hellcat, a demonic entity that he conjured up, trading one of his hands for the ability to do so. I have immediate affection for any villian who proclaims, “My peers claimed that the giant space eel did not exist! They said I was crazy! Now that I have spent my fortune on a laboratory in the wilderness, swapped hands with a demon, and called a giant space eel to Earth, PERHAPS they won’t think I am so crazy after all!!!”

That’s my kind of guy.

His plan is to call a space eel close enough to Earth to be able to prove their existence to the rest of the scientific community. Thanks to the fumbling of Hellcat, though, the space eel slams into Moccasin Creek, killing Jameson and Hellcat and literally burying the eel from the force of the impact.

From there, we flash forward to meet Dr. Michael Ong. We learn how he wanted to follow his father into a religious calling. At 14, he took his first semester of Greek at a local seminary. At 15, though, he reversed completely. He learned that his father was a scientist first, before he became a pastor, and Ong’s sense of youthful rebellion kicks in. He leaves the spiritual life behind. He leaves Turlock, California at 16, already out of high school. At 19, he wins a Nobel Prize. He moves to LA, a celebrity of sorts. His brilliance attracts the attention of the US government, though, and finds himself seduced into doing the last thing he wants to: going back to Turlock.

Seems that Turlock is where Research Technical Institute is located, a low-profile high-secrecy facility that is responsible for cataloguing all of the unexplained things the government has come across and stored up. Many locals get hired to help maintain the place, but ultimately, it’s Ong who has to run the place that gets nicknamed “Creature Tech.”

Dr. Ong isn’t trusted by most of the locals. And that’s fine by him. He doesn’t like or trust them, either. He resents being back in the town, and the longer he stays, the more it weighs on him. He’s gotten so jaded that he doesn’t even see real wonders when they appear before him anymore, as we see in a hysterical early sequence at a local man’s MUSEUM OF THE WEIRD & PAWN SHOP, where a real alien mummy gets laughed off by Ong as a fake. Ong’s distracted by the man’s granddaughter, Katie, a whisper of a girl with an amblyopic eye and an atrophied hand who, despite that, fascinates him. He’s drawn to her.

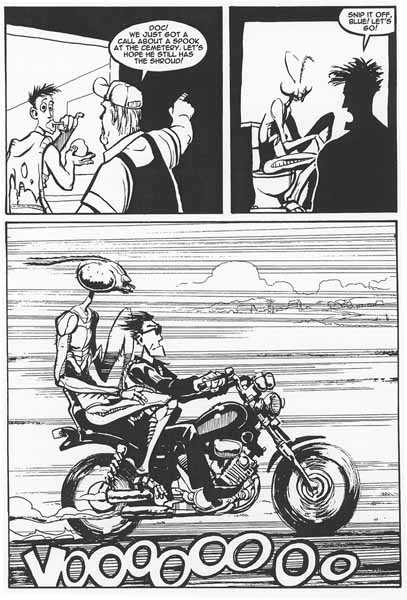

Ong’s contract specifies that he has to work his way through each and every crate stored at Creature Tech before he’s allowed to close up shop and relocate. That’s 763 items he’s got to examine and classify, many of which are terrifically dangerous and insane. He’s working on them in waves, and upon opening a crate that contains the Shroud of Turin, he sets off a series of events that changes his entire life. The ghost of Dr. Jameson steals the shroud and releases a Slugbeast that sports a parasite it wears almost like an armored breastplate. In the surprisingly horrific action scene that follows, the Slugbeast ends up dead, and Dr. Ong ends up with the parasite attached to him, having replaced his heart. It can’t be removed without killing him, and Ong has to resign himself to the idea of life with his new passenger attached, and he also has to retrieve the Shroud with the help of his new security chief, a Mantid named Blue, genetically engineered from a chunk of amberlith.

Really... it’s not confusing when you’re reading it. TenNapel believes in this world completely, the way W.D. Richter and Earl Mac Rauch completely believed in the world of Buckaroo Banzai. In cases like this, any sort of wild flight of fancy seems appropriate and normal, and the book’s inner logic is so consistent, so tonally correct, that you just accept it and go along for the ride. I did, anyway, and I can’t imagine resisting the charms of this book.

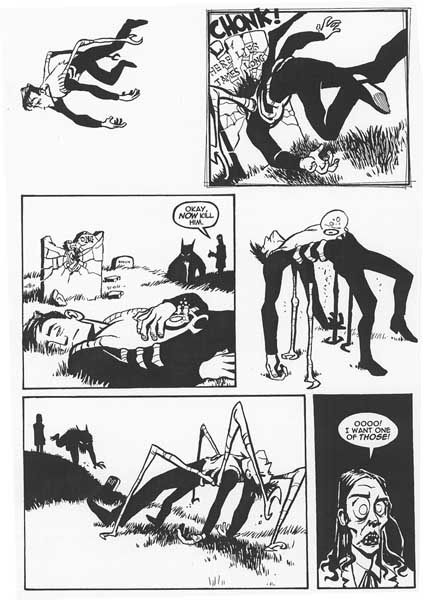

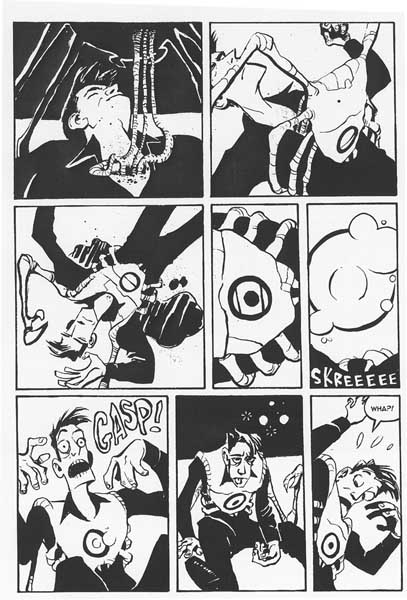

The way the action sequences are designed, they’re all kinetic and inventive, with Ong gradually realizing that the parasite, his symbiote, is actually making him into something more than he used to be, something better. It learns and is able to retrain his body, taking over certain functions completely. It can fight, it can flee, it can climb and swing and a dozen other things. This comes in quite handy as we learn that Jameson’s got the ability to turn any cat into a demon with a simple incantation. The first battle is nearly disastrous for Ong, and it’s only the quick actions of the symbiote that save him.

I’m impressed by TenNapel’s ability to invoke various emotions with grace and ease, shifting gear dramatically but never jarring the reader. He can write a sweet, strange love story that intercuts perfectly with a tale about a father and son and the tensions between them as well as the story of a freaked-out killer grasshopper’s unlikely discovery of his place in the world, and he can punctuate all of this with hilariously surreal moments like the eye-popping short, sweet life of the Meatman on pages 89 and 90.

Take the fine line he walks with his depiction of the Shroud Of Turin. He uses it as an artifact of power, the magical device that powers many of the story’s more outlandish moments. Turns out the blood on the shroud raises the dead. One of the most striking images is when Jameson falls hundreds of feet from the sky, wrapped in the Shroud, knowing he’ll die when he hits, and knowing he’ll get up and walk away afterwards. But TenNapel also brings in some smart and heartfelt debate about the value of something like the Shroud on a spiritual level. Dr. Ong is sure his father will be thrilled to learn that the Shroud is real, since this scientifically proves that his faith is right. Instead, his father is almost disappointed. He calls it a short cut and says that faith has no value when it’s given something concrete, something that “proves” God’s existence. Being able to write both sides of the idea so well is what marks TenNapel as a voice worth listening to. This isn’t just fun; it’s got something to say, something real and lasting and moral. Like THE IRON GIANT, this is a book that makes sure the action all counts for something. There are some amazing sequences as Jameson unleashes an army of demons on Turlock and Ong tries to stop them, but it’s a quiet panel on page 143, a single still image, that packs the hardest punch, as we come face to face with the depth of our feelings for these characters, as oddball as they are. And the absolutely barkingly funny pages that immediately follow elevate the material even further, as we get a glimpse at just how rich and free TenNapel’s imagination really is. And then we double back and around page 163, TenNapel takes us somewhere I would have never anticipated and does something of such incredible courage that I would recommend the book for the unusual grace of that leap alone.

The ending accelerates with all the controlled chaos of the best work of Zemeckis & Gale, and there’s a series of reunions (one of which brought real tears to my eyes, one of which is creepy and unpleasant) that close things out. TenNapel gives his “villains” motivations that we can’t help but understand, and the way he finally brings things to a close is aching, emotional. We close on an image just like the one we began with, a giant eel in space again, and now it means something totally different. Now it counts. Now it’s so beautiful you almost have to look away.

Half of me hopes to see this movie someday soon.

Half of me knows that no movie will ever be as rich and daring as TenNapel’s book.

All of me urges you to seek this out, immediately, and enjoy it for what it is: an original, emotional powerhouse that should speak to anyone who approaches it with an open mind, and an announcement that TenNapel is someone to watch closely from this point forward.

"Moriarty" out.